The hellish Venus surface in 5 vintage photos

It's been nearly 40 years since we got a photographic close-up of the volcanic planet.

This post has been updated. It was originally published on January 7, 2015.

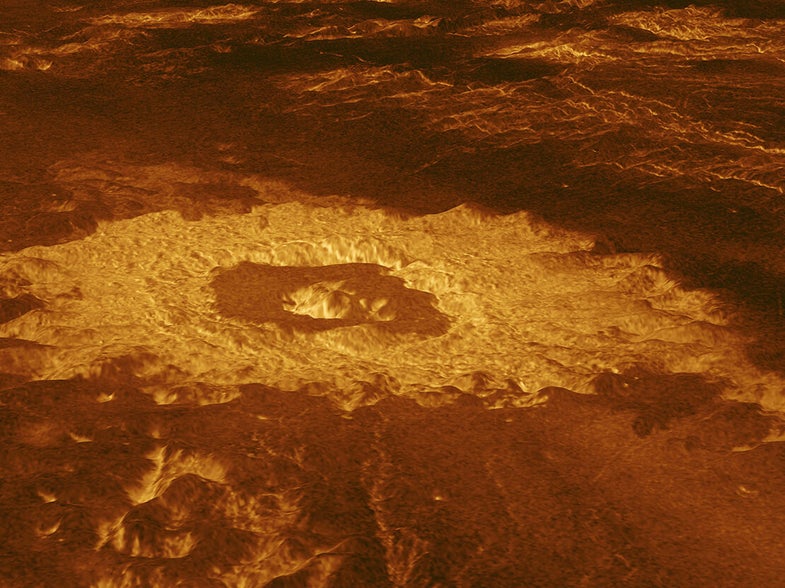

Venera was a series of satellites launched by the Soviet Union in the 1970s and 1980s to study Venus’ environment. It was also the program aimed at returning the first close-ups of the surface of another planet. Over the course of the program, 13 probes successfully reached Venus and transmitted data about our neighbor, eight landed successfully on the surface, and four returned pretty outstanding photos. (The image above is crafted from radar maps, rather than a camera, from the 21st-century NASA Magellan mission.)

Venera 7, the first orbiter spacecraft with a lander in tow, launched on August 17, 1970. After a four month transit to Venus, the landing probe separated the orbiter on December 15 and plunged into Venus’ thick atmosphere. After a period of aerodynamic braking, the upper hatch and heat shield released, exposing the spacecraft the elements and releasing the parachute that slowed the lander. The chute was released six minutes later; Venus’ atmosphere was enough to slow the lander for the final 29 minutes of its descent. It landed successfully, and data was transmitted from the surface for one second before the signal failed—but post-flight analysis of the recorded radio signal revealed that the probe had actually transmitted data for 23 minutes before succumbing to Venus’ environment. Venera 8 followed, launching on March 27, 1972. It reached Venus on July 22, 1972, and once it reached the surface it sent back data for 63 minutes.

[Related: What is Venus made of, and what does that mean for the possibility of life?]

Venera 9, which launched on June 8, 1975, was the first mission to attempt to take pictures of the Venus surface. Though the probe landed in good health on October 22, only one of the lens caps on the two cameras separate. What was planned as a 360-degree panorama around the lander became a 180 degree image. Venera 10 followed in Venera 9’s footsteps, reaching the surface on October 25. Again, only one of the lens caps separated properly returning a 180-degree panoramic image before going silent after 65 minutes on the surface. (Venera 9’s panorama is the upper image and Venera 10’s is the lower image.)

The next two missions were partial successes. Venera 11 landed on December 25, and Venera 12 landed on December 21, both in 1978. But in both cases, the lens cap issue struck again. On these two missions, both lens caps on the cameras failed to separate, so while the landers returned data, neither was able to image the surface.

Venera 13 launched on October 30, 1981, and landed on Venus on March 1, 1982. Once on the surface, the cameras began taking an panorama around the lander. The spacecraft survived for 127 minutes before going silent.

Venera 14 was the last lander mission. It launched on November 4, 1981, and landed on March 5, 1982. The lander survived for 57 minutes before falling silent.

So the images from the surface of Venus might not be as stunning as the vistas we have of Mars, but when you think about the environment those landers had to survive to take those images—temperatures approaching 900 degrees Fahrenheit and an atmospheric pressure 92 times what we feel on Earth—they become pretty incredible. Isn’t it time we devoted more attention to Venus?