Will 2015 Be The Year Our Smartphones Link Up To Our Brains?

A company called Thync thinks so

We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

The Boston office of Thync, its interior walls covered in scribbles of dry-erase marker, exudes the youthful energy of any tech startup. But there’s one noticeable departure from the typical startup visible just as I walk in the front door: a sign notifying study participants to please take a seat: someone will be with them shortly. Over the course of an hour, a handful of these participants, mostly college-aged, cycle through Thync’s offices, where they will fasten electrodes to their heads and become another data point in the company’s growing body of neurological knowledge.

Thync bills itself first and foremost as a neuroscience company. Its sole product—slated for release later this year—is a smartphone-controlled wearable device that will allow the user to actively alter his or her brain’s electrical state through transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). The big idea: give users active influence over their brain chemistries, and therefore their moods, their anxiety, and even their mental productivity—an app that can conjure feeling of calm and tranquility or dial up a user’s attention and focus on demand.

It’s the kind of technology that’s been long promised but never delivered, a melding of consumer electronics and human biology that smacks of fantasy futurism. But nearly 2,000 people have already logged thousands of hours with Thync’s device in scientific trials. That’s what Thync’s founders believe differentiates their company from the many brain-interfacing technologies that have fizzled before it, and why a rotating cast of test subjects–including me–are at Thync’s offices today with small electrodes stuck to our heads. We’re part of the science that Thync’s researchers believe will deliver the first real brain-interfacing consumer product before the end of the year.

“We’re in uncharted territory, it’s a new frontier, and people are going to be skeptical,” says Isy Goldwasser, Thync’s co-founder and CEO. “We want to make sure we have something real. So the company has from it’s outset been about the science, and that’s important.”

Thync’s other co-founder and chief science officer, Jamie Tyler, puts it another way. “This company started as a science experiment,” he says, which is to say it started with a technological outcome rather than a specific product in mind. Goldwasser sought out Tyler, who at the time was doing some envelope-pushing research into ultrasound’s effects on the brain. The duo launched Thync in late 2011 to explore how ultrasound could be used to stimulate certain regions of the brain to produce specific responses, with the ultimate aim of integrating ultrasound into a brain-interfacing device.

Jamie Tyler and Isy Goldwasser

Ultimately the ultrasound efforts foundered, and they turned to tDCS, or transcranial direct current stimulation. The technology, which involves stimulating targeted brain regions with low-current pulses of electricity, was, they concluded, consumer-ready.

Since then, Thync has grown to 20 full-time staff, collected roughly $13 million in venture funding, and produced a closely-guarded prototype of a consumer device that, Tyler says, is easy to use and works for the vast majority of people. With just a couple of electrodes stuck on the temple and at the back of the neck, Thync’s tDCS device delivers specially-designed waveforms of electricity—Thync calls these waveforms “vibes”—to specific regions of the cranium.

A mild shift in the brain’s electric state can reduce stress and anxiety, Tyler says.

