Virtual Therapists: The Avatar Will See You Now

Addiction therapists turn to Second Life for help reaching patients

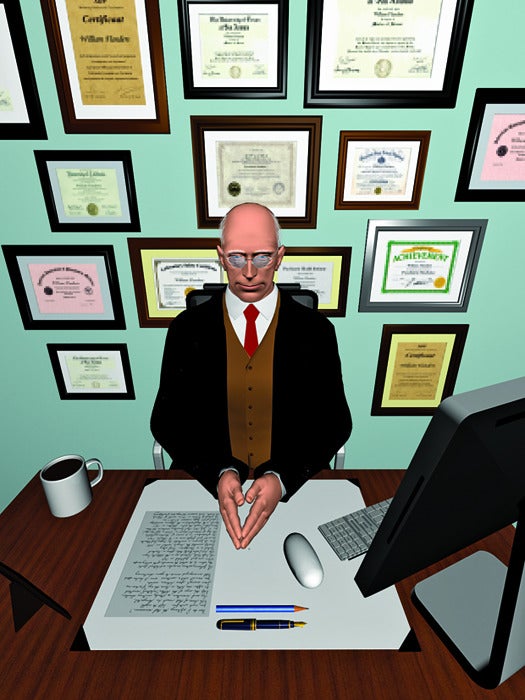

Therapist Brenda Bryan asks everyone in her anger-management group to teleport to a volcano. She explains that the volcano is a reminder that emotional eruptions have fallout. Bryan isn’t your typical therapist. She’s a virtual-world therapist practicing at Preferred Family Healthcare Center in Kirksville, Missouri. So-called avatar therapy transplants standard counseling into virtual settings, in this case, private scenes custom-built using code from Second Life, the online multiplayer game. Avatar therapy has been gaining popularity and credibility recently, with several hundred patients now seeing virtual counselors.

Early research suggests that patients are more likely to show up for virtual therapy sessions than real-world ones. Preferred Family Healthcare is about two years into a three-year study following 70 adolescents with substance-abuse problems. So far, 95 percent of those in Bryan’s virtual-world program have completed or are attending their sessions, versus only 37 percent of patients being treated face-to-face. Previous studies show that attending counseling can greatly reduce the risk of relapse. Researchers cite convenience and less social anxiety as possible explanations for the encouraging results.

“Our virtual clients attend four times as many therapy sessions as people do in real life,” says Dick Dillon, a senior vice president at the center who initiated the research. “We find that people spend more time in session if they don’t have to spend time getting there.” Virtual treatment could expand access to care for people who travel frequently, live in rural areas, or have physical disabilities that prevent them from maintaining a regular therapy schedule.

Some conditions are less amenable to this treatment, however. For example, people suffering from disorders that make it difficult to tell reality from fantasy might not be good candidates.

The virtual setting presents challenges even for treating ideal patients. Dillon and Bryan admit that treating an avatar can be difficult because you can’t read body language or hear someone’s tone of voice. But they say that, overall, patients’ increased openness improves progress. “In virtual therapy I’m comfortable. I can let things out that I can’t normally say in real-life therapy,” says Ginnie Murphy, one of Bryan’s patients. “I probably would have relapsed if I hadn’t had this to keep me stable.”