How environmentalists are battling fertilizer companies behind Florida’s toxic waste mountains

There are hundreds of millions of tons of phosphogypsum stacks across the U.S.

This story was originally featured on Undark.

In mid-September of 2016 in Tampa, Florida, News Channel 8 reporter Steve Andrews received an alarming phone call. A sinkhole had opened in Mulberry, a small city in Polk County about 30 miles to the east.

“I went up to the assignment desk and asked them to send the chopper up,” Andrews, who retired in 2020, recounted. “The guys radioed back and said, ‘Man, this looks like something from the moon.’” He later added: “It looked like a crater, like you could just drop down straight to hell.”

The sinkhole, which measured 152 feet across at its widest point and 220 feet deep as of October of that year, had opened beneath a 700-acre phosphogypsum stack, a pyramid-like structure of radioactive waste created during the fertilizer production process. The sinkhole sent 215 million gallons of acidic water into the Floridan aquifer, a major source of drinking water for the state.

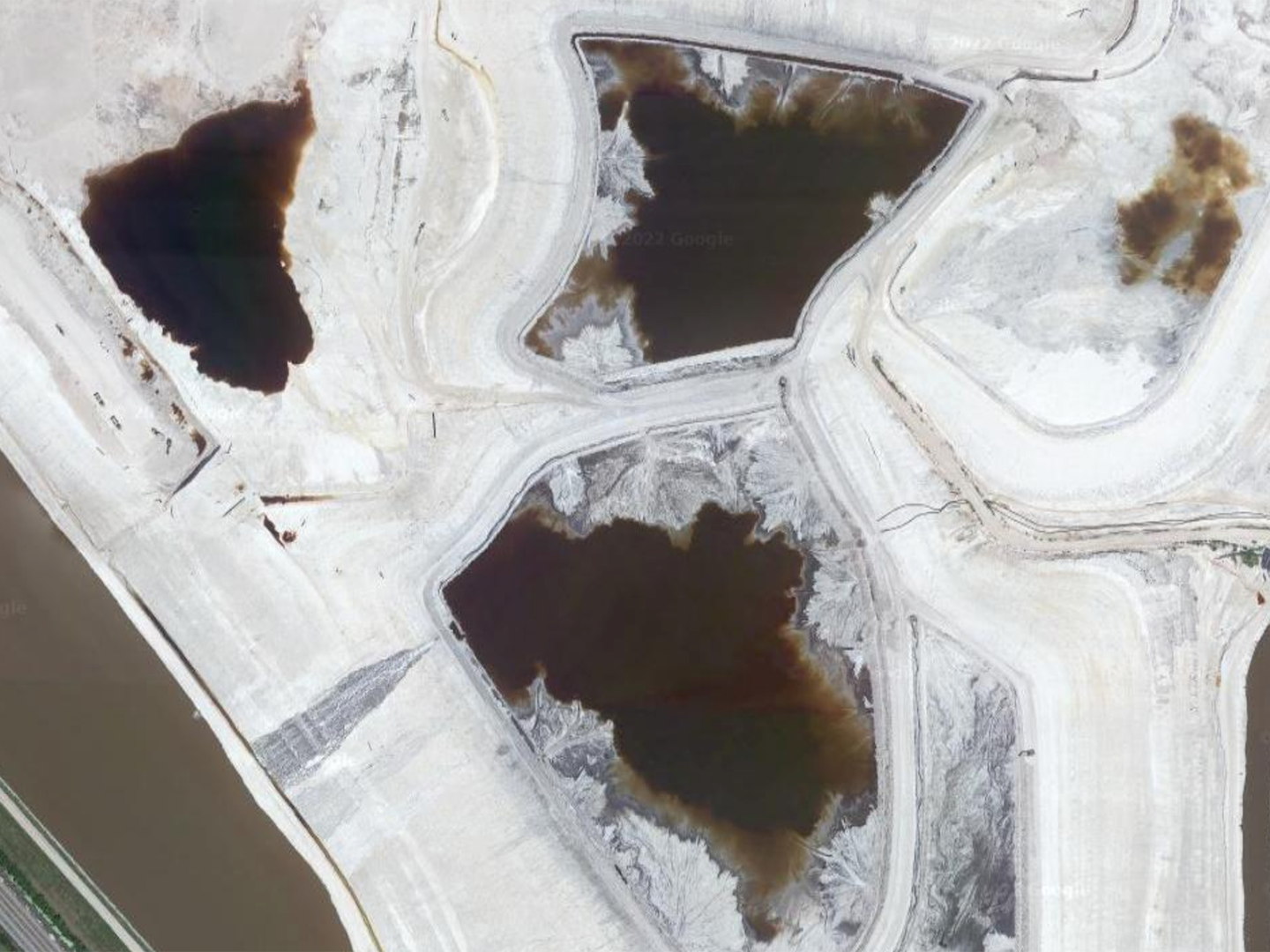

According to a 2019 report from the Fertilizer Institute, an estimated 734 million tons of phosphogypsum have accumulated in the United States—a number the industry group projected to steadily increase each year. That material sits in more than 70 similar open-air piles, which can be hundreds of feet tall and hundreds of acres wide, rising above the horizon like powdery mountains the color of ash.

Fertilizer is a lucrative business, but for every ton of phosphoric acid produced, approximately 5 tons of phosphogypsum are too. The waste can contain substances that are dangerous to human health in large quantities, including arsenic, cadmium, and chromium. It also holds uranium, thorium, and radium, and emits radon gas. Radon is particularly concerning to health officials, and is the leading cause of lung cancer for non-smokers, according to Environmental Protection Agency estimates.

About a third of the country’s phosphogypsum stacks are in Florida. The stack in Mulberry is managed by Mosaic, a Fortune 500 company with significant political clout in the state, and which produces the majority of phosphate fertilizer in the U.S. In 2015, the EPA and the Department of Justice reached a settlement with Mosaic to address alleged violations of the federal Resource Conservation and Recovery Act related to the proper storage and disposal of hazardous waste at sites in Florida and Louisiana. In response to an emailed request for comment, Jackie Barron, a spokesperson for Mosaic, wrote: “The company made the decision to settle the matter and move forward.”

