New Brain-Machine Interface Taps Human Smarts to Enhance Computers’ Abilities, Instead of Vice Versa

Brain-machine interfaces hold potential for a variety of ends, from helping the neurologically or physically disabled communicate and interact with...

Brain-machine interfaces hold potential for a variety of ends, from helping the neurologically or physically disabled communicate and interact with their environments, to creating thought-controlled computers that augment the brain with computing power. A group of researchers at Columbia are turning that model on its ear, using brain power to augment computing tasks. Their device couples the human brain and computers to perform tasks neither could do as efficiently on their own.

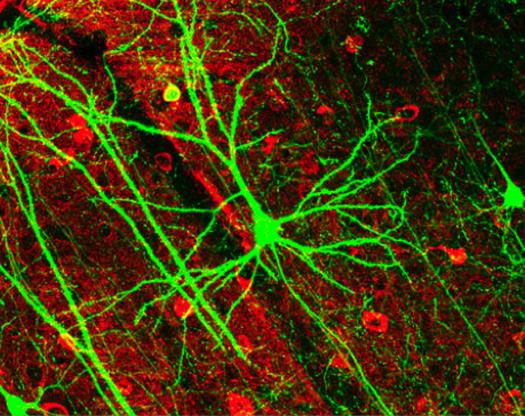

The device, known as C3Vision (cortically coupled computer vision) taps into the fast processing power of the brain to help computer programs manage complex problem, particularly those posed by image recognition. An electroencephalogram (EEG) cap on the head of a human user is used to detect neurological signals in the brain. The computer then flashes images up on the screen at a rate of about ten per second. The conscious brain doesn’t even have time to adequately consider each image, but the subconscious is hard at work.

The system is great at working our problems that computer language has a problem tackling. For instance, it’s easy enough to search for a picture of a bicycle on the Web, but it’s far more difficult for a search engine like Google or Bing to search for something that looks “odd” or perhaps “silly.” The brain, however, can take these less-defined, more abstract qualifiers and very quickly assess whether or not an image fits the term.

The conscious brain doesn’t even have to get involved. The images flash too quickly for a person to rate his or her interest in each one, but the visual pathways in the brain move much more quickly. Machine-learning algorithms can quickly detect the neurological signals that represent the brain’s interest in a given image, and helps the computer to rank the images for interest. If the person sees something interesting or different, the computer knows it even if the person does not.

As such, the system has been used in tests to accurately scan satellite images for the presence of surface-to-air missiles faster than either a human or a machine could alone. Which accounts for DARPA’s interest in the technology; the DoD research arm has sunk $4.6 million into the development of the tech via a spinoff from the university. But the tech could also be used for a variety of other tasks that require the analysis of large volumes of visual data.