Bush’s Tropical Paradise

The president sets in motion the largest ocean preserve ever—but will industry kill it?

Sea Change

In his eight years as president, George W. Bush has done little to win the hearts of conservationists. Opponents criticize his backing of widespread drilling and mining projects, lax oversight of industrial pollution, and recent attempts to dismantle the 36-year-old Endangered Species Act.

But now, as he’s leaving office, the 43rd president is attempting to “blue” his legacy by granting national-monument status to a string of pristine islands, atolls and coral reefs in the center of the Pacific Ocean.

Even those most critical of Bush’s environmental policies have voiced support for what could be the largest conservation initiative in American history, one that would protect wildlife by completely prohibiting commercial activity.

The Mariana Trench

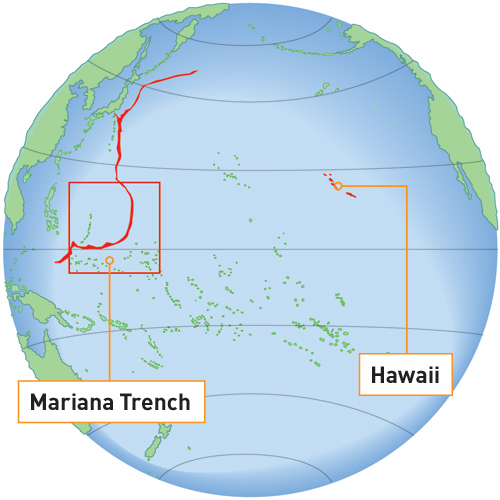

As of press time, government agencies declined to divulge details or a time frame for a decision. They did, however, confirm that the president had requested an assessment on the possibility of increased protection for up to 700,000 square miles of ocean (three times the size of Texas) west of Hawaii, as well as the Northern Mariana Islands and the Mariana Trench, a 6.8-mile chasm that marks the deepest part of the ocean and harbors hundreds of exotic marine species. Many of these islands are already national wildlife refuges, but Bush’s plan could extend the boundary of protection from between 3 and 12 nautical miles offshore to up to 200.

That’s good news for plummeting ocean diversity. The designated area boasts 19 species of whales and dolphins, giant clams, sea turtles, Hawaiian monk seals and 14 million birds, including many of the last albatross and boobies. Endangered and threatened species are rarely found in such profusion elsewhere on the planet. Don Palawski, a Pacific Islands refuge manager with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, says the region is a model of what healthy coral-reef ecosystems should look like and, if well-preserved, could teach us how to better steward damaged reefs closer to civilization.

The proposal would protect coral reefs and other sea life

But how well this “underwater laboratory” is protected will be key to the initiative’s success. Bush has the power to prohibit fishing, deep-sea mining and oil drilling in the area. Without such a ban, environmentalists say, the initiative would amount to a grand but meaningless gesture. For now, there’s almost no fishing, mining or drilling in the central Pacific—it’s too remote to be economically viable, says Joshua Reichert, managing director of the Pew Environment Group, which has been discussing protections with the Bush administration since 2006. But fisheries could target the tuna that migrate through the region or hunt sharks for the lucrative Asian shark-fin trade.

Although public opinion on the few inhabited islands leans in favor of the plan, the Northern Marianas House of Representatives voted against monument designation, citing fear over future fishing restrictions. A similar proposal for islands off North Carolina and in the Gulf of Mexico was dropped last year after vigorous opposition from industrial fishing interests.

Somewhat ironically, Bush’s best ally in this battle may be climate change. With warmer waters and spiking ocean acidity eroding coral reefs, and 90 percent of the world’s predatory fish—such as tuna, sharks and swordfish—eradicated, conservation takes on a new urgency. “It is imperative,” says Lance Morgan, vice president of the Marine Conservation Biology Institute, “to fully protect this monument.”