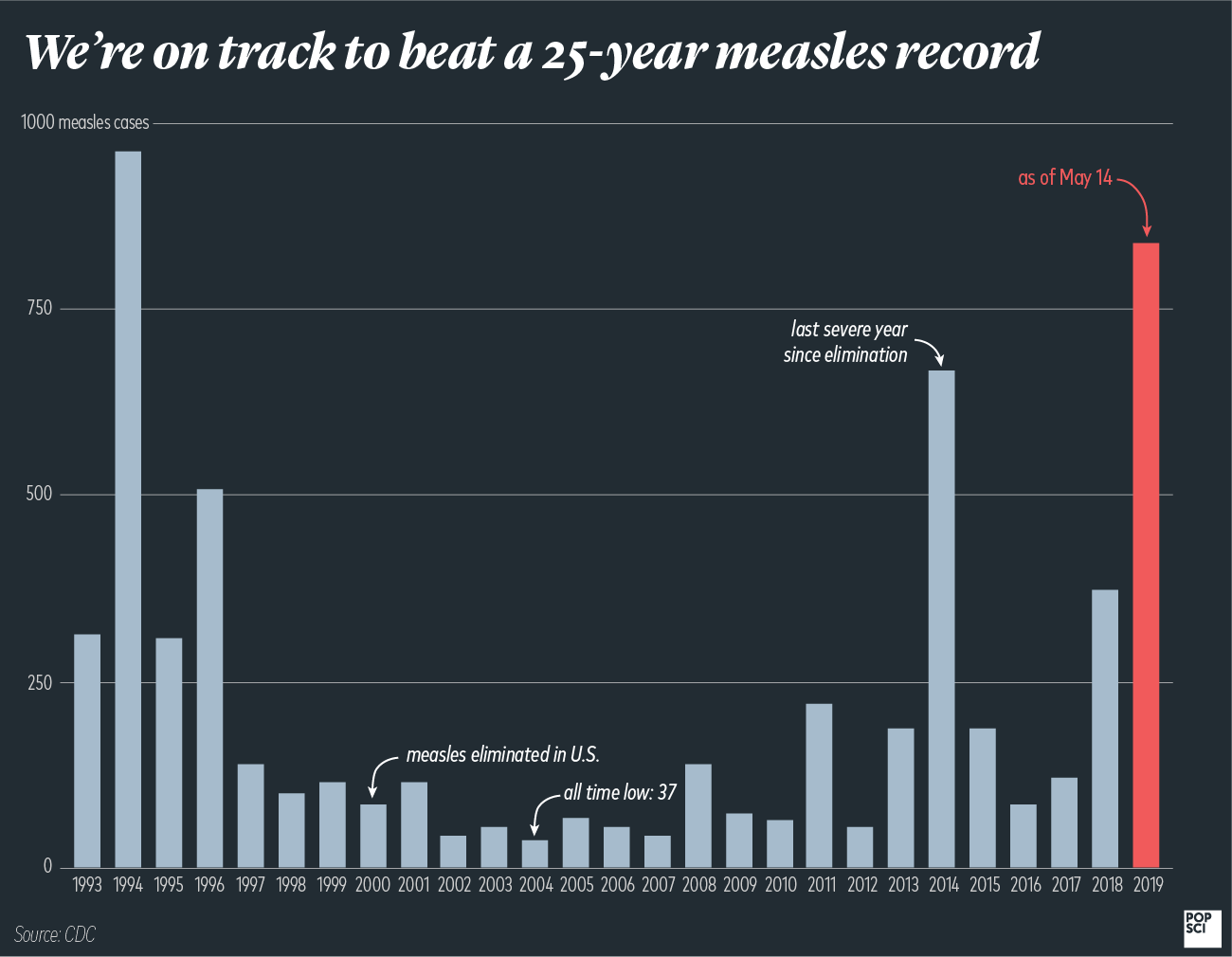

We’re barreling toward a 25-year measles record

A regularly-updated resource to keep you informed.

