We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

If you are in the market for both a new laptop and a new tablet, a 2-in-1 laptop will give you both in a single device. Think of all the benefits you’ll reap with a device that functions as both a full-fledged computer and a more casual tablet. All it takes is a snap or a rotation for it to go from one to the other. When you travel, you’ll only have to make luggage space for one device instead of two, and the best 2-in-1 laptops are also super-portable when you’re just running around town. If you’re heading out to do errands and want to take your work with you, just disconnect the tablet from the keyboard or flip the device and go.

With 2-in-1 laptops, you won’t have to worry about saving files to two different devices, and you only need one outlet and plug to charge both. Using them can also be a family affair. Adults get to do their work during the day and read in bed at night on the same PC, and the touchscreens make them kid-friendly. The little ones will also love the tablet component. The whole family can stay busy—and happy—with one of the best 2-in-1 laptops.

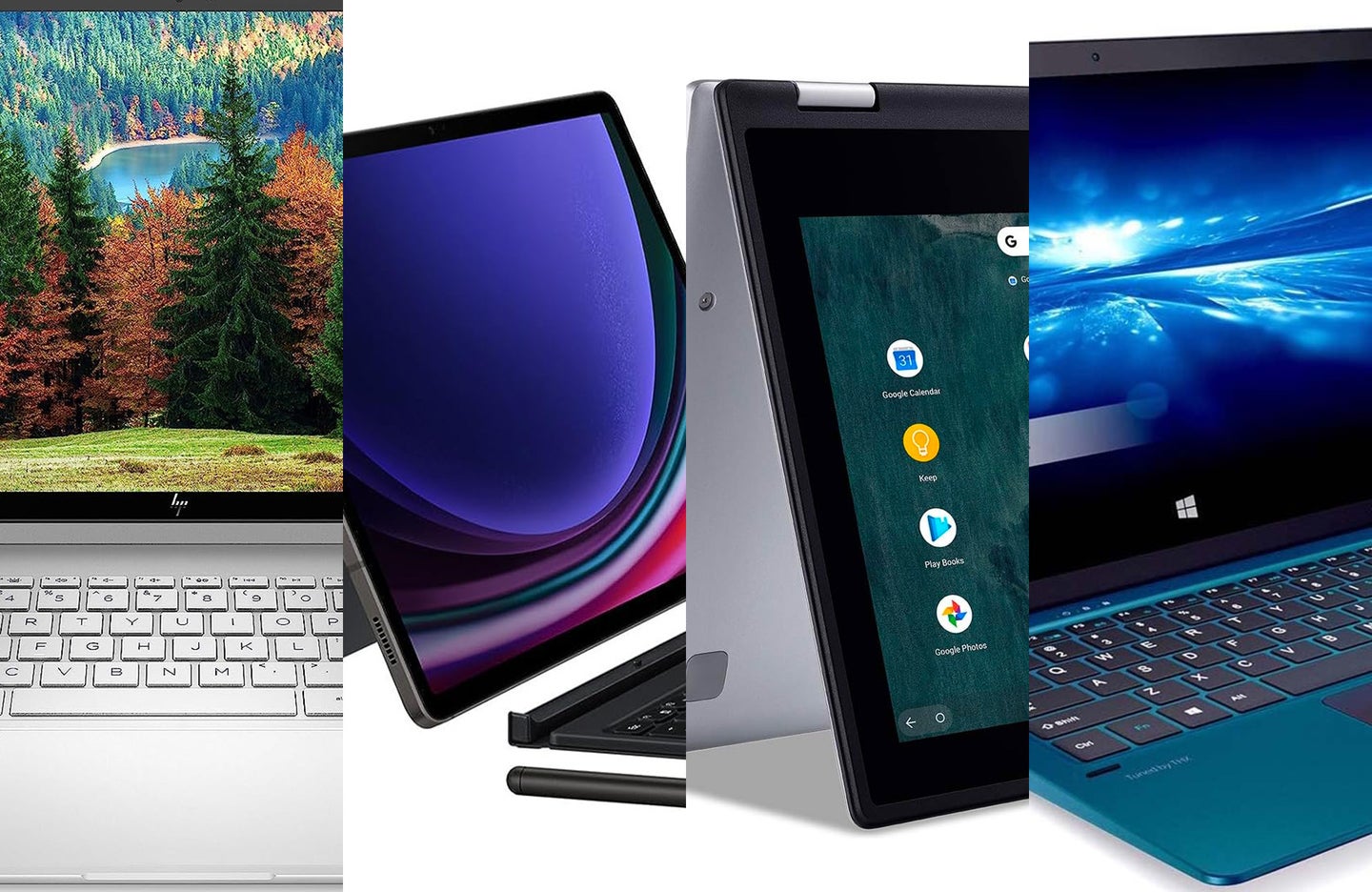

- Best overall: HP Envy X360

- Best convertible: Acer Chromebook Spin 311

- Best for Android users: SAMSUNG Galaxy Tab S9+

- Best with touchscreen: Dell New XPS 13

- Best for speed: Lenovo Chromebook C330

- Best budget: Gateway Touchscreen 11.6 HD 2-in-1 Convertible Laptop

How we chose the best 2-in-1 laptops

In order to find the best 2-in-1 laptops, we looked at user reviews and critical recommendations and performed heavy research. We also looked at past computer and laptop coverage to ensure all picks have specifications to tackle multiple browser windows, streaming, and workflow apps.

The best 2-in-1 laptops: Reviews & Recommendations

Buying a new laptop or tablet can be a stressful undertaking. With so many brands and models to choose from, how do you pick the one that best meets your needs? One of our picks should do just that.

Best overall: HP Envy X360

HP

Specs

- RAM: 12GB

- Storage: 512GB

- Screen size: 15.6 inches

- Battery life: Almost 10 hours

Pros

- Large screen

- Long battery life

- Powerful specs

