Dark Matter Collides With Human Tissue An Average of Once a Minute, Study Finds

A dark matter particle smacks into an average person’s body about once a minute, and careens off oxygen and hydrogen...

A dark matter particle smacks into an average person’s body about once a minute, and careens off oxygen and hydrogen nuclei in your cells, according to theoretical physicists. Dark matter is streaming through you as you read this, most of it unimpeded.

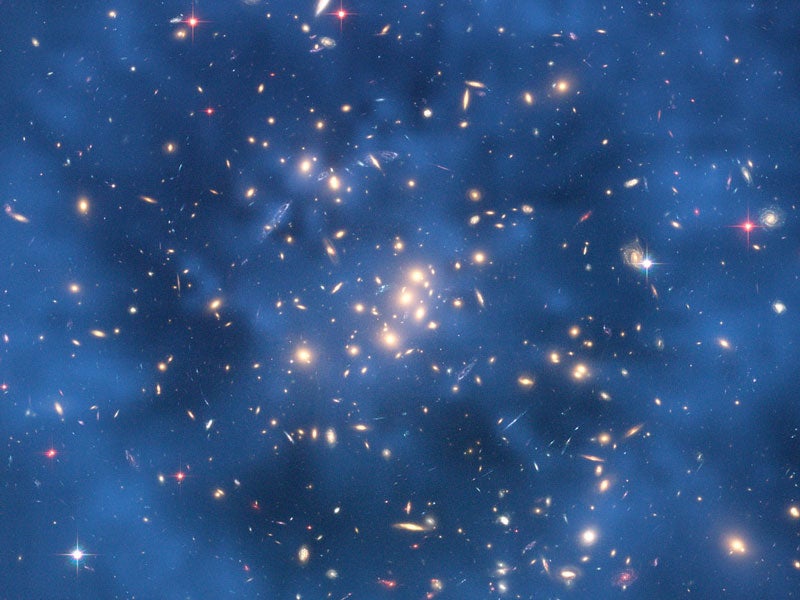

Dark matter is arguably the greatest mystery in modern physics. Observations from multiple sources across a few decades now shows that most of the universe is made of matter we can’t see — hence the name — but no one has been able to find it. One strong candidate for this dark material is called a WIMP, for weakly interacting massive particle, and there are a variety of observatories in Europe and the U.S. that are looking for these things. Some have found promising hints, but others have seen a whole lot of nothing.

Still, cosmologists generally agree there’s a halo of dark matter particles out there, and our solar system and our planet are flying through it. In a new paper, Katherine Freese at the University of Michigan and Christopher Savage at Stockholm University in Sweden thought about what this means for our bodies.

We know dark matter does not interact normally with regular matter — otherwise we’d be able to see it — so that means most of the particles pass through us. But some might interact with a hydrogen or oxygen nucleus, changing their energies or spins. The researchers use a 70-kg human (about 155 pounds) as an example, and calculate how many particles may be careening around based on signals from the DAMA, CoGeNT and CRESST experiments. Of the billions of high-energy WIMPs passing through a body every second, fewer than 10 hit a body’s nuclei in a given year. But lower energy WIMPs make impact much more frequently, around 100,000 collisions per person per year. That’s about one per minute.

What does this mean? Maybe nothing, in terms of impacts on human health — cosmic and solar radiation also rains down on us all the time, and it has many more detrimental effects. But it’s interesting to think that we ourselves could be dark matter detectors. The paper is posted on the astrophysics arXiv preprint server.