Where Do Geysers On Enceladus Erupt From? Probably A Buried Ocean

Good news for alien hunters

A map of more than 100 geysers on the surface of Saturn’s moon Enceladus has helped scientists determine where those water jets are spouting from—and the results are encouraging for scientists who want to look for life there.

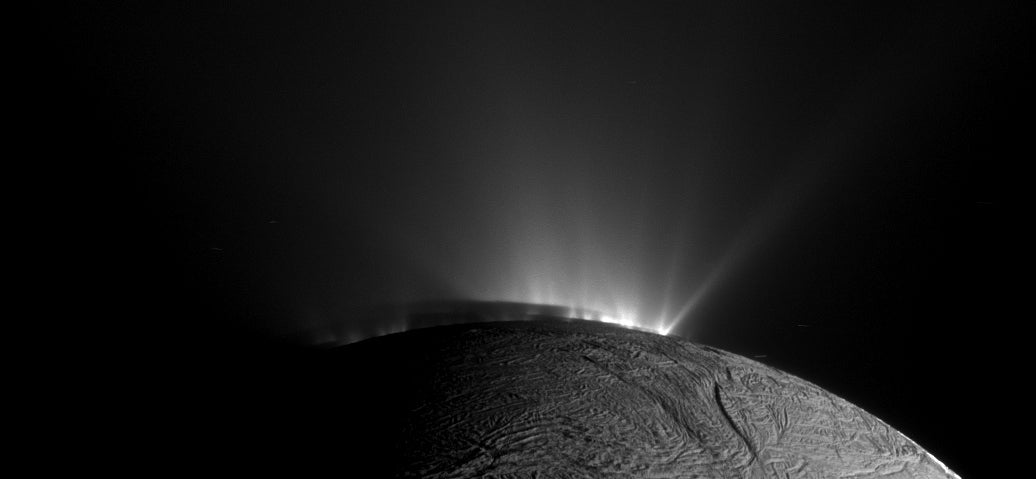

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft first spotted the 125-mile-high geysers erupting from Enceladus’ south pole in 2005. Since then, scientists learned that the geysers contain ice and water vapor (exciting news, since on Earth we find life pretty much everywhere there’s water). The jets burst out of “tiger stripes”, or fractures, that form as Saturn’s gravity deforms the moon’s icy surface.

What has remained a tantalizing mystery is the origin of the geysers. Do they erupt from a subsurface ocean, which is believed to be about six miles deep, buried beneath 25 miles of ice, and potentially capable of sustaining life? Or are they merely a result of frictional heat from the ice fractures rubbing together? The geysers overlap with hotspots on the moon’s surface, but scientists couldn’t tell whether the hotspots cause the geysers or vice versa.

In a paper published today, scientists compared geyser activity with high-resolution heat maps of the moon’s surface. They found that the hotspots were only a few dozen feet across, which is too small for the heat to be caused by the grinding of the 84-mile-long ice fractures. Instead, the scientists think the geysers cause the heat—when the vapor spews out, some of it condenses on the fracture wall and releases heat.

“Once we had these results in hand, we knew right away heat was not causing the geysers, but vice versa,” Carolyn Porco, lead author of the paper, said in a press release. “It also told us the geysers are not a near-surface phenomenon, but have much deeper roots.”

The team has concluded that the geysers must be coming from Enceladus’ inner ocean. That’s good news for scientists who want to search for alien life, because it means that future missions to Enceladus won’t need to drill through 25 miles of ice in order to sample the water below. Instead, a flyby mission could just swoop through the geysers to taste what’s inside the ocean, and see if it may be harboring any simple life forms.