Cons

- Might be a little large for a commute

With its perfect 1080p high definition, expanded memory and storage, backlit keyboard, and powerhouse 3-cell lithium-ion battery (9 hours and 45 minutes of life), HP’s crowning achievement in 2-in-1 laptops offers a lot more than its relatively bargain-level price tag might suggest. Its convertible design allows it to switch from regular laptop to tent and tablet modes.

Best convertible: Acer Chromebook Spin 311

Acer

Specs

- RAM: 4GB

- Storage: 32GB

- Screen size: 11.6 inches

- Battery life: 10 hours

Pros

- Portable

- Great for surfing the web

- Strong touchscreen

Cons

- Not good for beefier computing

Chromebooks give you access to more than two million Android apps available on Google Play, and this one’s IPS technology and antimicrobial Corning Gorilla Glass 6 touchscreen deliver maximum clarity and detail. It offers limited space compared to other models, but there’s a microSD slot for extra storage, should you need it.

Best for Android users: SAMSUNG Galaxy Tab S9+

Samsung

Specs

- RAM: 12GB

- Storage: 512GB

- Screen size: 12.4 inches

- Battery life: Two days

Pros

- Long battery life

- Can control other Android devices with the tablet

- Water- and dust-resistant

Cons

- Keyboard sold separately

If you’re a big fan of Android apps, meet your match. With this 2-in-1, you’ll have access to all the apps you need without having to do any fancy finagling. Although it’s built mainly for use as a tablet, this model can easily expand into a laptop by attaching it to the separate S9+ keyboard.

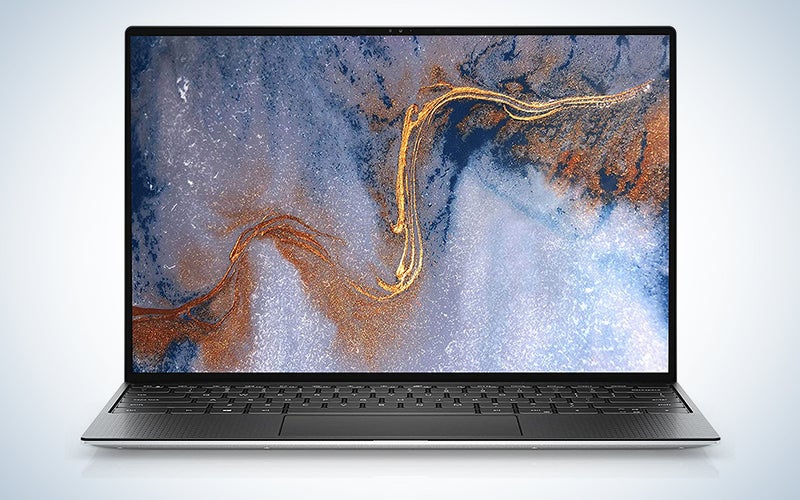

Best with touchscreen: Dell New XPS 13

Dell

Specs

- RAM: 32GB

- Storage: 2 TB

- Screen size: 13.4 inches

- Battery life: 17 hours

Pros

- Loaded with features

- Blue light-reducing screen

- Thin

Cons

- Expensive

It may not be cheap, but this Dell 2-in-1 comes loaded with features, including a sleek aluminum design that’s six percent thinner than the market average, a 2.25mm HD webcam, Dolby Vision, a damage-resistant Corning Gorilla Glass 6 screen, and an Eyesafe display that reduces harmful blue-light emissions. Just touch the power button and let it work its 2-in-1 magic.

