Chemist Once Accused of ‘Quasi-Science’ Wins Nobel For Quasicrystal Discovery

Vindication has to be one of the most satisfying effects of a Nobel Prize win — after years of work,...

Vindication has to be one of the most satisfying effects of a Nobel Prize win — after years of work, the scientific community has finally recognized the real weight of a discovery someone probably fought a very long time to prove. So Daniel Shechtman must feel really satisfied today. The Israeli chemist is a Nobel laureate for his discovery of quasicrystals, a unique form of solid matter whose discovery cost him his job and reputation.

In April 1982, Shechtman spotted an odd atomic arrangement through his electron microscope at Johns Hopkins University: A crystal of aluminum and manganese arranged with pentagonal symmetry. It was thought to be impossible — five sides do not a perfectly repeatable structure make. The laws of nature held that the atoms in a solid could be arranged in an amorphous, blob-like pattern, or organized with symmetrical periodicity into crystals. Shechtman saw something that fit neither category.

His research was “extremely controversial,” as the Nobel Assembly put it today. He told his colleagues what he’d seen and they laughed him off, he said in an interview earlier this year. He was eventually asked to leave his research group for “bringing disgrace” to its members, he told the Ha’aretz in April.

Two years later, he finally published his findings, yet the skepticism remained — and it remained bitter, as the AFP explains it. The famous American chemist Linus Pauling once declared at a conference: “Danny Shechtman is talking nonsense. There is no such thing as quasicrystals, only quasi-scientists,” AFP recalls.

But scientists did start to come around. In April 1985, Popular Science covered research by physicists at the University of Pennsylvania who found an icosahedron solid — a solid with 20 triangular faces, 12 vertices and 30 edges, something not found in a crystal.

Then in 1987, scientists in France and Japan were able to repeat the work on a larger scale, allowing the crystals to be examined with x-rays. In the decades since, quasicrystals have mushroomed into a major research field.

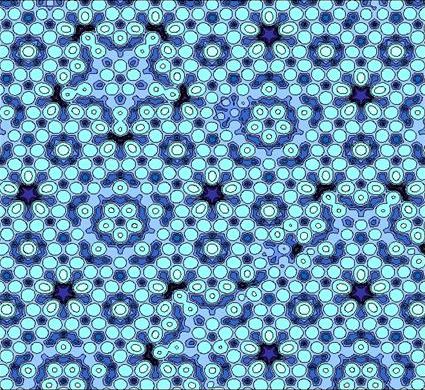

The aperiodic atomic arrangement follows a regular pattern, but they never repeat themselves. These bizarre shapes are found in Islamic art, including at the Alhambra Palace in Spain and the Darb-i Imam Shrine in Iran, the Nobel Assembly notes. The art has helped scientists better understand what quasicrystals look like.

The structures are being studied as possible material for everything from body armor to frying pans, the Nobel Assembly said.

At a press conference afterward, Shechtman said it was a great day for him, and for science. It must be nice to have everyone agree this time.