Archive Gallery: Classic Thrill Rides and Carnival Attractions

The Wastebasket of Dizziness, the Corkscrew of Fate, and more amusement park rides and attractions from the pages of PopSci

Our archives are filled with terrifying things — flying tanks, radium faucets, and groundbreaking lobotomy techniques, to name a couple — but few of them are as deliberately scary as the past century’s amusement park rides and attractions. With names like The Wastebasket of Dizziness, The Ring of Death, and the Corkscrew of Fate, how could they not instill terror in even the most seasoned roller coaster enthusiasts?

The early 20th century saw the Golden Age of Roller Coasters, as well as the peak of Coney Island’s popularity. As amusement parks flourished, so did our interest in thrill rides. How did engineers prevent roller coaster cars from toppling off the track? How did the Parachute Jump ensure soft, and not splattered, landings? And why would anybody want to roller skate down a loop-the-loop?

Thrill rides aren’t everyone’s cup of tea, least of all Popular Science writer George Worts, whose article titled “A Dozen Ways of Breaking Your Neck” ascribed people’s love for roller coasters to their suicidal tendencies. Consider his description of the Corkscrew of Fate: “Centrifugal force holds the ball to the rails, and it whirls around and around in the spiral, rolling out at the end against a cushioned bumper, where the occupant emerges, a sadder and wiser, if not a broken, man.

While roller coasters and Rock-O-Planes might be the hallmark of classic amusement parks, they’ve been good at accommodating patrons with mellower tendencies. Coney Island visitors could watch a zeppelin air raid show between thrill rides, while those in need of a little exercise could cart around a gas-powered aluminum horse with wheels.

And if you couldn’t get enough of the amusement park, well, you could always assemble a roller coaster or a merry-go-round out of secondhand lumber and leftover skate wheels. While our backyard carnival DIY projects were geared more toward children than to adults, there’s no better way to cultivate a love for roller coasters in one’s offspring than to build them one yourself.

And the fun continues: earlier this year we looked at the inner workings of the world’s fastest roller coaster.

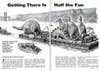

In 1916, the same year that Nathan’s Famous hot dog stand opened on Coney Island, we published an overview of park’s most popular attractions.

“Some of the most successful devices are based on the natural aptitude of many of our supposedly sophisticated city folk to look and act foolish,” we wrote. “Others, designed generally for the younger folk, give a real physical thrill, a ‘shoot the chute’ or near smash-up. Still others are designed to suit the more sober folk, and though thrilling enough for colder temperaments, do not contain that element of apparent danger so delightful to the younger generation.”

The Aerial Night Attack, pictured on the left, was perfect for people who fell into the latter category.. All they needed to do was sit back and watch miniature zeppelins bombard a helpless seaport town. Meanwhile, thrill-seekers could hop on the Auto Maze, which mimicked the experience of reckless driving without the consequence of a car crash.

Not everyone enjoyed Coney Island’s thrill rides, least of all this writer, who declared them a barbarian form of entertainment. “The suicidal instinct must lurk deep within us,” he said. “In its mildest form it displays itself when we march up to a Coney Island neck-breaker and are twisted, turned and hurled by some fiendish contrivance.”

These contrivances included the horseless merry-go-round, a British patent device that challenged passengers to grab a prize while running inside a rapidly whirling wheel. Those who managed to overcome the centrifugal force would likely find at the bottom of a dogpile before they could seize the reward in the device’s center.

Among the the neck-breakers filed away in the patent office, writer George Worts singled out the Corkscrew of Fate as a particularly traumatizing device. Thrill seekers would ride a hollow steel ball down a spiral track and onto a cushion, “where the occupant emerges, a sadder and wiser, if not a broken, man.”

Other infamous rides included the scenic railway, which was essentially a classic wooden roller coaster, as well as a loop the loop you could ride on roller skates. If that didn’t make you dizzy enough, you could ride on the Wastebasket of Dizziness, where cars sped down a spiral track before landing safely on the ground. Nowadays, these rides feel tame compared to the the roller coasters outfitted with facedown drops and 360-degree rotating seats, but you’d be surprised by the number of legitimately scary concepts housed in the patent office. For example, one Belgian device would fling a car, untethered, from an upright steel pole so that it would hurtle through the air and magically land upright on an inclined platform.

Coney Island’s so-called “Horse of Joy” might as well have been called the horse of unnecessary physical exertion, as it required you to run while supporting the weight of the device. And if you were a slow runner, too bad — a small gas motor within the animal’s rear forced you to maintain a certain speed while galloping around the park.

To make his device appear more high-spirited, inventor Otto Fritsche installed the engine’s exhaust pipe in the horse’s ears so that smoke would puff out while you were running. A periscope inside the horse’s head allowed you to navigate the device, while leather straps beneath its neck would ease the burden of carrying it.

