Old books actually smell like chocolate and coffee

Sniffing out literary smells

What does a book smell like? Freshly printed books might smell of paper and ink, but older books have a sweet, musky smell that wafts into a book-lovers nose and lingers.

And apparently, it reminds a lot of people of chocolate.

In a study published Thursday in Heritage Science, researchers at the University College London’s Institute for Sustainable Heritage examined the smell of books and libraries, putting together a classification scheme that could help characterize the scents of the past—and maybe even diagnose deteriorating books before damage gets out of control.

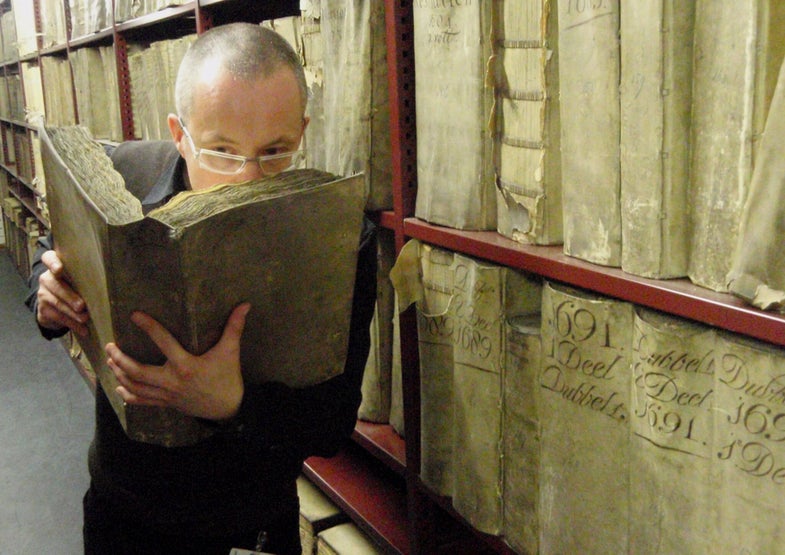

It started a few years ago when chemist Matija Strlič noticed paper conservators stopping to smell the pages of works they were studying. When he asked them why, the researchers said they could tell a lot about the type of materials used in the books by the smell. Strlič—who was also trained as a conservator—was intrigued, and started looking for a way to quantify those odors.

“I thought, surely we can develop some scientific techniques that are more accurate than the human nose,” Strlič says.

Materials like books often release small amounts of volatile organic compounds (or VOC’s) into the air. Our noses pick up those chemical signatures and our brains interpret them as smells.

Those compounds can also be detected by sensors—the same kinds of mechanical sensors used by governments to sniff out drugs or explosives. But in this case, they detected tiny variations in the chemical compositions of very old books. After taking a sample and running it through a gas chromatograph/mass spectrometer combination, Strlič and colleagues were able to identify key smell components in the books.

Strlič partnered with heritage scientist Cecilia Bembibre to start looking not only at the chemical traces of the books, but also at how the smells affected the people that were smelling them.

Bembibre, the corresponding author on the paper, and Strlič partnered with the U.K.’s leading conservation organization, the National Trust, to set up an experiment where visitors to Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery were participated in a test of unlabeled (and concealed) smells. This is where the vast majority of the 79 people interviewed identified old books as smelling kind of like chocolate.

The fact that the participants named chocolate wasn’t surprising to the researchers, though the frequency that they identified chocolate and coffee with eau de book was.

“You tend to use familiar associations to describe smells when they are unlabelled,” Bembibre says. “And also, the VOC’s of chocolate and coffee seem to be very similar to that of books. But it was still surprising to see that reference come up again and again.”

Bembibre also tested what people thought of the smell of the library at St. Paul’s Cathedral, London, where the researchers gathered many VOC samples. The smells recorded there were as a whole described by participants as woody and smoky more than chocolatey, probably because they were able to see the magnificent wooden surroundings. The library was chosen for a reason; the smell in that library is so famed that it often gets mentioned in guest books, and the curator insists that any conservation methods must preserve the distinct smell.

Currently, there is very little precedent for preserving smells in conservation efforts, but that’s something that Bembibre and Strlič would like to change. While most historical exhibitions introduce people to an idea or concept visually, smell also plays a very powerful role in people’s experiences.

“Our sense of smell is very close to the memory center in the human brain, and therefore we very often associate memories with certain smells very powerfully and very strongly,” Strlič says. “Very often smell triggers old memories that we otherwise couldn’t trigger. It is one of the reasons smell plays such an important role in how we experience heritage.”

While conducting the experiments, Bembibre developed a “historic paper odor wheel” which she hopes will help other researchers and libraries characterize the smells coming off the books more easily. Matching up what their nose knows with specific chemical names might tell them something about the composition of what they’re smelling. “You can go from the smell to the compound or the compound to the smell,” Bembibre says.

The researchers hope that it can show people involved in conservation and historical work how smell might contribute to a visitor’s experience.

“I think we might be looking at multi-sensory experience in museums or galleries in the future,” Strlič says.

There are plans to expand the work beyond books to look at how different objects at National Trust properties smell, and to gather suggestions of smells that the community would like to protect for the future—much in the same way that buildings are preserved today.

“As a society living at this point in time, which smells do we want our kids to inherit?” Bembibre says.