Your Nose Is Bad At Warming Air

But there are good reasons why humans have longer nasal passages than their relatives

Nose

Like our early human ancestors, modern humans have short, flat faces. And yet, our faces have protruding noses that are packed with more sinuses than those of chimpanzees, our closest ape relatives—a quirk that has puzzled scientists for years. Now to better understand why our nasal cavity is shaped that way, scientists have compared the temperature and humidity of air as it flows through human nasal passages versus those in chimpanzees and macaques. They found that human nasal passages don’t condition air as consistently, and our protruding noses don’t help much. The researchers published their work today in PLOS Computational Biology.

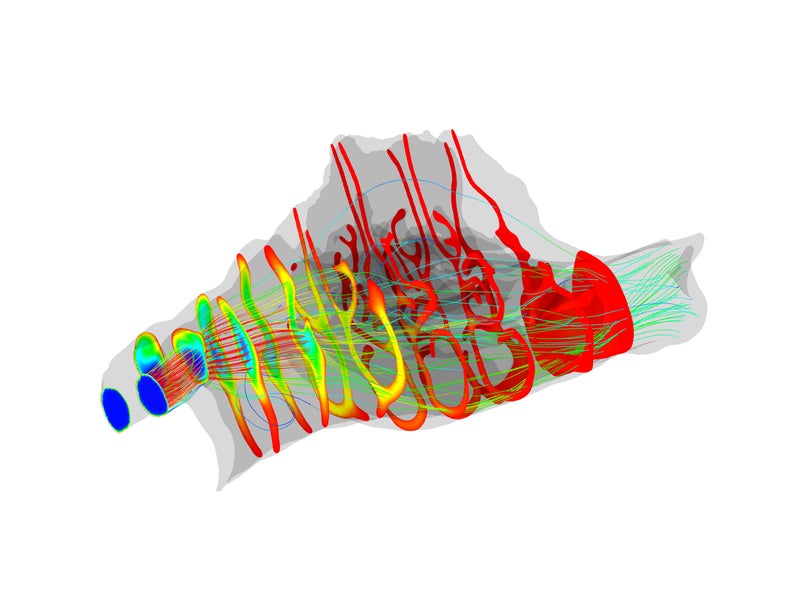

When air is inhaled, it flows past the lining inside the nose and into the sinuses, which warms and humidifies the air. To better understand how these tissues condition the air, the researchers wanted to simulate how air moves through the nasal passages of humans, chimpanzees, and macaques. They took CT scans of four chimpanzees and six macaques, and MRI scans of six humans to capture the dimensions of their nasal passages, from their noses to their sinuses and into the lungs. Then, using simulated outside air that starts under different conditions (warm and wet, cold and dry, hot and dry), they calculated the temperature and humidity of the air as it moved through the different species’ passages.

The researchers found some well-known similarities—that the volume of air and the speed at which it’s inhaled are pretty similar between all three species. But in humans, the air takes a bit more of a detour before going down into the lungs. And while the nasal passages of the chimps and macaques were able to warm and humidify the air to more or less the same point no matter how it started, that process was much less efficient in humans—in each subject, the final conditions were always separated by a few degrees. Air that is too cold or not humid enough can cause damage to the lungs over time. The nose itself, protruding from the face in humans, doesn’t do much to condition the air.

So if noses aren’t good at consistently warming air, why do they look the way they do? The researchers have a couple of theories. The evolution of nose shapes has long been tied to different climates, and the climactic fluctuations that were happening around the time when modern humans evolved would likely have influenced the variation of shapes. Also, humans’ extensive nasal passages give us a greater variety of sounds as air passes through them, which would have paved the way to human speech. This research also sheds light on what the noses of our human ancestors might have looked like as they moved from Africa into Eurasia.