Antibiotics save lives—but misusing them could lead to millions of deaths

According to a new UN report, drug resistance could result in 10 million yearly deaths by 2050.

Overuse and misuse of antimicrobial medicine could cause devastating infectious disease outbreaks in the coming decades, according to a concerning new report from an infectious disease unit within the United Nations. The group—the United Nations Ad hoc Interagency Coordinating Group on Antimicrobial Resistance—calls for “immediate, coordinated, and ambitious action” to avoid this crisis.

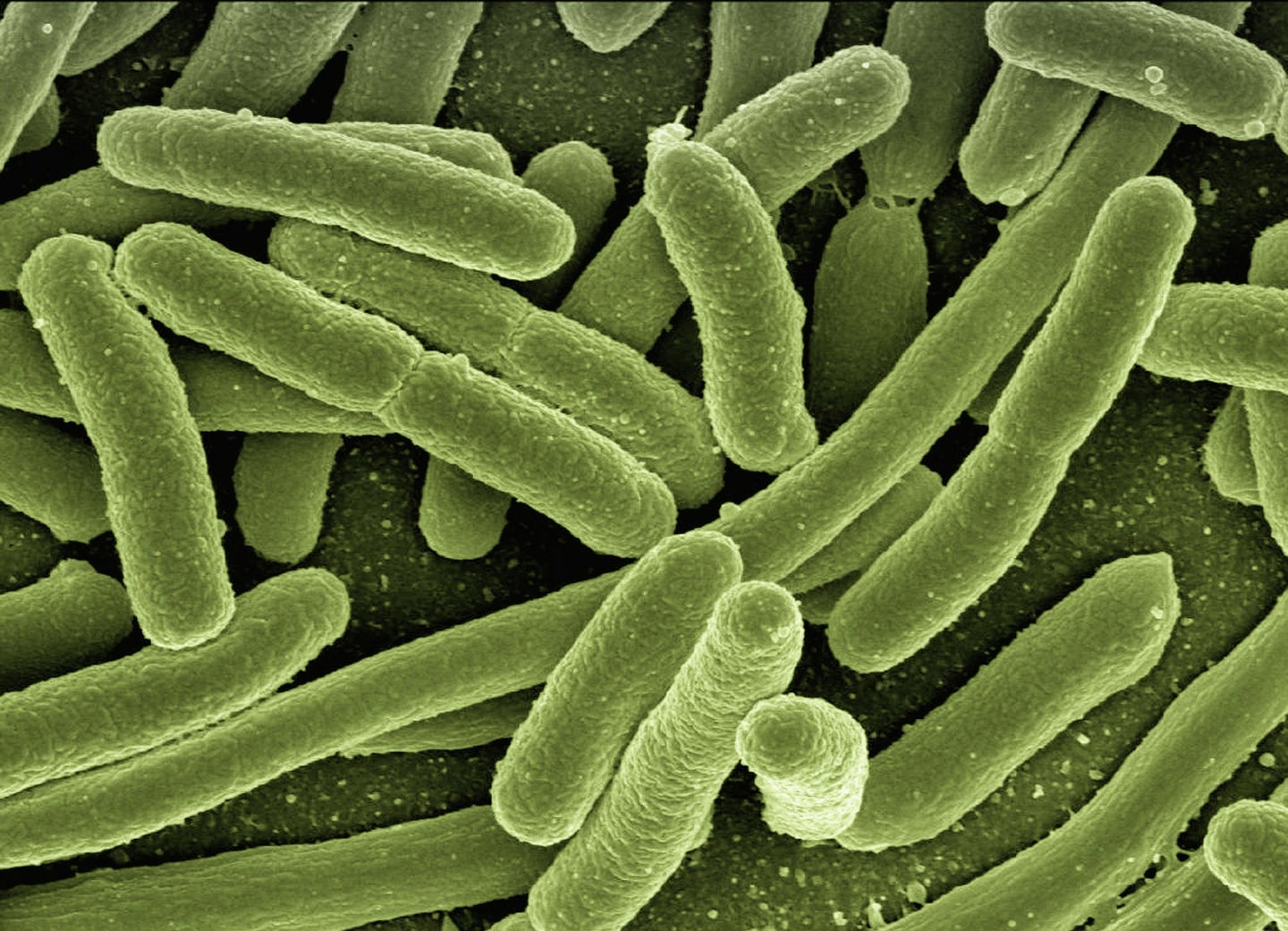

While non-communicable conditions like heart disease and stroke are the greatest killers of humans worldwide, infectious diseases like tuberculosis, MRSA, and malaria are becoming more resistant to the medications used to treat them. The target of mostly effective treatment campaigns over the past century, these ailments have largely been on the decline—but that could change.

Not only can these bacteria, fungi, parasites, and other microorganisms affect otherwise healthy humans, but they’re also a concern for those undergoing medical procedures like organ transplants, chemotherapy, and major surgeries. The report emphasizes that this issue will affect both low- and high-income countries: Infectious diseases are becoming harder to treat, and hospitals are becoming riskier places to pick them up from.

According to the report, around 700,000 people die from drug-resistant diseases each year—that number could skyrocket to 10 million if countries don’t take action.

Those measures include taking a holistic approach to disease management, the report says, tying together environmental, human, and animal health. That would involve countries putting more regulations in place and beefing up their education on the use of antimicrobials as well as investing in more research to create better versions of these medicines, and ending agricultural reliance on antibiotics, too. In short, the UN wants us to stop overusing antimicrobial drugs and to make them better and more equitable when we do use them.

Microbes can naturally become resistant to drugs over time due to genetic mutation—this is similar to why you have to get a new flu vaccine every year. But human practices can accelerate that process by exposing infections to their treatments too often and giving the germs more chances to adapt. Taking antibiotic medication when you have a cold or flu virus, for example, doesn’t do anything to help the infection (antibiotics kill bacteria, not viruses) and instead increases the chance of the antibiotic coming into contact with bacteria—and that microbe mutating as a result.

Another major contributor to antimicrobial resistance is the excessive and unnecessary use of antibiotics in agriculture. In some countries, farmers use as much as 80 percent of all medically-important antimicrobial medications produced to promote growth and prevent disease in animals like chickens, pigs, and cows. This practice is especially popular in Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs), in which too many animals are crammed into small spaces, increasing the risk for the spread of infection. But the World Health Organization says antibiotics shouldn’t be used to prevent infections in farm animals, only to treat existing ones.

In many countries, including the U.S., agriculture is an especially big problem in the war on microbes. America’s livestock farmers use more antibiotics per pound of meat produced than anyone else in the world, and upwards of 60 percent of these drugs target bacteria that affect humans. Further, these practices are mostly unregulated—while the FDA has guidelines on best practices for industrial farmers and antibiotic use, they’re not legally binding.

The report suggests that we’re unsustainably pumping antimicrobial drugs into ourselves, our food system, and our environment. Combined with the fact that research to develop new technologies for treating antimicrobial infections has been slow and sparse, the germs end up evolving faster than we can fight them. If this continues, millions of people around the world could be at risk.

When it comes to the medications we use to treat infectious diseases, the UN’s message is clear: Drug responsibly.