Scientists Implant Monkeys’ Cells Back Into Their Own Brains

The research is a step along the way to personalized stem cell therapies.

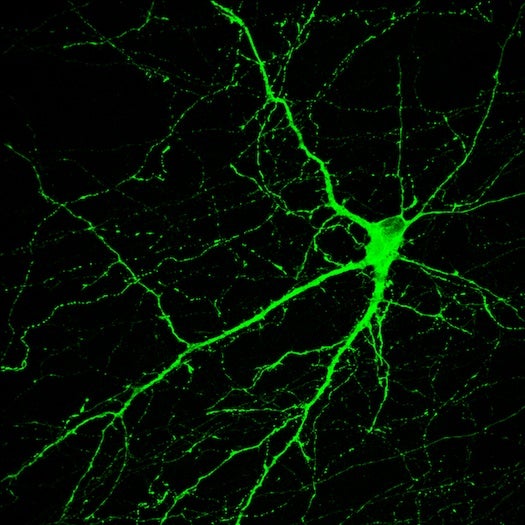

Scientists have taken cells from rhesus monkeys’ skin, turned them into neural cells, then implanted them successfully into the monkeys’ brains. After six months, the transplanted cells showed no scarring and looked healthy and normal—except that they glowed green, a characteristic the scientists added to the cells so they could find the cells later.

The feat is a basic step toward personalized stem cell therapies, in which people might get treated for diseases using their own healthy cells. Of course, a study in monkeys—and one that didn’t cure any disease—is a long way from something your doctor could order. But that’s the eventual aim of studies like this.

The research team, from the University of Wisconsin in Madison, first took skin samples from three rhesus monkeys. They used the famed Yamanaka cocktail to transform those skin cells into pluripotent stem cells, a kind of “blank slate” cell that’s able to develop into any type of cell in the body. It was just the kind of experiment that Popular Science predicted would take off in 2013.

After making stem cells from skin cells, the Wisconsin team coaxed the stem cells into becoming something completely different: early-stage neural cells. At this point, the researchers implanted the cells back into the monkeys, in which they had artificially induced a Parkinson’s-like disorder.

Once inside the monkey brains, the neural cells finished their maturation, got great jobs and their own apartments… I mean, they turned into specialized brain cells called neurons, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. They didn’t die, get rejected by the monkeys’ brains as foreign, or appear cancerous, all of which have happened in some previous stem cell implant studies.

Although the new brain cells settled well into the monkeys’ brains, there weren’t enough of them to improve the monkeys’ Parkinson’s symptoms. The researchers will still have to see if they can implant cells that actually help with symptoms. And they’ll need to keep checking on the monkeys’ brains in the months and years to come, to make sure the implants don’t cause problems later on.

The Wisconsin team published their work today in the journal Cell Reports.