Best for speed: Lenovo Chromebook C330

Lenovo

Specs

- RAM: 4GB

- Storage: 64GB

- Screen size: 11.6 inches

- Battery life: 10 hours

Pros

- Compact

- Boots up fast

- 10-point touch screen

Cons

- Reviews note poor customer service from Lenovo

Lenovo laptops boot up quickly, and you won’t have to wait more than a few seconds to get this one started. Its 10-point touch screen further ensures easy maneuverability. Although the RAM and storage meet only the minimum requirements for high efficiency, its compact price and size make it a top 2-in-1 pick.

Best budget: Gateway Touchscreen 11.6 HD 2-in-1 Convertible Laptop

Gateway

Specs

- RAM: 4GB

- Storage: 64GB

- Screen size: 11.6 inches

- Battery life: 8.5 hours

Pros

- Portable

- Lots of ports

- Decent battery life

Cons

- Reviews note flaky Bluetooth

This one has fairly basic functionality with 4GB of RAM, and 64GB storage and is perfect for casual use. If you’re only looking to surf the internet and use Microsoft Word, then the specs are just enough to get the job done. Its fun blue color makes it stand out from the silver and black laptop pack, and its price is phenomenal.

Things to consider when shopping for the best 2-in-1 laptops

Of course, decisions must still be made when searching for the best 2-in-1 laptop. First, do you want a detachable or convertible device? Next, how do you want the touch screen to work? If you are using it as a tablet outdoors or while multitasking, this will become an especially crucial detail. Should you go with a Google Chromebook or a Windows device? The operating system will have a huge effect on the apps you’re able to use. Another question: How long does it take to boot up and complete tasks? Finally, how good is the sound and screen resolution? The gamers and movie buffs in your household will definitely want to know.

Should you go detachable or convertible?

The best 2-in-1 laptops come in two different forms: detachable and convertible. The former allows the screen to be completely detached from the keyboard for use as a tablet. That solves any bulk issues with one snap. Extra portability is obviously the biggest benefit of a detachable 2-in-1, and it gives you a lighter, more traditional tablet experience. Apple disciples take note: The brand has not yet entered the 2-in-1 market, but to get the 2-in-1 laptop experience with Apple, you can pair an iPad Pro with a smart keypad.

With convertible 2-in-1 laptops, the screen swivels or folds in different directions and at different angles while remaining attached to the keyboard. You can use it in regular laptop form manipulate it into an upside-down V shape, or bend the keypad back and face down to watch movies. If you want to read in bed or use it while in transit, you can bend it flat so that it functions as a tablet. The main drawback here is that if you can’t detach the keyboard, it will be bulkier than the average tablet.

In the end, the choice between detachable and convertible will come down to personal taste. Convertibles are best if you will be using the device primarily as a laptop, as they tend to be sturdier and have superior keyboards. If you’re frequently on the run and want to avoid bulk, a detachable 2-in-1 will probably be more suited to your lifestyle needs.

What about all your apps?

If you have favorite Android or iOS apps, not all of them might be available in a 2-in-1 that’s supported by Windows. Meanwhile, a Google Chromebook supported by Chrome OS will let you access all the Android apps in the Google Play Store. Still, remember, certain apps that were designed primarily for use with laptops might not work as well in tablet mode.

There are, thankfully, ways around the app and OS limitations. If you are part of the Windows Insider program, you can now run Android mobile apps on both your Windows 10 laptop and supported Samsung devices. You simply pin your favorite Android apps to the taskbar or the start menu of your laptop using the Your Phone app. Once accessible, you can use the apps without installing them on your laptop, even when they aren’t open on your phone. For now, this only works if you have a Samsung Galaxy phone, and it must be connected to the same WiFi network as your phone.

The main takeaway here is this: If you are very particular about your apps and how they work, the supporting operating system should be a major consideration. Even if you get the best 2-in-1 laptop that money can buy, you might want to hang on to your smartphone and keep it close … just in case.

How does the touchscreen work?

Most of us are accustomed to mouse-operated laptops, but touch screens have their place, particularly with tablets. Although they’re fairly straightforward, several variables should be considered when evaluating a touchscreen. If you’re outside in cold weather, will it respond to your fingers while you’re wearing gloves? Also, moist fingers won’t activate some screens, which might be frustrating if you’re in a wet situation and can’t immediately dry them.

Certain laptop activities require a mouse, but with Windows and Google both supporting touch screens, they’re not just for tablets anymore. A responsive touchscreen is an especially important 2-in-1 laptop feature if young children are using it since their fingers tend to be stickier than most. Smudges left by their fingerprints may not be your only touchscreen issue. Some apps, like File Explorer, were designed with a keyboard and mouse in mind, so they might not be as user-friendly when you access them in tablet mode.

