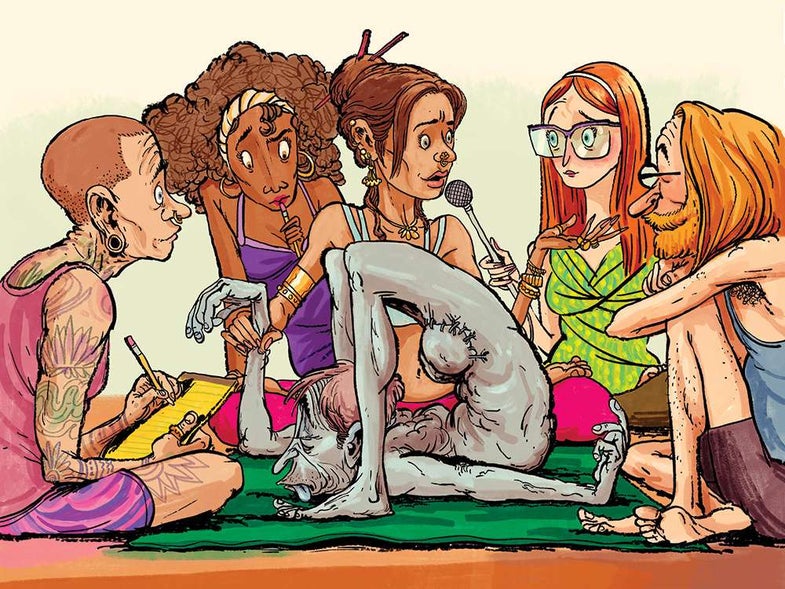

Meet the yogis who hang out in cadaver labs

You can hone your corpse pose by hanging out with actual corpses.

Beverly Boyer knows bodies—the registered massage therapist soothes living muscles every day. But when Boyer describes the first time she peered inside a corpse, her voice lowers as if she’s recalling the start of a great romance. “Everything clicked,” she says. “Everything I had learned through my education—the anatomy, the physiology—I could see it right there.” It’s a Tuesday night in February, and Boyer, standing in the basement of a funeral parlor, is doing her best to share her macabre love interest with others. In 2014, she founded what’s now called the Colorado Learning Center of Human Anatomy, which rents space in a Longmont mortuary, to give other flesh professionals—massage therapists, yoga teachers, acupuncturists, and energy workers, among others—access to deceased and donated bodies. Each week, dozens of Boyer’s students gather here to manipulate the soft tissue of cadavers, hoping to gain anatomical insight to apply to their own day jobs.

Hers is one of a handful of cadaver schools for the nonmedical crowd that has risen up in the past several years. They promise unconventional students a sort of anatomical enlightenment, focusing on the body’s fascial layers, muscular origins, insertion points, nervous systems, and biomechanical functions (and dysfunctions).

As a local lover of science, yoga, and all things strange, I’ve long wondered what these idiosyncratic dissection enthusiasts get out of their evenings with the deceased.

Tonight, I’m watching Boyer run a class for about a dozen yoga instructors. But she is not the teacher. That title belongs to Vesalius—the dead man whose foot the students are now passing around. Just prior to this, the students had nervously chattered while donning paper gowns, rubber gloves, and masks sometimes daubed in eucalyptus oil to staunch the stench of formaldehyde. But with Vesalius’ sole laid bare—whitish-yellow, oddly plush, threaded through with fibrous muscle and tendon—they fall silent.

“Isn’t it beautiful?” asks Boyer. She encourages them to feel the heft of their teacher’s heel in their hands.

As the foot makes its rounds, Boyer removes a towel covering the torso. She lifts layers of muscle and bone from his skinless, dissected midsection. “It looks like turkey,” says one of the students. Someone giggles, then stops abruptly.

Boyer is rooting around for Vesalius’ erector spinae—a muscle group that spans the length of the vertebral column. In yin yoga, the specialty of today’s group of students, one might access it with a long child’s pose, a forward bend that relaxes both the muscle and the fascia that covers it. The theory is that this release activates the parasympathetic nervous system, calming the body’s fight-or-flight impulse and unraveling physical stress.

As Boyer dips her hand into Vesalius’ hollowed-out torso, one student bounces from foot to foot; another’s eyes shine with what look like tears.

Dana Balafas, a bespectacled woman with Instagram-worthy bangs, stands away from the rest of class. As Boyer describes the erector spinae’s role in helping the body fold forward, Balafas suddenly drops her head down to her legs. Boyer pauses to ask if she’s feeling well.

“Yeah,” says Balafas, snapping back upright. She’s just trying to make sense of her own erector spinae.

