NASA’s (Un)Censored Moonwalkers

A big part of going to the Moon was selling the program to the public. Not only was it important...

A big part of going to the Moon was selling the program to the public. Not only was it important for NASA to gain support for the Apollo program, the agency stood to gain nothing by misrepresenting its missions to the taxpayers who were footing the bill. Part of this marketing strategy was transparency, including public release of unedited mission transcripts, a transparency for which we can thank Paul Haney.

Haney during Gemini VII

Meet Paul Haney

Paul Haney was a journalist with the D.C. Evening Star when he joined NASA during Christmas week in 1958. There wasn’t a whole lot going on at the agency at the time. It was still getting its bearings, so Haney and his four colleagues in the public information office spent more time deciding how to publicize spaceflight than actually publicizing spaceflight.

At the time, open communications surround rocket launches and tests was uncommon.Both the Army and the Air Force ascribed to a “fire in the tail” protocol that dictated nothing be said publicly about the launch until after lift-off — literally when fire was coming out of the tail of the rocket. And even then public statements were limited to prepared statements that became completely irrelevant if a test launch turned sour. As Haney described it, “you just looked like a goddamned idiot, particularly with television that would set up outside the Cape.” Not to mention, an exploding rocket wasn’t easy to hide.

It was Haney who helped push NASA away from the “fire in the tail” approach. After his promotion to Director of the News Division in 1960, he argued to have every mission broadcast live in realtime and that every mission transcript released post-flight. The idea gained no traction.

Haney pitched the idea of realtime mission broadcasts again in 1963. By then, James Webb had replaced T. Keith Glennan as NASA Administrator, and though Webb was no more interested in Haney’s idea of open public communication, he didn’t say no. Instead, he told Haney to take the idea to the White House.

So Haney did, bringing his case to President Kennedy’s Press Secretary Pierre Salinger. Sitting in a motel in Florida one day, Haney got a call from Kennedy’s office. It was Salinger, who put a question to Haney about the Mercury escape tower. Haney had just been reading about the system so had figures about its success rate on hand and could readily answer Salinger’s question. The Press Secretary told the NASA News Director, “the President says go ahead. Give it a go. See if it works.”

Haney was thrilled. “I remember throwing that goddamn telephone up as high as I could, and it hit the ceiling and double-dribbled off.” A phone call had effectively started NASA’s Public Information Program.

But transparency didn’t come without a fight. Some astronauts took issue with Haney’s feeling that the transcripts be released without editing, fearing it would damage their public images.

Haney, second from left.

Marketing for the Moon

David Meerman Scott and Richard Jurek recently published “Marketing the Moon,” which goes into great detail about the public relations aspect of the early space program. And one of the more incredible artifacts they’ve found and included in the book gives some really interesting insight into the NASA public affair’s fight with the astronauts over transparency in post-mission material: a letter from Paul Haney with annotations from Alan Shepard.

Haney’s letter clarifies why it is in NASA’s best interest to present the missions exactly as they happened, including astronauts’ personal and professional utterances. “I contend that the slightest editing, censoring, massaging or whatever of the released transcript will not help generations yet unborn to understand what went on… Our literature today is certainly spicey [sic] enough to accept an occasional god-damn or worse. The public at large doesn’t think of our space pilots as altar boys. Certainly the pilots themselves shouldn’t entertain any such grandiose self-appraisal.”

Shepard disagreed, and made some choice comments in the margin of Haney’s letter. Notably, the astronaut challenged then publicity officer: “Would you like publicly review some of your own thoughts and problems?”

Tensions between the Public Affairs Office and the Astronaut Office persisted, but Haney won in the end. Sort of. The mission transcripts were released to the public, the Gemini mission transcripts released with a longer delay after each mission than those from Apollo flights. But only some were released in full, and they were ever so slightly edited.

As missions got longer and more complicated, the amount of material each generated increased. By the time Apollo flew to the Moon, each mission was spawning up to four transcripts: one from the public affairs office, the main air-to-ground transcript from the spacecraft, and transcripts recorded inside both the command-service module and the lunar module. The air to ground transcripts were released almost immediately following the mission while the spacecraft transcripts were classified for 12 years; there could have been discussions of systems NASA didn’t want leaving the country.

These spacecraft transcripts often captured some of the crews’ more “colourful” moments. On their way to the Moon, Conrad made the statement to someone on board: “You’ve got to shit, huh? That figures… I wish I could shit; I’d feel a lot better about it. I don’t – have the slightest inclination, but I just know what’s going to happen. It’s going to be the first shit on the lunar surface.”

But every once in a while something “colourful” slipped out over a public channel and NASA did do a little censoring.

