What It’s Like To Spacewalk For The First Time

An excerpt from Spaceman, a memoir by astronaut Mike Massimino

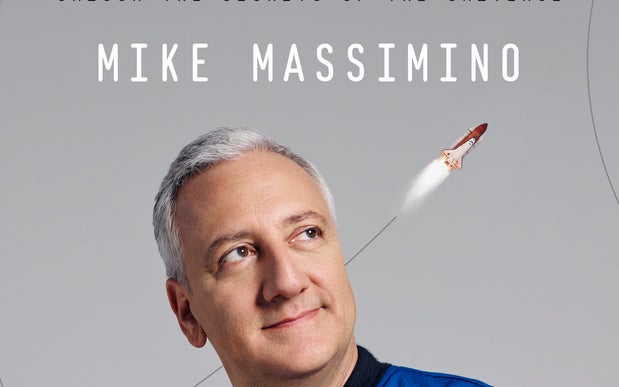

Mike Massimino desperately wanted to become an astronaut from the moment when, as a boy, he watched Neil Armstrong take those famous first steps on the moon. His memoir, Spaceman: An Astronaut’s Unlikely Journey to Unlock the Secrets of the Universe, which came out October 4, poignantly and humorously tells his journey from playing with an astronaut Snoopy toy to donning his own space suit during two shuttle missions to repair the Hubble Space Telescope. In this excerpt, we find Massimino panicking in the shuttle’s air lock as he awaits his very first spacewalk.

When people ask me what it feels like the first time you space-walk, I tell them this: Imagine you’ve been tapped to be the starting pitcher in game seven of the World Series. Fifty thousand screaming fans in the seats, millions of people watching around the world, and you’re in the bullpen waiting to go out. But you’ve never actually played baseball before. You’ve never set foot on a baseball diamond before. You’ve spent time in the batting cages. You’ve run drills and exercises with mock-ups and replicas. You’ve spent months playing MLB on your Sony PlayStation, but you’ve never once set foot on that mound. And guess what? The Series is tied and the whole season is on the line and everyone is banking everything on you. Now go get ’em. That’s how I felt sitting in that airlock. NASA was trusting me to do millions of dollars in repairs to this billion-dollar telescope . . . and until that moment I’d never laid a hand on the actual telescope.

Penguin Random House

It was a moment I’d dreamed of my whole life, something I’d worked toward for years, yet I couldn’t help but worry: What if I was no good at it? What if I didn’t actually enjoy it? What if I hated it?

I watched the clock tick down, anxiously waiting for it to get to zero. Finally it did. We unhooked our suits and we were floating. Scooter [Scott Altman] came by for a handshake and then Digger [Duane Carey] popped in for one last good-bye. Then [John] Grunsfeld floated over to the air-lock’s inner hatch and pushed it closed. He pulled the handle down and spun it shut. It sounded like I was being locked in a prison cell. WHOMP! CHA-CHUNK!

[James] Newman switched our suits over to their own battery power and oxygen. Then he started to depress the airlock. After a final purge of air from the airlock, we were in a complete vacuum. There was no sound. The cha-chunk I heard when they locked us in, I wouldn’t hear that now. I could bang on the shuttle wall with a hammer and I wouldn’t hear that, either; there’s no way for that sound to travel. The only noise I could hear was the sound of my internal cooling fan and some squeaking from moving around inside the space suit. My voice sounded different, too, because the sound wave travels differently through the lower atmospheric pressure. It’s at a lower register. I sounded like I was about to cut a blues album.

At that point we were clear to go. There was nothing left except for Newman to open the outer hatch. Once he did that, I knew the only thing between me and certain death would be this suit I had on.

Newman pulled open the door to the payload bay and pushed the thermal cover aside. Then he went out first to make sure the coast was clear and to secure our safety tethers. When he said, “Okay, you’re clear to come out,” I put my hands on the hatch frame and pulled myself through. I was floating on my back, looking up and out of the payload bay. The first thing I saw was Newman floating above me, hanging out with this grin on his face like Check this out.

Behind his head was Africa.

Hubble is 350 miles above Earth; we need the telescope as far away from the planet as possible in order to have a longer orbit, see more of the sky, and be farther away from the atmospheric effects of Earth. The space station is 250 miles above Earth. From that vantage you can’t fit the whole planet in your field of vision. From Hubble you can see the whole thing. You can see the curvature of the Earth. You can see this gigantic, bright blue marble set against the blackness of space, and it’s the most magnificent and incredible thing you’ve ever seen in your life.

Seeing the Earth framed through the shuttle’s small windows versus seeing it from outside was like the difference between looking at fish in an aquarium versus scuba diving on the Great Barrier Reef. I wasn’t constrained by any frame. The glass of my helmet was polished crystal clear, and every direction I looked, there was nothing around me but the infinity of the universe. I was really out there, floating in it, swimming in it. I felt like a real spaceman.

Adapted from Spaceman: An Astronaut’s Unlikely Journey to Unlock the Secrets of the Universe. Copyright © 2016 by Michael J. Massimino. Published by Crown Archetype, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.