“It’s important to note the debate involved the handling of hazardous waste on-site,” she added. “There was never any action or concern involving any kind of off-site impact.”

Though Mosaic had immediately reported the 2016 sinkhole—or what the company called a “water loss incident”—to the EPA, the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, and Polk County, no one alerted the local community for three weeks.

“There was a lot of anger that the state didn’t make it public,” Andrews said. “People felt that they were being put in danger, that a state was maybe too cozy with a big industry.” (DEP did not respond to request for comment on the criticism. A Polk County representative responded that Mosaic notified the appropriate state and federal agencies; the representative did not address the delay in notifying the public. A spokesperson from the EPA also confirmed that Mosaic notified the appropriate agencies, including the National Response Center and the State Watch Office within the Division of Emergency Management, and noted that, “Both emergency center notifications are publicly available immediately upon entry into the system.”)

Mosaic reported that there were “no offsite impacts from the incident” according to extensive monitoring data and, in May 2018, plugged the sinkhole with 20,000 cubic yards of grout. The company says it has updated its systems to monitor the site.

Rules regarding phosphogypsum have long been in place, but regulation of the waste is limited on the federal level. Since 1989, the EPA has mandated—with some exceptions—that phosphate producers dispose of phosphogypsum in the stacks because of the risk that it could emit radon. (According to the EPA, a crust forms on the stacks as the material dries out, limiting the amount of radon that can escape and protecting the waste from getting blown around by the wind.)

A 2019 Fertilizer Institute report states that 85 percent of phosphogypsum around the world is discarded or stored each year. The rest is used as a soil amendment, agricultural fertilizer, or in building materials. But gypsum stacks and wastewater from phosphoric acid production are exempt from the EPA’s hazardous waste standards, which establish base federal criteria for managing waste from “cradle to grave.” Instead, states are responsible for managing those materials.

Industry officials maintain that existing environmental standards are already strict enough. But environmental advocates disagree: In February 2021, the Center for Biological Diversity and People for Protecting Peace River filed a petition with the EPA on behalf of more than a dozen environmental groups, asking the agency to change how it regulates the disposal of phosphogypsum and process wastewater.

The EPA has so far denied one part of the environmentalists’ formal petition—a request to require testing of phosphogypsum and process wastewater. In a May 2021 letter to the petitioners, the agency told them they did “not set forth the facts establishing that it is necessary for the Agency to issue such a rule.” The EPA told Undark that it is still reviewing the rest of the petition, but did not say when it will complete its full response. And as the petitioners await the EPA’s answer, they say they are hopeful that the Biden administration will be amenable to their request.

“We hope it moves in the right direction, but changes on the federal level can take quite some time,” said Glenn Compton, the chairman of environmental organization ManaSota-88, one of the groups participating in the petition. “So I can’t say I’m optimistic. I would say I’m hopeful.”

Phosphogypsum stacks have a long history in Florida. On Dec. 12, 1983, west of Polk County, the Hillsborough Board of County Commissioners held a public hearing to consider a request by the Gardinier chemical company to open a new phosphogypsum stack. (Gardinier was later acquired by Cargill, which in turn formed Mosaic through a merger between its crop nutrition division and mining and production company IMC Global in 2004. Cargill split from Mosaic in 2011.) The stack would be built near Progress Village, a lower-middle income Black community, near Tampa, as well as an elementary school. That evening, the room was so packed with people that the meeting had to be postponed and moved to a larger space.

Over the following months, hundreds of concerned community members attended public hearings about the proposed stack. Gary Lyman, an oncologist and professor of medicine at the University of South Florida at the time, submitted a report to the board suggesting that radioactive phosphogypsum could pose a health risk.

“It didn’t seem to make sense to any of us that you’d take a chance with children just because the community is in an area somewhat impoverished and can’t legally fight a company,” Lyman told Undark. County officials ultimately approved the new stack in August 1984.

A couple months later, the Federal Register reported that the EPA’s initial risk assessments for phosphogypsum stacks found that “individual lifetime risks from exposure to air emissions from these piles may be as high as eight in 10,000. Population risks may be on the order of one fatal cancer per year.”

“We hope it moves in the right direction, but changes on the federal level can take quite some time,” said Compton. “So I can’t say I’m optimistic. I would say I’m hopeful.”

In 1985, the Journal of the American Medical Association published a separate report by Lyman and colleagues that found a correlation between high levels of radiation contamination in groundwater near phosphate ore deposits and increased rates of leukemia.

That same year, researchers examined mortality among phosphate fertilizer production workers who worked at a Florida plant between 1951 and 1976, before the federal government updated mining safety legislation. In a 2015 update, researchers found elevated levels of lung cancer and leukemia in workers as compared to both the broader U.S. and Florida.

In 1988, Lyman and other researchers found an elevated risk of lung cancer for male nonsmokers who lived in the central Florida phosphate mining region. There appear to be no other comprehensive epidemiological studies that evaluate whether phosphate mining or phosphogypsum pose a threat to human health. Carl Cranor, a professor of legal and moral philosophy at the University of California at Riverside, has written extensively about toxic threats to public health, and said there are many obstacles to doing that kind of work, including finding funding.

“They have to find resources to process results,” he said, adding that they also have to find individuals who were exposed and determine how much they were exposed. “All of that takes time and expertise and effort,” he said. “Those are barriers.”

A few years before Floridians began to argue over the proposed phosphogypsum stack in Hillsborough County, the federal government reevaluated how it would address the growing problem of municipal and industrial waste. Congress had enacted the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act in 1976, by which it would govern the disposal of both hazardous waste and solid waste.

The RCRA rules were updated in 1980 to include an amendment—called the Bevill exclusion, named for Tom Bevill, a Democratic Congressman from Alabama and the son of a coal miner—that allowed certain wastes to be excluded from federal regulation as a hazardous waste. The exclusions were pending an EPA study on the potential adverse health and environmental risks of each waste. Phosphogypsum and related wastewater were among the 20 mineral processing wastes that the EPA considered for exemption.

In July 1990, the EPA published its findings on the mineral processing wastes, stating that both active and inactive phosphogypsum stacks and wastewater cooling ponds for which there was data had caused groundwater contamination and that the wastes contained high levels of radon. But the agency also found that regulatory compliance under the more stringent program could be cost prohibitive for the industry. Because of that high cost, the EPA tentatively determined that the RCRA’s less stringent rules would apply to phosphogypsum and process wastewater.

The EPA then created a committee to assess whether phosphogypsum and process wastewater could be regulated under the Toxic Substances Control Act, which regulates chemicals produced or imported into the U.S., but the committee was unable to identify any suitable changes that could sufficiently reduce the volume or toxicity of phosphogypsum or process wastewater. (In response to an interview request from Undark, the EPA did not make anyone available.) The RCRA’s non-hazardous waste program requires states to implement federal regulations and allows states to set stricter requirements.

In an email to Undark, spokesperson Dee Ann Miller of the Florida Department of Environmental Protection wrote that the state has “some of the most stringent rules” for permitting and regulating phosphogypsum stacks, which include criteria for the “construction, operation, maintenance, inspection, environmental monitoring, closure, and long-term care” of closed stacks. For example, the state of Florida mandates that the stacks have protective liners. Florida also requires owners of the stacks to prove that they have the financial means to close and maintain them in the long term.

In March 2004, a U.S. House of Representatives’ subcommittee held a hearing at the Southwest Florida Water Management District headquarters to address the longstanding issue of the mountains of phosphogypsum piling up across the state. During the hearing, researchers discussed their proposed uses for phosphogypsum, including road construction filler, landfill cover, erosion control, and cat litter.

The EPA had previously banned the use of the waste in road construction, citing concerns that homes could one day be built on top of abandoned roads, exposing residents to radon. At the March hearing, then-Rep. Adam Putnam, the subcommittee’s chairman, pressed Elizabeth Cotsworth, then the director of the EPA’s Office of Radiation and Indoor Air, on why the agency had issued the ban, as well as the agency’s perceived unwillingness to work with the industry to consider new uses for the material.

Cotsworth told Undark that a focused and specific hearing of that nature was unusual and, in fact, the phosphogypsum hearing was the only field congressional hearing of her career. “I thought it was an effort to embarrass the agency to make us look like pinheaded bureaucrats that didn’t listen,” Cotsworth said. “That we were not just overly conservative and inconsistent in decision-making, but that we’d been sloppy. We were kind of in the crosshairs in our processes and our science and our decision-making.” (Putnam did not respond to multiple requests for comment from Undark.)

But critics maintain that the standards across the U.S. are not only inconsistent across states, but insufficient. “That’s why we’re petitioning the federal government to take over responsibilities,” said Jaclyn Lopez, the Florida director of the Center for Biological Diversity. “Because the state has shown itself incapable or unwilling to do the job well enough.”

The 2021 petition asks the EPA to reverse the Bevill Amendment, to regulate phosphogypsum and process wastewater under the more stringent waste rules of the RCRA, initiate the process to evaluate the wastes under the Toxic Substances Control Act, require testing of the wastes to ensure they do not present an unreasonable risk of injury to human health and the environment, and issue a determination that using phosphogypsum as filler in road construction is a significant new use in order to prohibit or limit it.

Phosphate mining is a powerful economic and political force in Florida. A 2016 economic impact study prepared for Port Tampa Bay found that the phosphatic fertilizer industry generated $12.2 billion in total economic value to that region alone.

Mosaic owns more than 317,000 acres of property in central Florida, making it a “significant landowner” in the state by its own estimation. It has spent millions on lobbying and political contributions at the local, state, and federal levels, according to lobbying disclosure and campaign finance records. When asked to comment on those contributions, Barron, the spokesperson, replied that “Mosaic supports various campaigns much like many other companies and individuals.”

When he was governor of Florida in 2013, Sen. Rick Scott held $14,000 of Mosaic stock, according to a public disclosure of financial interest filed with the Florida Commission on Ethics. (Representatives for Scott did not respond to a list of emailed questions.) Political figures have at times taken an active role in advocating for the industry. EPA scientists had been concerned about the radiation levels around reclaimed mines in Lakeland, Florida, since at least the 1970s, according to reporting by the Center for Public Integrity. But in 2014, the agency abandoned its plan to clean up a contaminated site after state elected officials intervened.