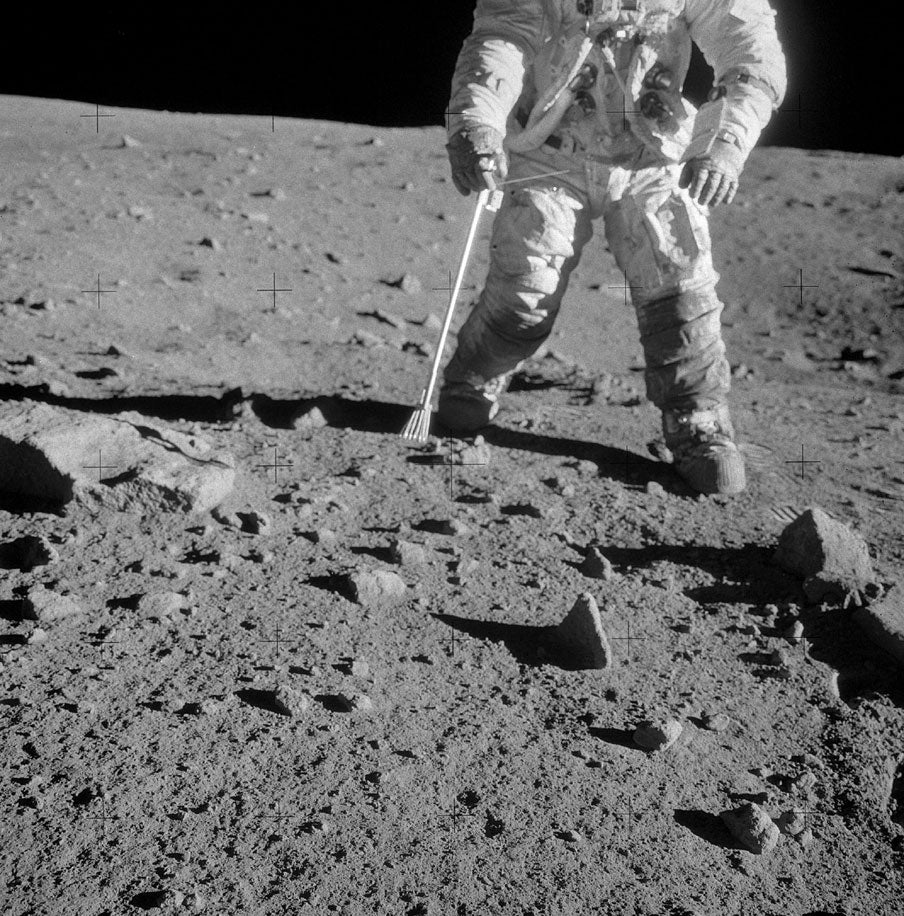

Apollo 16’s John Young

Apollo 16’s Flatulence

During Apollo 15, the crew experienced irregular heart beats that the flight surgeon determined were related to a potassium deficiency. To eliminate the problem, the Apollo 16 crew went to the Moon with fruit and potassium-fortified fruit drinks. While padding around the Moon, Commander John Young shared with Lunar Module Pilot Charlie Duke an unfortunate side effect of this diet, and he didn’t realize the mic was broadcasting the comment to Earth.

*Young: I have the farts, again. I got them again, Charlie. I don’t know what the hell gives them to me. Certainly not…I think it’s acid stomach. I really do.

Duke: It probably is.

Young: (Laughing) I mean, I haven’t eaten this much citrus fruit in 20 years! And I’ll tell you one thing, in another 12 fucking days, I ain’t never eating any more. And if they offer to sup(plement) me potassium with my breakfast, I’m going to throw up! (Pause) I like an occasional orange. Really do. (Laughs) But I’ll be durned if I’m going to be buried in oranges.*

NASA didn’t remove the exchange, but public affairs did clean it up a little. When the transcript was released, the word “farts” was replaced by “gas,” and the word “fucking” was removed entirely.

Luckily, audio records exist and more recent transcriptions include the more colourful language. It’s the only way those of us in the “generations yet unborn” Haney referred to in that letter to Shepard can really grasp the humanity that was part of going to the Moon. Because going to the Moon was human, and that humanity is wonderful. And nobody’s perfect.

*If you’re interested in the public affairs side of the Apollo era, I’d highly recommend “Marketing the Moon.” It dives into one of the least often discussed but vitally important aspects of bringing a lunar mission from concept to reality. Thanks to David Woods, Eric Jones, and everyone who has brought the real words from the Moon to the public through the Apollo Lunar Surface Journal, too!

Sources: JSC Oral History with Paul Haney; NASA; “Marketing the Moon” by Meerman Scott and Jurek.*