Not long ago, few who weren’t doctors, coroners, or med students had a chance to handle a dissected cadaver. And as late as the 19th century, the corporeal cleavage that gave medical professionals their best pre-MRI glimpse into bodies came from plundered graves or the victims of public executions. Curious vivisectors broke all kinds of laws and social taboos to practice their craft. “Even doctors and staff at medical schools were involved in grave robbing,” says Raphael Hulkower, an endocrinologist who penned a research article on the history of dissection. The means may have been unsavory, he says, but grave robbing supported students’ desperate need to understand the workings of the biological machines they sought to repair. Even in our age of digital medicine and computer simulations, academics still believe that cadavers are the best way for students to study anatomy. It’s little wonder that yogis, driven as much by a desire to respect the body as to see its inner workings, have gotten into the act. And Colorado—with two other facilities within a 100-mile radius of here regularly offering similar courses to Boyer’s—turns out to be a unique haven for those looking to get out of corpse pose and into some actual corpses. Boyer beat them all by a couple of decades. In 1995, two years into her career as a massage therapist, she persuaded a professor at Ohio State University to give her a tour of the cadaver lab. It would take a while, but she finally got into the business for herself. Nearly 400 students came through her doors in 2016, and more than 700 in 2017. Among those who donate their remains to the stretch-and-release sciences: lawyers, construction workers, nurses, and teachers, most of them from the community and some of whom were yoga practitioners themselves. While still alive, donors can help decide which classes they will teach in the academic afterlife. They can also choose how much Boyer reveals to students about their lives and professions, information that can assist in the teaching. Tonight’s teacher arrived at the center with only two identifiers (88, colon cancer). Boyer has named him Vesalius for a 16th-century Flemish physician known as the founder of modern human anatomy. To encourage her students to connect to Vesalius, she shares the backstory she has given him based on his distinct physiology; she calls him her “rancher” because his right supraspinatus muscle—part of the rotator cuff—carries tension lines that suggest repeated overhead use, lasso-style. And because his knees show hardly any signs of arthritis (very odd for a man his age), Boyer proposes that maybe he spent more time on a horse than his feet. “He had really nice knees,” she says.

Though devoted to my own yoga practice, I’m wary of the exaggerated claims and pseudoscience often associated with the discipline. It might offer stress relief, help with pain management, and make people more flexible, but at its core, yoga is spiritual—and more often than not, spirit and science seem to diverge. So my ears perk up when Boyer veers off the hard-science stuff and pronounces the word “chakra,” the wheel-like energy centers that Eastern religions associate with one’s life force. Is she about to show us some cluster of nerves that can explain the “blockages” or “vibrations” of the third eye, or why a hip-opening yoga pose might realign out-of-whack sacral chakras and restore emotional well-being? Not exactly. She stops short of making any scientific extrapolations, but she’s happy to connect the dots.

“Here’s where his heart chakra would have been,” she says. She gestures toward Vesalius’ thoracic cavity in a moment more of meditative reflection than instruction. “The heart takes earth and stomach and connects it to heaven.”

Vesalius’ heart may connect him to heaven, but his butt is in a plastic bin by his feet. Boyer hands the tissue to a student. “That’s the glute,” she says. “Here, pull.” The student tugs on a long, leathery piece of iliotibial (IT) band.

When attached to a leg, the IT band stretches from the posterior iliac crest above the gluteus maximus to the knee, helping the hip move. Tonight, Boyer uses Vesalius’ backside to demonstrate the resilience of connective tissue.

“Pull harder,” Boyer says. As the student lets it go, it settles back into place. Boyer puts the butt back in the bin.

Boyer conveys a profound respect for people who donate their organs to science. She’s already committed her mortal remains to lie on the same steel slab one day. “Please thank the teachers in your own way tonight,” she tells the students as the class breaks up. Chattiness returns as the trainees slide out of their gowns, shoving used gloves into the trash and washing their hands. The towel-covered bodies still lie splayed on tables beside them. (A few quietly agree that Vesalius does indeed look a lot like turkey jerky.) But from now on, they concede, they’ll see dead people when they downward dog. I gaze around at the mysterious-looking spray bottles, the moisture that drips from the cadavers and down drains in the metal tables, the quote about kindness displayed beside anatomical charts. Balafas tells me she’ll think of Vesalius’ spine whenever she’s tempted to skimp on her stretches, and as she prepares sequences for her yoga students. But having earlier handled the heart of “Miss V,” a teacher who died of brain cancer in her 80s, Balafas now has a curious request: She’d like to see inside the woman’s skull. Balafas’ mother, it turns out, died of the same. Boyer reveals an open cranium with the flick of a towel, explaining where the cancer was located and how little of the brain it compromised. “She has a beautiful brain,” Boyer muses.

Erin Blakemore is a Boulder, Colorado–based journalist and author.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2018 Life/Death issue of Popular Science.