Lyft’s braille guide to autonomous tech helps the blind become familiar with robocars

Autonomous vehicles offer a promise of independence.

Last week, the National Federation of the Blind held its annual conference in Las Vegas, and during the event, ride-hailing service Lyft gave brief trips in self-driving cars to around 50 people who are blind or low-vision.

Autonomous vehicles have perception, or vision, systems designed to allow the car to see the real world around them. That way, it can (hopefully) carry out critical driving maneuvers like slamming on the brakes if a pedestrian steps in front of it. A self-driving car transporting a person with limited or no vision is a great example of a controversial technology’s promising uses—a machine that takes the wheel when a human cannot, and a smart intersection of tech and accessibility.

But the tech can remain mysterious, scary, or intimidating to people who haven’t experienced it before (and have different levels of trust in technology). Part of the demystification process involves simply learning how the system works. The self-driving Lyfts in Vegas were operated by a company called Aptiv, and in those vehicles, a person sitting in the back seat can see a screen that shows what the autonomous car’s sensors are seeing. Communication tools like that between the machine and the human’s are an important way to build trust.

“When you’re a sighted person, and you get into the car, you get to actually see what the car is ‘seeing,'” says Marco Salsiccia, a consultant with Lyft and an accessibility specialist who is blind. “You get to see where all the sensors are—you get to visually take in all the information.” But a person who is blind cannot see that screen, of course, nor can they get a visual tour of the sensors on the outside of the vehicle.

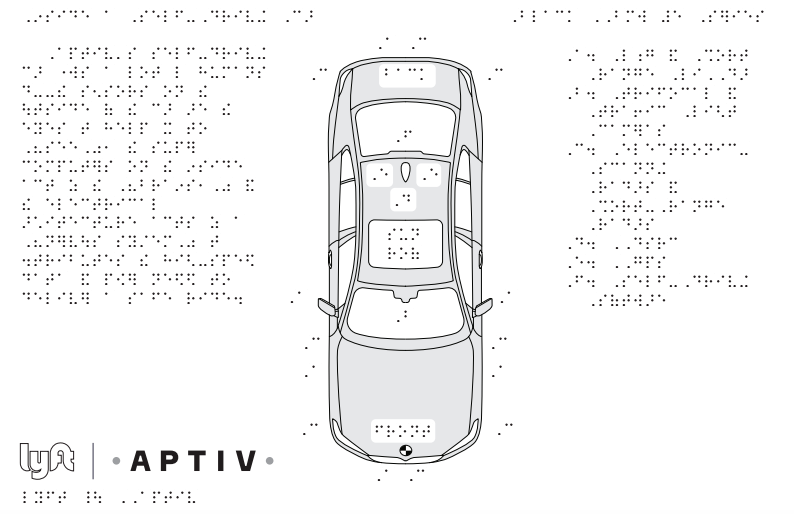

So to make up for that communication gap, Salsiccia, Lyft, and the Lighthouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired in San Francisco’s Media and Accessible Design Lab came up with a paper guide to the vehicles that explains through braille how they work—the document illustrates where the car’s lidar units, cameras, radars, GPS unit and its computer system are located. It explains what all those sensors and other pieces of hardware actually do, and how they work.

After they took a trip in a vehicle, the blind and low-vision riders had the chance to feel the braille guide to the vehicle they had just ridden in; they also got to check out a braille map that illustrated the ride they’d taken. A Lyft spokesperson says that the tactile guide to how a self-driving car works will be left in the autonomous Aptiv cars for blind or low-vision riders who might cruise with them in the future—a guide for how the driving machine sees, readable by touch.

Right now, self-driving cars are parts of fleets operated by companies—Waymo has a self-driving taxi service in the Phoenix, Arizona area, for example. So while autonomous cars aren’t the types of vehicles people can own yet—leaving aside services like Tesla’s Autopilot, which isn’t a full self-driving feature—the concept of self-driving cars holds understandable appeal for the blind community.

“The ultimate idea of the self-driving car, for those of us who are blind and low-vision, is it demonstrates pure mobility and independence,” Salsiccia says. “You have a lot of blind people that drove before they lost their vision—you have a lot of people that just want that experience to be able to do something by and for themselves.”

Ultimately, riding in a self-driving car shouldn’t feel, or be, any different from a vehicle piloted by a responsible human. But that doesn’t detract from just how cool the idea of a short trip down and back down the asphalt in Las Vegas is in an autonomous vehicle. “Just feeling the car changing lanes and negotiating that u-turn—it just feels so natural and smooth,” Salsiccia says.