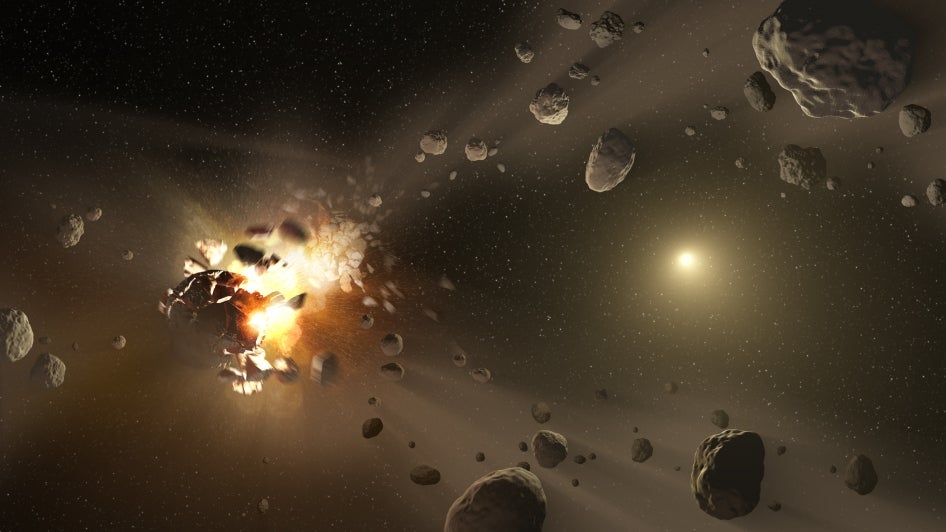

200,000 asteroids trace their origins to just a handful of obliterated parents

And that’s only the inner asteroid belt.

Families can be out there in so many ways, with foibles, feuds, and funny anecdotes about that time Aunt Suzy did that thing. You remember the one. But asteroid families take ‘out there’ and elevate it into outer space.

You might think of asteroids as mindless blobs of rock circling our solar system, and you’d be completely correct. But these chunks of stone have a fascinating origin story—one that scientists here on Earth are still trying to piece together.

In a paper published in Nature Astronomy, researchers found that by looking at the size of the asteroids, in addition to their trajectory around the Sun, they could sort out 85 percent of the asteroids in the inner solar system into about six families. Each family traces its lineage back to a larger parent body (a small planet or planetoid) back in the early days of the solar system.

Back then, the solar system was a much more crowded place, and those parent bodies started getting jostled around, with asteroids and moons and planetesimals slamming into newly-formed planets and each other. The bodies that became the asteroids we see today eventually fragmented into thousands of smaller bits and pieces that honored their parent’s legacy by generally sticking together in their eccentric orbits, even if they didn’t live in the same giant rock orbiting the Sun.

The idea of asteroid families isn’t new. In 1918, a Japanese researcher named Kiyotsugu Hirayama noticed that some asteroids had similar elements to their orbit.

“[Hirayama] noticed that the orbital elements of asteroids—their eccentricity (the deviation from a circle) and their inclination (which is their tilt to the plane of the solar system)—he discovered they were not random. There were some groups of asteroids with the same eccentricity and inclination,” says Stanley Dermott, lead author of the Nature Astronomy paper. Hirayama called these groups of asteroids with similar characteristics ‘families.’

Since then, advances in astronomy have led to the discovery of hundreds of thousands of other asteroids, and new families have emerged. But overall, Hirayama’s idea has held up over the past 100 years—with the exception of a few outliers.

“The work done in seeing if the clustering of orbital elements exist has shown only about half of asteroids appear to be in families. People couldn’t place the other half, so they’re called non-families,” Dermott says. “Our work has shown that this division between family and non-family is probably a false one.”

“What we’ve done is discovered that there’s also a relationship between these orbital elements and the sizes of the asteroids,” Dermott says. He and his colleagues looked at the sizes of asteroids and the distribution of asteroids of different sizes within the inner asteroid belt and were able to bring even more asteroids into the family folds, classifying 85 percent of the asteroids they looked at into about six families, each named after the biggest object in the bunch.

There’s Vesta, Flora, Nysa, Polana, Eulalia, and Hungaria. Probably the best known of these is Vesta, which got a visit from NASA’s Dawn spacecraft in 2011.

The orbits of the asteroids change slightly over time as the gravitational pull of Jupiter or Saturn tugs at the space rocks. Other researchers had analyzed and documented these orbital changes, but Dermott and colleagues looked at how those shifts related to the size of the asteroids.

“We found out that in the inner belt the larger asteroids seem to have a higher inclination than the smaller asteroids. And that’s a very peculiar observation,” Dermott says.

When he took a closer look he noticed that the pattern was consistent in both the family and ‘non-family’ asteroids, suggesting a link between them.

“They must have come from the same families to see the same trends,” Dermott says. What many researchers thought of as ‘non-family’ asteroids were likely once part of these six families—they’d simply become estranged thanks to changes in their orbit that evolved over the past four billion years.

The 200,000 asteroids analyzed by Dermott and colleagues were just a fraction of the 780,292 asteroids identified by NASA so far. The selected asteroids are all in the inner asteroid belt, a region that is closer to Earth and more studied than the middle or outer asteroid belt. There are plans to study the families of the middle and outer asteroid belt in the future.

There’s still plenty to learn about asteroids, and plenty more ways to do it. In addition to statistical analysis like the work done by Dermott, there’s also ongoing analysis of meteorites—bits of asteroid that make it to Earth—and two exciting missions to visit asteroids out on their turf. NASA’s OSIRIS-REx and Japan’s Hayabusa-2 both aim to return samples from asteroids to Earth within the next several years.

“We’ll only get tiny bits of dust,” Dermott says, “But you can do wonders with tiny bits of dust.”