Engineering Food With Aromas That Make Us Feel Full

Usually the enticing smell of food is associated with hunger pangs, but researchers in the Netherlands think that foods can...

Usually the enticing smell of food is associated with hunger pangs, but researchers in the Netherlands think that foods can be engineered to release satiating aromas during chewing. This would help combat obesity by stimulating areas of the brain that signal fullness. In a paper published in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, the researchers outline how food products could be tailored to release a higher quality — or a higher quantity — of aromatic food molecules, thus discouraging overeating.

Admittedly, the idea of the smell of food making us feel full rather than hungry seems a bit dubious, but it turns out it’s not. “This is not a crazy paper,” Dr. Linda Bartoshuk, an expert on taste and smell at the University of Florida, told PopSci. “This research, however, is very preliminary.”

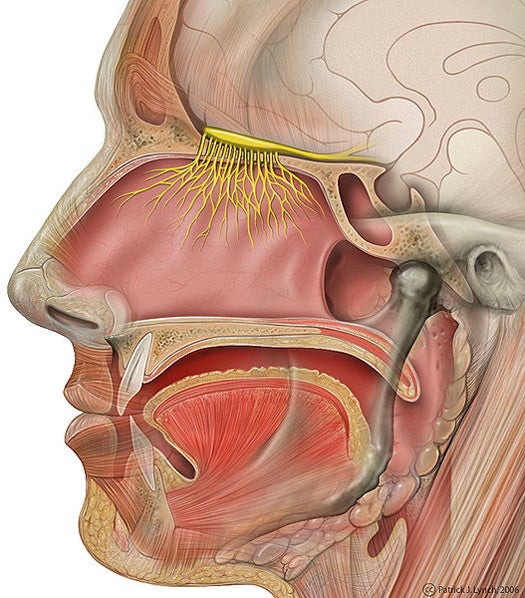

The link between retronasal aroma — that’s the aroma that you smell when you are ingesting food, when molecules from the food come in contact with your olfactory senses from the inside rather than through your nose — and satiation is long established. There are even products on the market — everything from sprinkles you can put on your food to aroma pens — aimed at helping dieters eat less by subjecting them to certain smells that induce satiety. But the Dutch team suggests food itself could be engineered to produce more intense or longer-lasting satiating aromas that will make people feel full more quickly.

The science works like so: When you eat, certain molecules break free from the food as you chew, working their way up to your nasal cavity and to your olfactory sensors. From there, they’ve been shown to stimulate certain areas of the brain connected with satiety, or the feeling of fullness. The problem is, like many processes in the brain, the feeling is based on perception, and that varies from person to person.

The researchers acknowledge the idea that some people perceive retronasal aroma stimuli differently than others, but in their data they do point out one important finding: in tests where subjects were free to eat as much as they wanted, subjects who experienced a higher extent of retronasal aroma release freely chose to consume less food. The findings suggest that if food could be engineered — using additives to increase aftertaste, by making certain aromas linger, or even by packaging food such that it is consumed in smaller bites — could prolong the sensation of retronasal aroma release, making the diner feel more full faster.

“They have not measured the perception of the volatiles [aromatic molecules], and that’s a big piece, because it’s perception of the volatiles, not the volatiles themselves, that affects satiety,” Bartoshuk said. “But there’s every reason to think that increased volatiles will result in increased perception.”

More research is clearly needed, Bartoshuk says, and even then this avenue may not deliver a treatment for overeating. Then there’s the question of whether or not food companies would actually want to tailor food that induces consumers to eat less. But the idea of a mouth-watering burger preprogrammed to be less mouth-watering by the bite is the kind of science that really whets our appetites.