Mosaic sought to establish a relationship with the EPA during the Trump administration. In June 2017, Katie Walsh, a Republican National Committee official emailed the EPA’s policy chief, requesting a meeting between Mosaic’s president and CEO, Joc O’Rourke, and Scott Pruitt, EPA administrator at the time. In the email, made public through a lawsuit brought against the EPA by the Sierra Club, an environmental nonprofit, Walsh noted that Mosaic had been “egregiously over regulated during the Obama administration,” a situation that had placed an “unnecessary and costly regulatory burden” on the company.

Critics maintain that the standards across the U.S. are not only inconsistent across states, but insufficient. “That’s why we’re petitioning the federal government to take over responsibilities,” said Lopez.

Agency emails show that in August 2017, EPA officials were scheduling a dinner with Eileen Stuart, Mosaic’s then-vice president of government and regulatory affairs, who was involved with the company’s lobbying efforts. The email noted that Stuart was close to then-Gov. Scott and former Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi. Stuart, who is no longer with Mosaic, told Undark the meeting never took place because of scheduling problems, but gave no additional comment.

When asked to comment on whether Mosaic had ever met with EPA officials, Barron replied that the company has “regular meetings with all of the government entities that regulate the industry, which include those at the county, state, and federal level.”

In October of 2020, Trump’s EPA reversed the long-standing rule that phosphogypsum could not be used in road construction. The decision came nearly 30 years after the EPA had made its determination that the material was unsafe to use in roads. The industry had long appealed the EPA to allow alternative uses of phosphogypsum, but this was the first time the agency had budged.

In 2021, the Biden administration withdrew the approval, following a lawsuit filed by the Center for Biological Diversity and other groups.

Lopez of the Center for Biological Diversity pointed out that the Biden administration has repeatedly stated its commitment to environmental justice. “Phosphogypsum presents a significant environmental justice risk that needs to be addressed,” she said. Approving the petition “would be consistent with the administration’s stated priorities of protecting vulnerable communities from disproportionate harm from corporate polluters.”

In April 2021, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis declared a state of emergency in Manatee, Hillsborough, and Pinellas counties, requiring the evacuation of more than 300 homes. The plastic liner of a 77-acre retention pond on top of a phosphogypsum stack at Piney Point had leaked, threatening to inundate the surrounding community with 460 million gallons of acidic water.

To avoid a major flood, the state’s environmental agency ordered that more than 200 million gallons of the water, which had been sitting atop the phosphogypsum stack, be discharged into Port Manatee, allowing field crews to repair the leak. The crisis prompted Florida lawmakers to set aside $100 million to clean up Piney Point and Gov. DeSantis ordered DEP to close the facility. By mid-April the leak had been temporarily repaired. However, in early January 2022, the state announced it had identified “three low-volume seepage areas” and was working to contain them. According to public announcements made that month, “There continues to be no indication of any concern with the integrity or stability of the stack system, and there are no offsite discharges occurring at this time.”

Environmentalists say the ongoing problems at the site show why stricter regulations are necessary, and have filed a lawsuit against the Florida Department of Environmental Protection and others. Meanwhile, in a 100-page document opposing the pending EPA petition from the Center for Biological Diversity and other environmental groups, the Fertilizer Institute said that between the existing federal and national regulations, some of which were enacted after the Bevill Amendment, along with enforcement actions related to the consent decrees, oversight is already comprehensive and sufficient.

In a separate letter, the Fertilizer Institute’s vice president of government affairs Ed Thomas emphasized that the Piney Point facility “is not representative of phosphate facilities currently in operation” because phosphoric acid production had stopped there in 1999.

The EPA has never before approved the reversal of a Bevill Amendment applied to a mining waste. But Louella Phillips, an environmentalist who lives in Mulberry, Florida, at the center of four different stacks, said she hopes that the coming responses from the agency will help resolve what she sees as an environmental justice issue.

“People who live in an environment like this aren’t getting justice,” said Phillips. “Who’s going to take care of the phosphogypsum when they leave? You can’t clean that up.”

Bianca Fortis is a journalist based in Brooklyn, New York. This story was supported by a grant from the Pulitzer Center.