Darwin Wasn’t A Complete Chauvinist After All

The man who once called having a wife "better than a dog, anyhow" expressed far more egalitarian views in his private letters.

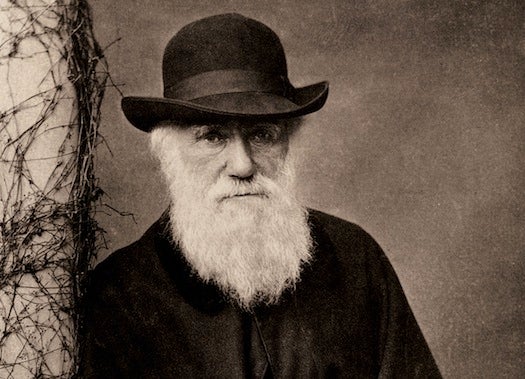

The annals of scientific history are filled with brilliant men who, when push came to shove, weren’t exactly super nice guys. Renown evolutionary theorist Charles Darwin, though, may have gotten more of a bad rap when it comes to his views on women than he rightly deserves.

Historians have long thought of Darwin as a pretty typical man of his time–a Victorian conservative who once wrote that having a wife would be “better than a dog, anyhow,” and in his writing “cast women as deficient in arenas ‘requiring deep thought, reason, or imagination‘”–but his private letters to women, published through the Darwin Correspondence Project, tell a slightly more nuanced story of the scientist’s views on gender.

Previously unpublished letters between Darwin and various women, like the naturalist Mary Treat and suffragette Lydia Becker, show that “his views on gender were a lot more complex than has been acknowledged in the past,” according to Philippa Hardman, leader of the Darwin and Gender project. “He was very comfortable collaborating with women like Treat and Becker and encouraged their scientific work wherever possible.”

The same scientist who wrote publicly that sexual selection made men “more courageous, pugnacious and energetic than woman [with] a more inventive genius” also corresponded regularly with suffragettes and lent a professional hand to the relatively few female scientists around at the time. He encouraged Treat to publish her research on butterflies in scientific journals, and wrote in other letters that women should not be excluded from scientific education.

“There are a number of reasons why Darwin may not have openly expressed his attitudes towards gender equality in public,” Hardman said in a statement. “[Philosopher John Stuart] Mill, following The Subjection Of Women, was openly ridiculed as ‘feminine’–not a portrayal that Darwin needed, given the masculinity associated with academic science at the time. It is also possible that as the proponent of controversial scientific views, he simply felt that further public wrangling on the question of women’s rights was something that he could ill afford.”

He wasn’t a feminist by any means, but at least we can be a little less disappointed in him.