With seven states in the midst of 10 separate outbreaks, 2019 is now officially one of the worst years for measles in a long time. The U.S. is up to 839 total cases and counting. That’s 467 more than occurred in all of 2018, and makes this the most severe year for measles in 25 years—and it’s looking like we’re even on track to break that record.

That’s largely due to the three outbreaks in Washington state and New York. Clark County, Washington has officially declared its measles outbreak over, but confirmed 71 cases for 2019, and showed connections between this outbreak and cases in Oregon and Georgia. The CDC confirmed that the ongoing situations in Brooklyn and Rockland County, New York, are “among the largest and longest lasting since measles elimination in 2000,” and cautioned that “the longer these outbreaks continue, the greater chance measles will again get a sustained foothold in the United States.” Since 2000, all measles outbreaks have stemmed from unvaccinated people traveling in or out of the U.S. and catching the virus elsewhere. But if enough people get sick at once, we could go back to having pockets of measles as a constant presence.

Meanwhile, we’re still accumulating new outbreaks, some of them in places that researchers predicted were at risk due to low vaccination rates. Portland, Houston, and Kansas City all had small outbreaks and were identified as risky areas in a 2018 PLoS Medicine study. The outbreak in Clark County, Washington, just across the state border from Portland, Oregon, has been the most widely covered. Now the Detroit area is also experiencing a substantial one in precisely the county the paper predicted.

A large chunk of these cases have been within tight-knit communities with low vaccination rates. The outbreak in Washington state originated within a Slavic community, and the two ongoing situations in New York—in Rockland County and Brooklyn—are both largely situated within the Orthodox Jewish groups living in the area. This is true of many of the recent severe measles years. In 2014, more than half of the total cases were from a single outbreak among the Amish in Ohio. A small, concentrated group of Somali-Americans in Minnesota were the epicenter of the main 2017 outbreak, and Orthodox Jews represented many of the 2018 cases.

But there’s also the rising problem of vaccine exemptions. Many states allow parents to cite religious or philosophical objections to keep their children from getting vaccinated, and these lax laws have allowed certain communities to have immunization rates low enough to allow measles to spread. To prevent the virus from hopping between people, 95 percent of the population must be immune. But many states now have kindergarten populations with vaccination rates well below that point, meaning the extremely contagious virus can spread quickly if just one case winds up in the wrong place.

Outbreaks like these often expose people who can’t get vaccinated, whether because they have immune system problems or are simply too young, and it’s these people that public health officials really worry about.

Here are answers to some more questions you’re likely to have as these outbreaks evolve.

Where are these outbreaks?

As of May 14, 23 states had reported measles cases to the Centers for Disease Control in 2019: Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Texas, Tennessee, and Washington. Eight of those—Arizona, Colorado, Oregon, Texas, Michigan, Missouri, Pennsylvania, and Washington—allow philosophical objections to vaccinations and have counties with dangerously low vaccination rates.

Not all of these states have outbreaks—some have isolated cases, which are not uncommon. Only parts of New York, Michigan, New Jersey, California, Georgia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania have ongoing outbreaks, which are defined as three or more cases in a cluster. But already we’ve seen one outbreak spark another. Michigan public health officials confirmed that their outbreak began when a man caught measles in Brooklyn and then traveled to the Detroit area. Washington public health officials report that two patients in its outbreak moved to Georgia.

Most of the other ongoing situations are the result of international travel. Since the virus is no longer endemic to the U.S., this is the primary way that measles outbreaks begin: someone unvaccinated travels and then brings the virus back to the states. And when you have pockets of low vaccination rates, those singular events can spread rapidly.

Many of the measles cases brought into the U.S. annually, for instance, come from the Philippines. There’s currently an ongoing outbreak in the Philippines, where more than 200 people (most of them children) died in January and February out of a total 12,700 cases. That’s quite an increase from last year and, according to Al Jazeera, has largely been blamed on a drop in immunization rates. Health officials in the Philippines say some areas have coverage as low as 30 percent, and the overall rate is already down to 60 percent.

