Superstorm [suːpər ˈstɔrm]

Here is a short list of major news organizations referring to Sandy as a “superstorm”: The L.A. Times, CBS News, Time, The Guardian, Business Insider, the Toronto Star, and the Wall Street Journal.

Here’s what Professor Alan Blumberg, professor of ocean engineering at the Stevens Institute of Technology and director of its Center for Maritime Systems, says a “superstorm” is: “It’s a media invention. There’s no real meteorological term called ‘superstorm.'”

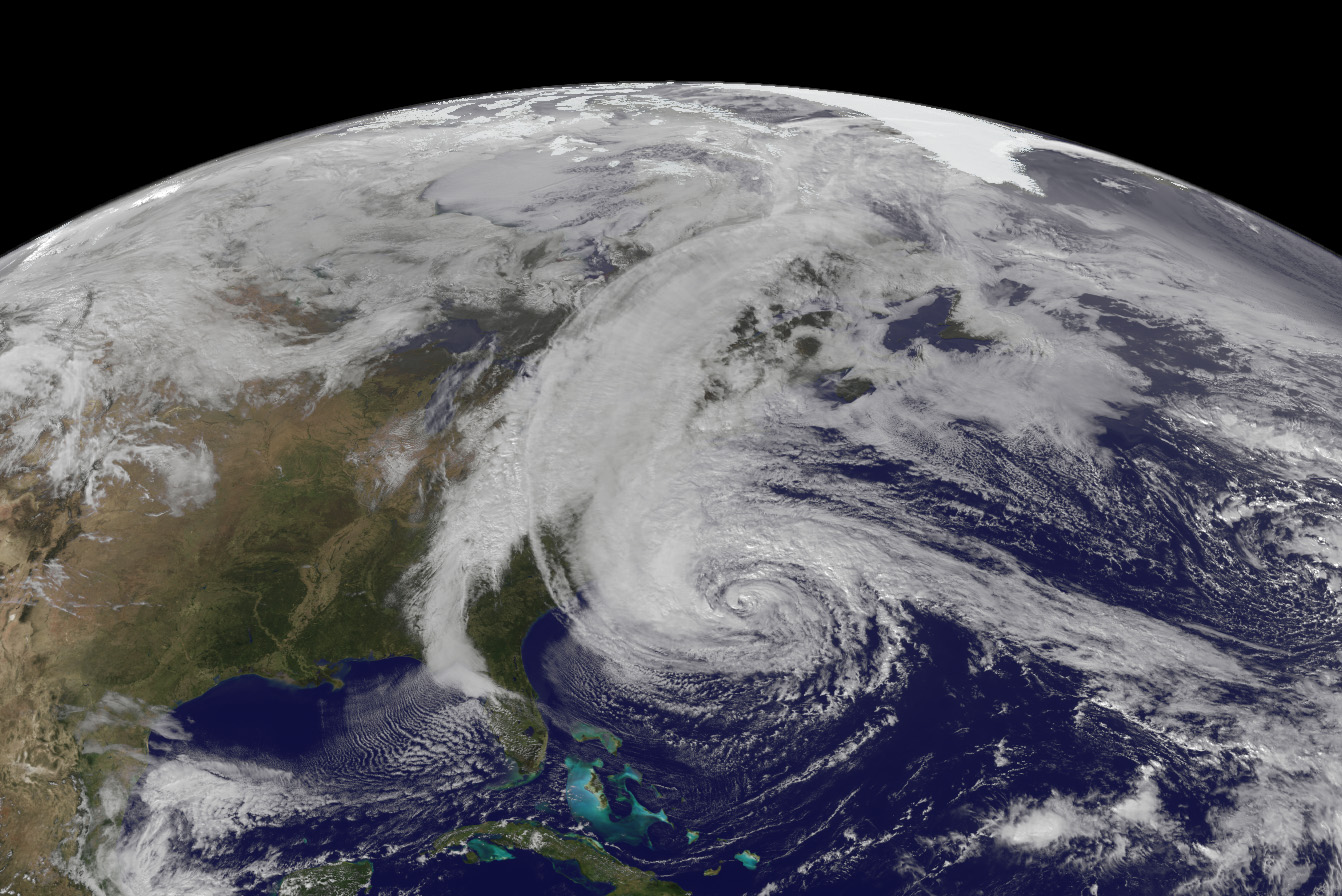

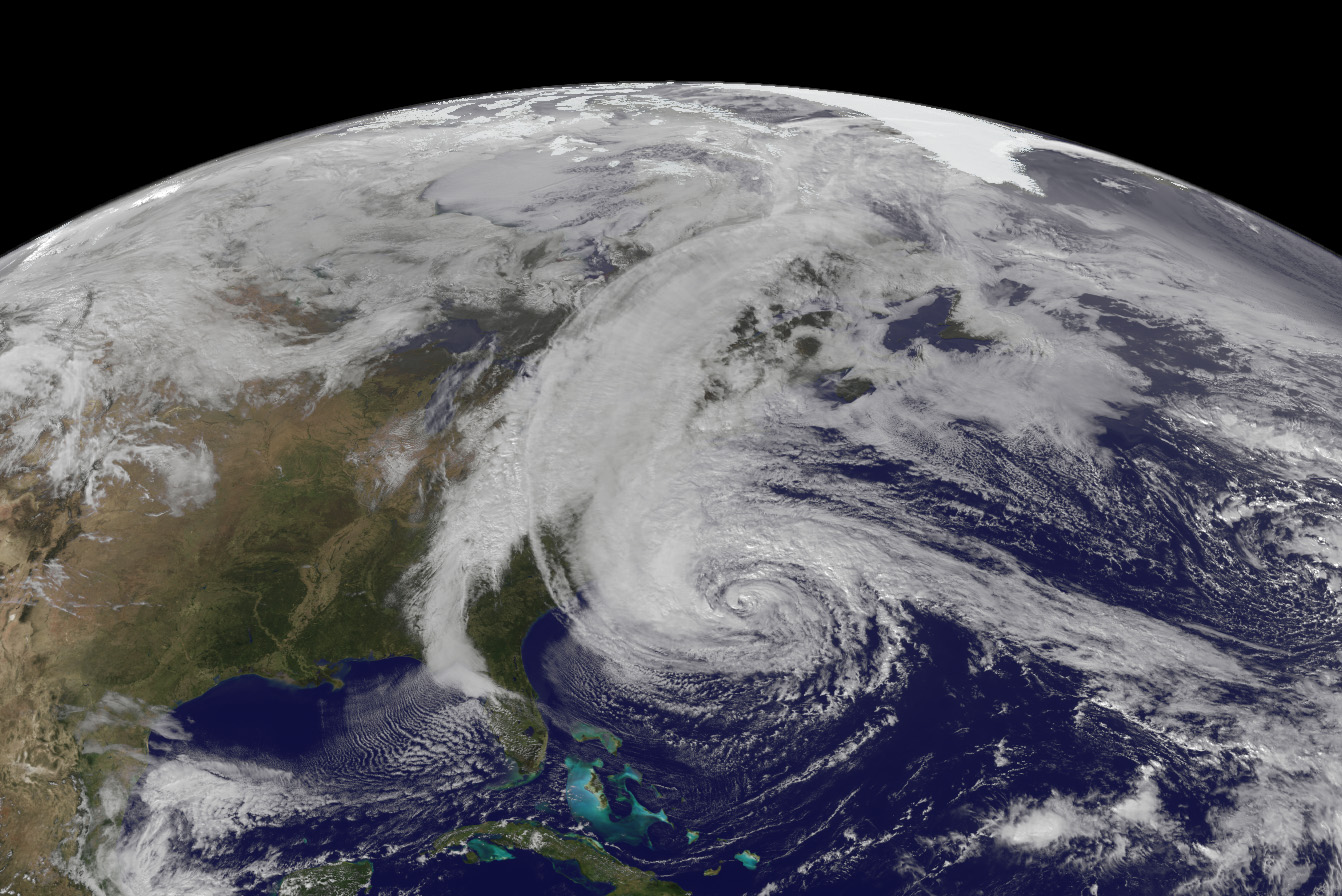

The storm we know as Sandy has gone by several different classifications. Storm classifications are fluid, just as the storms are: what is a Category 3 hurricane in one part of the world might be nothing but a cyclone by the time it reaches another part. “You typically talk about a storm’s category depending on where you are,” says Blumberg. Sandy was, according to the Saffir-Simpson Category Scale (that’s the scale that decides what category a hurricane is, based mostly on wind speed), a Category 2 hurricane when it made landfall in Cuba, early on the morning of October 25th. But when it made landfall near Atlantic City, on the evening of the 29th, it was a tropical cyclone, due to its reduced strength from its trip up the coast. (Well, technically, it was a “post-tropical cyclone,” as it had ventured out of the tropics but retained the wind speeds of a tropical cyclone.) A hurricane is a specific type of tropical cyclone, with sustained winds of at least 74 mph. The Sandy that reached New Jersey was not moving fast enough to retain its hurricane status, so it was a mere tropical cyclone.