Sometimes, it’s more fun to watch daredevils put themselves in danger than it is to risk any yourself. At circuses around the country, spectators would watch stunt cyclists race through thrilling loop the loops unharmed. Like the “Infernal Basket,” in which motorcyclists would zoom around the inside of a circular fence, the loop depended entirely on the concept of centrifugal force. Familiarity with scientific laws not only helped performers come up with daring new stunts, but it eased their anxiety over how things could go wrong.

“Yet it is not reckless bravado that makes the circus daredevil fearless,” said writer and circus performer Hilary Long. “His fearlessness is grounded in the calm confidence that comes with knowledge of physical laws, obedience to them, and firm reliance on their steadfastness.”

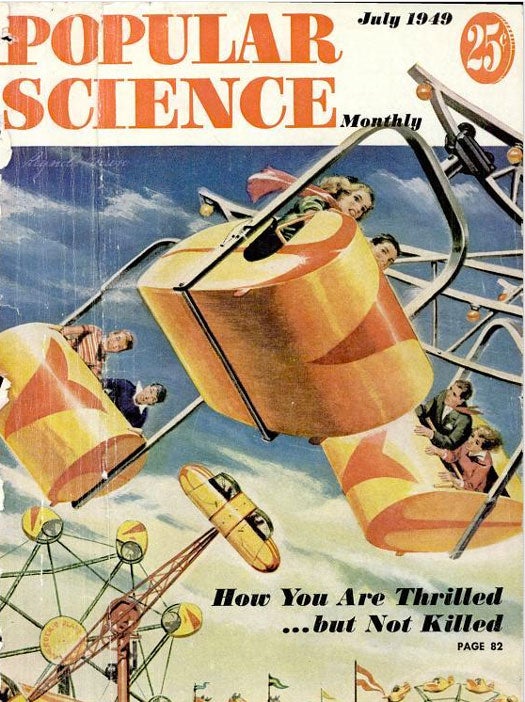

As technology grew more sophisticated, so did the rides at amusement parks. The neck-breaking theoretical rides described in our December 1916 issue not only became real attractions, but they were engineered to ensure safety amidst the illusion of danger. Our favorite rides included the Rock-O-Plane, or a ferris wheel with rotating cars, and Coney Island’s Parachute Jump, which dropped individuals from a 250 foot tower.

While Sinclair Oil’s Dinoland wasn’t a roller coaster or a sideshow, we can’t resist including this exhibition among the attractions in this gallery. After all, there are few thrills like seeing a T-rex and Co. float down the Hudson on their way to the 1964 New York World’s Fair.

To make these dinosaurs, Sinclair commissioned famed animal sculptor Louis Paul Jonas to construct the models as realistically as possible. The first dinosaur, a giant plastic stegosaurus, took two months to make. First, Jonas and his assistant had to create a miniature version of the dinosaur. From that model, they were able to build the full-size version piece by piece. Once the wire-mesh-covered plywood sections were finished, Jonas would coat them in plasticine, steel shims, and air-gunned plaster. Individual parts were then glued together using resin and glass cloth.

The dinosaurs were a huge hit (because who doesn’t love dinos?). You can find the tyrannosaurus and the brontosaurus on display today at the Dinosaur Valley State Park near Glen Rose, Texas.

Can’t get enough of the amusement park? Build a backyard-sized ride yourself. Take this homemade flying merry-go-round, which was built for two English children by their father in the late 1930s. A central pole driven into the concrete held up the two-person gondola, which was driven forward by a one-horsepower gasoline engine that spun a 23-inch wooden propeller.

Let’s go back to 1917. While Coney Island was at its peak, not everybody had easy access to the resort, hence the idea of building an amusement park in one’s own neighborhood. Two young men from South Andover, Massachusetts, spent just 50 cents building this rickety merry-go-round out of oak saplings from nearby woods. For one cent, children and adults could enjoy an eight minute ride powered by the builders themselves, who rotated the carousel with their bare arms.

Sure, it wasn’t exactly a thrilling ride, but patrons blamed that on the merry-go-round’s lack of music rather than on its slow speed. Nor were they satisfied with a whistling quartet and a harmonica player, which led the promoters to consider investing their profits into a phonograph or a hand organ.

Finally, we present the merriest-looking homemade carnival of them all. This backyard extravaganza could be cheaply made with secondhand lumber and various spare materials, like garden hose, a rubber mat, and skate wheels.

The carnival pictured here included four play sets: the miniature roller coaster, the high-boy seesaw, the dos-a-dos swing, and the leg-powered merry-go-round, where some unfortunate child would have to spin the platform while his playmates enjoyed the ride.