Using Magnets and Stink Bombs to Keep Sharks at Bay

In 2005, Eric Stroud, the managing partner of Shark Defense, a New Jersey company that specializes in shark-repelling technologies, happened...

In 2005, Eric Stroud, the managing partner of Shark Defense, a New Jersey company that specializes in shark-repelling technologies, happened to be carrying a rare-earth magnet as he passed a tank full of sharks. The sharks fled, and Stroud took note. After further tests, Stroud and his colleagues found that sharks that came within 20 inches of rare-earth magnets similar to the one he had been carrying would consistently swim away.

The discovery earned Shark Defense $25,000 from the World Wildlife Fund’s annual International Smart Gear Competition, which rewards inventors who develop new methods to keep animals from getting tangled in commercial fishing lines. Shark Defense is now investigating ways to embed the metals in nets. And Stroud says the same metals, worn as an anklet, could act as a personal shark deterrent.

![Eric Stroud [right] and a colleague apply a chemical repellent based on the smell of rotting sharks to a lemon shark at the Bahamas' Bimini Biological Field Station.](https://www.popsci.com/uploads/2019/03/18/HAJCOXQO3K57TLPJYCWIAO3JT4.jpg?auto=webp&optimize=high&width=100)

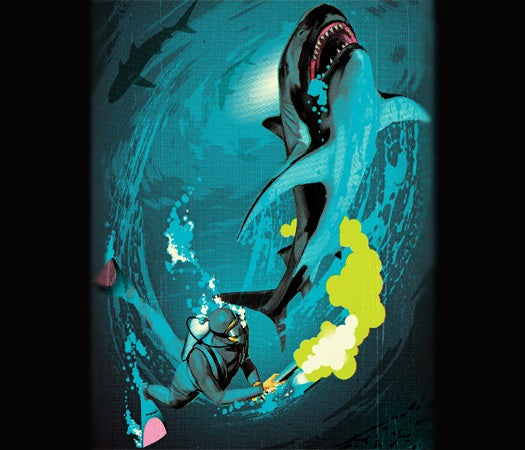

Field Test

The company is also working on a chemical repellent, a slightly sweet-smelling combination of a dozen compounds that mimics the scent of rotting shark. Patrick Rice, the senior marine biologist at Shark Defense, has developed the repellent in several forms: as a pressurized can of aerosol spray that can create a 50-milliliter cloud and is popular with spear fishers, a pouch that bursts underwater to quickly clear an area, and a gel that can be injected into bait to keep sharks from getting hooked. The chemical repellent is less expensive than rare-earth magnets. Still, Rice says, “just like anything else, nothing’s 100 percent effective. If sharks are in a frenzied state, if they’re hungry enough, they’ll start eating.”

Adapted from Juliet Eilperin’s book, Demon Fish: Travels through the Hidden World of Sharks.