It gets even more complicated when we talk about the storm that hit northern Appalachia in West Virginia, western Virginia, and central Pennsylvania. Sandy took an abrupt turn west and south after it made landfall in New Jersey, which means for those areas, Sandy was actually classified as a nor’easter (it was coming from the north and east, you see). So Sandy had lots of names. But none of them was “superstorm.”

On October 29th, Fox News ran a story called “Hurricane Sandy: Five Reasons It’s A Superstorm.” The reasons are indeed valid reasons why Sandy is a very big and scary storm–the awful timing of high tide, arctic air coming down from Canada, that kind of thing. Mostly, the reason it feels okay to give Sandy this scary new name of “superstorm” is that Sandy merged with an unusually cold storm to its west which had been hurling early snows down on West Virginia, forming one giant storm that gave Sandy more power and also pushed it west–very unusual for a tropical cyclone, says Blumberg. So, two storms in one = superstorm, right? Well, no. A super storm, perhaps, as in a “very large or powerful” storm, but not a superstorm. There’s no such thing as a superstorm.

But the phrase “superstorm” took off, perhaps because “post-tropical cyclone” sounds not as scary. And, in the defense of those repeatedly insisting on the superiority of this storm, it was a very awful and destructive weather system! You could make a reasonable argument that the term is descriptive or evocative rather than scientific, and you could make an argument that playing up the super-ness of the storm served the function of scaring people into protecting themselves. But it’s important not to pretend scary-sounding words–or even silly words, like “Frankenstorm”–are scientific classifications. Sandy wasn’t “downgraded from a hurricane to a superstorm.” Sandy was never a superstorm. There are no superstorms.

Read more entries from the Dictionary of Hurricane Sandy here.