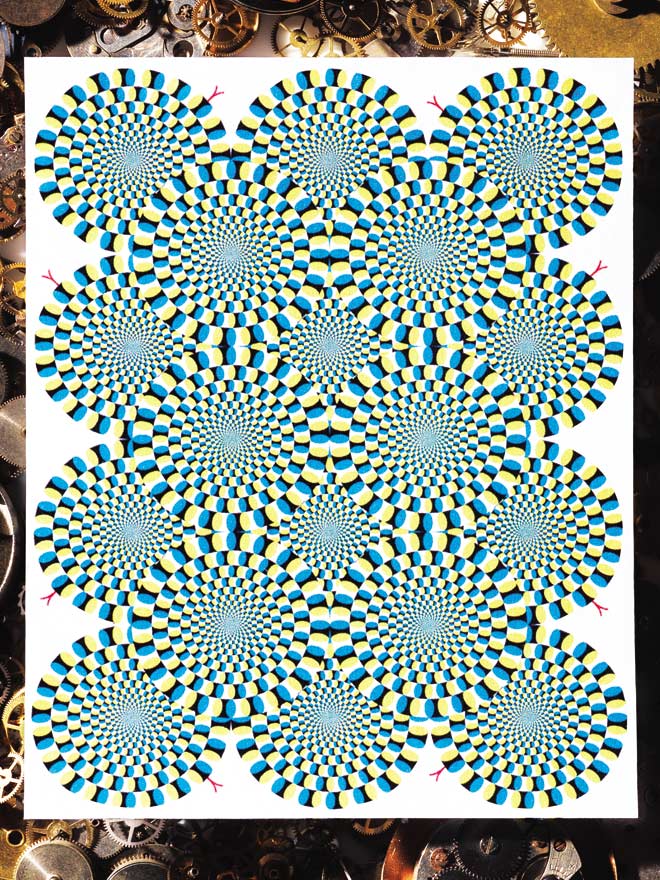

Something in our brain is making these spirals look like they are moving

Snakes on a plane.

Unlike actual snakes, you don’t need to keep a keen eye on the spiraling ones above. In fact, for your sanity, it’s probably best to ignore them: These playful circles stay still when you stare them down one at a time, but spin frustratingly when spied all together.

Akiyoshi Kitaoka, a psychologist at Ritsumeikan University in Kyoto, Japan, made this take on peripheral drift illusions—which make the brain miscast patterns as motion.

Neuroscientists think the shapes mess with the way our brain adapts to disparities in color contrast. When we glance at this image, the blacks and whites cause a bunch of neurons to fire at once. At the same time, the paler blues and yellows trigger a slower, longer-lasting response. Motion-detecting neurons in the visual cortex mistake this difference in firing timing for movement and report that the image is spinning when it’s perfectly stagnant.

Oddly, the effect is fierce in the periphery but muted under direct view. That’s because the eye’s center (the fovea) contains the densest grouping of cones, a type of photoreceptor. This massive cluster of sensory cells lets us see fine details easily, preventing our motion detectors from muddying the works.

You might even be able to fool your cat with it. Some felines, researchers found, display hunting behavior when viewing this illusion.

This article was originally published in the September/October 2017 Mysteries of Time and Space issue of Popular Science.