If you go for a brand that allows you to use a stylus to input information, you’ll want to be sure it has palm-rejection technology. With that feature, the 2-in-1 will respond only to the stylus and not to another part of your hand that’s touching the screen.

How important is speed to you?

A traditional laptop will probably get the job done most efficiently when it comes to complicated tasks that require a graphics card, like video editing and gaming. If you’re a casual user and speed is key, you’ll get more mileage—and cover it a lot more quickly—with the best 2-in-1 laptop than you would with just a tablet. They do, after all, feature full PC operating systems and faster processors.

Speed does tend to vary among 2-in-1 laptops, so to be sure you get the fastest bang for your bucks, make a checklist: Does it take forever to turn on and off? How easy is it to open programs and apps? Can you do what you need to do efficiently without wasting time watching a spinning wheel?

One thing that will affect the speed in a major way is the memory (RAM) and storage capacity of your 2-in-1. Since computers tend to slow down as they begin to run out of memory and space, you should get one that can hold as much memory and storage as possible. Light casual users who won’t be storing their entire life on a computer can probably get by with 4GB of RAM and 250GB of storage, but to stay on the safe — and fast—side, you should go as high with both as your finances will take you.

Looks (and sound) matter

What good is a 2-in-1 if it delivers crappy sound and screen resolution? You should approach buying yours the same way you might approach buying a new television or speaker. The sound should be clear and crisp without requiring further amplification. Even the best 2-in-1 laptops won’t give you audio that’s as Hi-Fi as that of a cheap soundbar, but if you are going to be watching a lot of movies and videos online or playing music on iTunes or Spotify, you shouldn’t have to strain to hear what’s going on.

Keep this in mind when assessing sound: The fans that keep the best 2-in-1 laptops from overheating might interfere with the audio, so to offset any potential effect, at least 8GB of RAM/memory is recommended. High-quality multimedia demands that your device processes data at high speeds, so more firepower means better audio while listening to music or watching movies.

Alas, nothing you screen on even the best 2-in-1 laptops will give you movie cinema or even 55-inch TV gorgeousness, but high definition maximizes viewing pleasure. The base HD standard is 1920×1080, or 1080p, while many computers now ofter 4K. Some brands pack on features that allow users to approximate the cinematic experience more closely, but if you’re in the HD range, you’re already on your way.

FAQs

Q: How much does a 2-in-1 laptop cost?

A 2-in-1 laptop costs between $140-$2,500 depending on specs.

Q: Are 2-in-1 laptops good for gaming?

They’re good for casual gaming, but you’ll want to invest in a proper gaming rig if you’re a hardcore PC gamer. Most 2-in-1 laptops don’t have the framerate and processing specs to make your games shine.

Q: Are 2-in-1 laptops worth it?

We think so, considering you get two devices in one. You can write your notes by hand on the touchscreen, or type them out. You’re not limited to how you can use your computer. 2-in-1 laptops are also smaller than others on the market and offer excellent battery life.

Final thoughts on the best 2-in-1 laptops

- Best overall: HP Envy X360

- Best convertible: Acer Chromebook Spin 311

- Best for Android users: SAMSUNG Galaxy Tab S9+

- Best with touch screen: Dell New XPS 13

- Best for speed: Lenovo Chromebook C330

- Best budget: Gateway Touchscreen 11.6 HD 2-in-1 Convertible Laptop

The best 2-in-1 laptops will do more for you than travel well. It’s great to have both your laptop and tablet in one place, but it’s even better if you don’t have to give up any of the benefits of having two separate devices. A number of brands are making 2-in-1 laptops with superior audio and visuals, and since Chromebooks run on the Google operating system instead of Windows 10, if you go with a Samsung Galaxy Chromebook or any other Chromebook model, you’ll be able to access your favorite Google Play Store apps with minimal hassle. All the music you want to listen to, the movies you want to watch, and the games you want to play are just a tap of a touch screen away.

Why trust us

Popular Science started writing about technology more than 150 years ago. There was no such thing as “gadget writing” when we published our first issue in 1872, but if there was, our mission to demystify the world of innovation for everyday readers means we would have been all over it. Here in the present, PopSci is fully committed to helping readers navigate the increasingly intimidating array of devices on the market right now.

Our writers and editors have combined decades of experience covering and reviewing consumer electronics. We each have our own obsessive specialties—from high-end audio to video games to cameras and beyond—but when we’re reviewing devices outside of our immediate wheelhouses, we do our best to seek out trustworthy voices and opinions to help guide people to the very best recommendations. We know we don’t know everything, but we’re excited to live through the analysis paralysis that internet shopping can spur so readers don’t have to.