How many people are sick so far?

Here’s the most up-to-date information for each state with an ongoing outbreak (updated May 14):

California: out of 44 total cases this year, 30 have been associated with outbreaks in various counties, though the ongoing situation is mainly in the Butte County area (Sacramento and L.A. are also experiencing smaller outbreaks).

New York: there have been 498 cases in Brooklyn and Queens since October 2018, and 225 in Rockland County in the same period—all have been within the Orthodox Jewish community, where vaccination rates are especially low.

Michigan: 43 people have gotten sick so far, all but one of which can be traced back directly to the outbreak in New York City. State health officials confirmed that a man traveled from the city to Southeast Michigan while contagious, but before he had symptoms.

New Jersey: so far there are 14 cases, 12 of which are associated with the outbreak. That’s on top of the previous outbreak that went on from October 2018 to January 2019, in which 33 people fell ill.

Georgia: six cases in total, three of whom are family members and none of whom had been vaccinated.

Pennsylvania: five cases in Allegheny County, four of whom are related and brought the virus in from out of the country.

Maryland: five cases have been confirmed so far in a cluster, with possible exposures occurring in Pikesville.

Note: the outbreak in the Pacific Northwest ended officially at the end of April with a total of 77 people affected

How did this all start?

For the last twenty-odd years, U.S. measles outbreaks have mostly begun the same way: someone brings in measles from a foreign country and spreads it to unvaccinated Americans.

More broadly, though, this is happening because we haven’t achieved high enough vaccination rates. Though the nationwide vaccination rate is 91.9 percent, there are pockets where the rates dip below that, especially in young children who are most vulnerable to the virus. These pockets allow measles to spread and potentially to jump out into the broader population, exposing people who can’t get the MMR vaccine for medical reasons. Though Washington state legislators just passed a bill banning personal and philosophical exemptions, lawmakers in Arizona are doing precisely the opposite: they’ve introduced multiple bills that would make it even easier to avoid vaccinations. According to CNN, at least 19 other states have tried to introduce similar bills, though that doesn’t necessarily mean that they’ll pass.

Should I be doing anything?

If you or your children haven’t gotten both doses of the MMR vaccine, that should be your top priority. Kids as young as 9 months old can get their first shot, and barring a medical issue (your doctor should know whether or not you have one that precludes you from vaccination) all healthy teenagers and adults can get the shot as well. They only sweeping exception is for people who are currently pregnant.

Some minors have started looking into getting vaccinated without their parents’ permission. In most states, there’s not a lot you can do until you’re 18, as many laws prevent minors from making their own health decisions. But there are 15 states where you can get vaccines without parental consent: Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Delaware, Idaho, Illinois, Kansas, Louisiana, Maine, Massachusetts, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Washington, and West Virginia. If you live in one of those states, you should be able to get a physician to give you a vaccine as long as they deem you mature enough to understand the procedure.

If you live in or near one of the areas affected by outbreaks, you can check the list of potential exposure sites on your state’s department of health website. Washington and Oregon, for instance, have an extensive list that’s constantly being updated. Should you discover that you may have been exposed to measles (or if you think you might have it), the CDC recommends that you immediately call your physician to determine whether you’re immune to the virus. You’re considered immune if you’ve had both MMR doses or if you were born before 1957, since the virus was so widespread until then that virtually all children were exposed. If you were born just after this and got vaccinated in the ’60s or ’70s, you may need to get another shot. We have more info on that here.

If you might not be immune, the CDC asks that you stay away from places where there may be immunocompromised people or those too young to get vaccinated—like schools or hospitals—until your doctor gives you the okay. You should also take particular care to avoid contact with pregnant people and newborns. Some parents with young babies who haven’t gotten vaccinated yet are choosing to stay out of public as much as possible to reduce the risk of exposure.

Bottom line: get vaccinated, and urge others to do the same.

This story is being updated regularly as new cases and information come in.

Note: A previous version of this story, including a chart, cited the cases for 1995 as being 935. There were actually only 309.