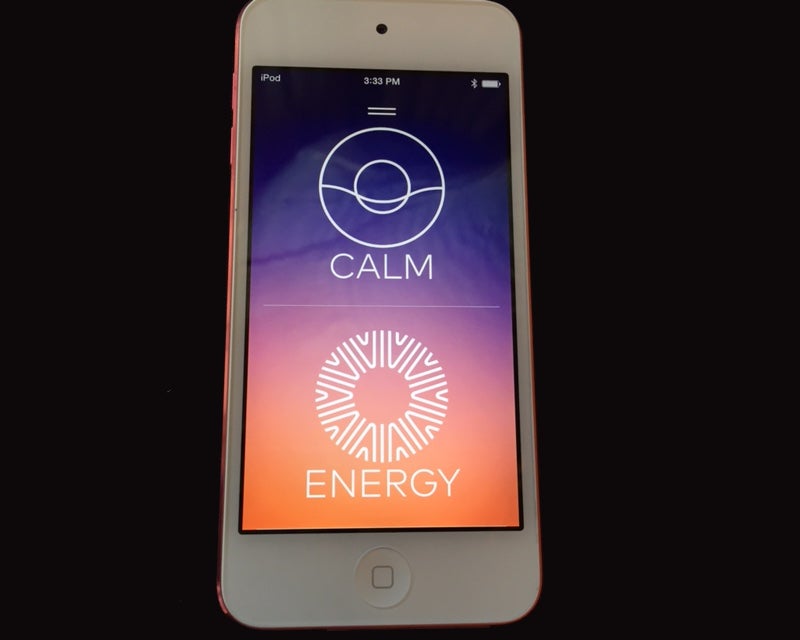

These customized “vibes” are Thync’s secret sauce; the resulting mild shift in the brain’s electric state can reduce stress and anxiety or call up a person’s best stuff on demand, Tyler says. And that’s really just the beginning. Thync plans to launch its app with two vibes, “Calm” and “Energy,” but as the technology (and the science) progresses, more vibes for more feelings could be on the way.

Tyler, Goldwasser, and the rest of the Thync team are adamant that the technology works, and are themselves daily users of the prototype Thync technology. To prove it, they’ve done extensive in-house research (hence the collegiate-types rotating through the front office) as well as contracted a third-party chronic-use study with City College of New York.

Conducted in the lab of Biomedical Engineering Professor Marom Bikson at City College New York, subjects were given tDCS stimulation via Thync’s device, a conventional clinical tDCS device, or sham stimulation—tDCS that wasn’t targeted in any specific way but, in terms of the tactile feel, indistinguishable from real tDCS. One hundred test subjects underwent stimulation as many as five times a day, four times per week, for six weeks running.

“The main outcome was subjective mood,” Bikson says. “This is people themselves reporting how they feel, and whether or not they feel better. In a statistically significant way, we found that subjects receiving real stimulation felt better afterward, and that the relative improvement was larger with the Thync device. In that respect it outperformed conventional tDCS.”

The sham testing conducted via both Bikson’s chronic-use study and Thync’s own 2,000-subject in-house study indicate that the effect is more than mere placebo, Tyler says. Thync’s in-house research team has tested their subjects in every scientifically valid way they can think of, using everything from MRI to heart rate variability to saliva swabs testing for alpha amylase levels (an indicator of stress) to capture before and after physiological snapshots of subjects’ stress levels, anxiety, energy, and attention.

Under the electrodes, the familiar knot of tension between my shoulder blades begins to soften.

It took a year of continuous tweaking for Thync’s vibes to begin consistently beating the sham cohort, but “now the curves are on the other side of the spectrum,” Tyler says, and in almost all cases the Calm Vibe reduces the psychophysiological reaction to stress. Likewise, in testing Thync’s “Energy Vibe,” subjects expressed indicators conventionally associated with increased focus and attention, variously describing the effect as equivalent to a cup of coffee or, at peak, a small dose of Ritalin. The acute effects only last 45 minutes to an hour, but the residual effects of lowering one’s stress or dialing up one’s focus can last much longer.

But all of this data and the underlying science—with the exception of that coming out of Bikson’s lab at City College—is Thync’s own. Its device and research has yet to be peer-reviewed or endorsed by others in the neuroscience community or—critically—the Food and Drug Administration. It’s currently unclear if Thync’s device would require licensing by the FDA as a medical device, but Tyler says the team is working with the agency.

As executive director Sumon Pal fixes two small electrodes to my head he waxes poetic about that science. Writing vibes, he says, is like writing songs. “You figure out the pieces you want, but things change over time.” Over the next 16 minutes, things do change. My head and neck become accustomed to the warm vibrations imparted by the electrodes. My breathing slows noticeably, my thoughts cease their usual ricocheting off one another and zero in on the moment, and the familiar knot of tension between my shoulder blades begins to soften. By the time the Calm Vibe has run its course, the feeling feeling of warm relaxation running through me is somewhat analogous to the sensation one feels after a short bout of meditative yoga—or perhaps a healthy snort of bourbon.

The company is confident that before the end of the year it will be selling a consumer-friendly piece of wearable tech that actively alters users’ biology. Users will enhance their mental state with the swipe of a finger. It’s not science fiction anymore, Tyler says. It’s just science.