With Modified Jet Fuel, Planes Can’t Explode

Coming soon to your local airport

The four planes chosen by the September 11 terrorists were chosen for a reason. All four flights were traveling across the continent loaded down with huge quantities of jet fuel, the ignition source for the horrible tragedies that took place that day at the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and at the crash site of Flight 93 in Pennsylvania.

In 2002, after the attacks, Caltech scientist, Julia Kornfield and colleagues began working on a polymer that could prevent jet fuel from being used as an explosive weapon. Their results are published in this week’s issue of Science. Kornfield’s team, including Ming-Hsin “Jeremy” Wei, one of the first authors of the paper, created a polymer, a large molecule, called a megasupramolecule that can link together with other megasupramolecules to form massive chains.

The megasupramolecules act a little bit like chains with tiny bits of velcro at the end of each one. They can break apart, and then automatically link back together. Watch Kornfield’s explanation of how megasupramolecules work:

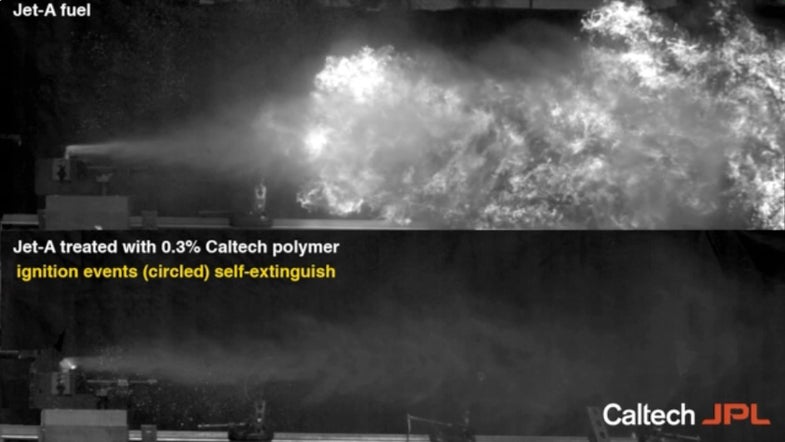

When mixed in with jet fuel, the megasupramolecules help the fuel flow more easily through the engine, and, in crash situations, prevent the fuel from “misting”, or turning into tiny droplets. Misting is fine during normal engine operation, but in a crash the sudden dispersal of fuel over a wide area can make it explosive when it meets a heat source.

“Above all,” Kornfield said in a press release, “We hope these new polymers will save lives and minimize burns that result from post-impact fuel fires.”

So far, it has only been tested in a lab, but initial results are promising. In addition to inhibiting explosions, fuel with the additive functions act just like normal fuel in an engine, meaning airlines wouldn’t have to make additional technical changes to their aircraft. And unlike many scientific ventures, this one might not take long to go from the laboratory to the real world.

“Looking to the future, if you want to use this additive in thousands of gallons of jet fuel, diesel, or oil, you need a process to mass-produce it,” Wei said in a press release. “That is why my goal is to develop a reactor that will continuously produce the polymer—and I plan to achieve it less than a year from now.”

See the test in action here: