For The First Time, Researchers Edit The Genes Of Human Embryos

Rumors that this research was underway turn out to be true

Rumors have been buzzing for months that a team of Chinese researchers was intending to edit the genes of a human embryo. According to a study published this week in Protein & Cell, the rumors are true. And though the researchers took pains, there’s no doubt that they’ve opened an ethical can of worms that will pit scientists against one another for years to come.

Proponents of embryonic genomic editing point out that it could help eradicate genetic diseases, including fatal ones such as Tay-Sachs disease. But those opposed have compelling arguments, too: the person into whom the embryo develops can’t consent to having her genes changed, and it could have a number of unintended side effects that researchers wouldn’t be able to observe until many years later. These concerns inspired several scientists to write an op-ed, published in Nature last month, advising their colleagues to stop modifying embryos until they could hash out the ethical concerns.

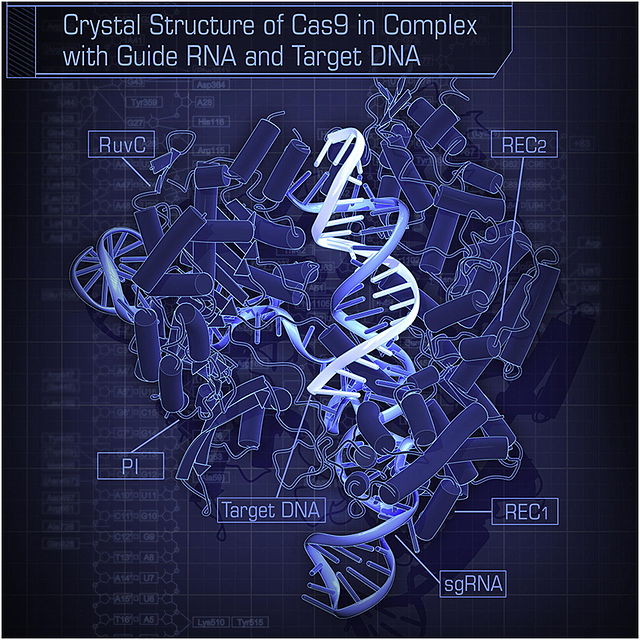

But the team of Chinese researchers, based in Guangzhou, did not heed the warning. They were cautious, however—they selected only non-viable embryos to tinker with, so there was no way the embryos could develop into fetuses. They were using the enzyme CRISPR/Cas9, which binds to particular parts of the genome before splicing it, to remove a tiny part of the gene that causes beta thalassemia, a genetic condition that affects the blood.

They injected the modified DNA into 86 embryos and waited two days. Some of the embryos didn’t survive, but among the 54 that did and were genetically tested, about half of them had the modified genetic material. The technique, it seems, is too immature to consistently give researchers the desired outcome. But the Chinese researchers plan to continue their work, improving the technique enough to be used on normal, viable embryos.

“I believe this is the first report of CRISPR/Cas9 applied to human pre-implantation embryos and as such the study is a landmark, as well as a cautionary tale,” George Daley, a stem-cell biologist at Harvard Medical School in Boston, told Nature News. This paper was rejected by both Nature and Science because of the controversy surrounding it, and the debate is only beginning.