This is the most powerful moment in Olympic sport

The ideal form, equipment, and conditions for the first bobsled push.

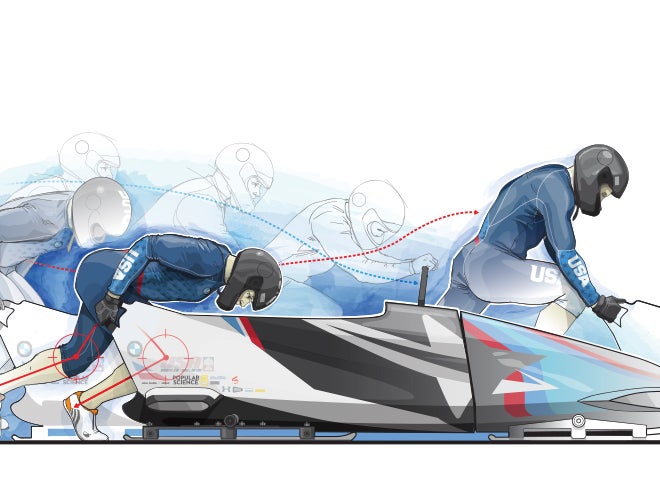

Leg Power

1. On track

Picture a bobsled course as three sections: a 49-foot segment where athletes get their sleigh moving ahead of the starting line; a 65-to 100-foot portion they use to build up speed after the clock starts; and the remaining 4,000 or so feet down which they ride, twisting and turning, to the finish line. The first few runs of the day are always faster: Each one creates more friction-increasing ruts, upping times.

2. Muscleman

A two-person bobsled team includes a pilot, who steers the sleigh, and a brakeman (foreground), who does most of the pushing. This athlete must generate enough force to break the inertia of a 375-pound sled. He needs preconditioned fast-twitch muscles: larger tissue fibers capable of short, sudden exertions. That’s why bobsled scouts often recruit sprinters from track and field or wide receivers from football.

3. The big push

When the buzzer rings, the brakeman steps onto the ice, gripping two handles on the sled’s rear. He bends his knees, leans forward, and might lock his arms straight: This directs the force for the initial push horizontally, directly from the athlete’s legs—not his relatively weak arms. Exerting a combined 5 horsepower, the team can bring the sled from zero to up to 15 miles per hour in just two seconds.

4. Aerodynamic outfitters

Air drags on a fast-moving sleigh, slowing it down. And the faster it moves, the greater that backward pressure grows. So designers give a bobsled a rounded, conical nose. As it moves, this pointy prow splits the air, decreasing wind resistance. The humans also make their bodies more aerodynamic by wearing skintight compression-fabric suits that help further reduce drag.

5. Slip and slide

In ideal race conditions—a freezing, sunny day—a thin, unnoticeable film of water forms on the ice, making the surface extra slippery. Steel-alloy runners, sanded and shined, further decrease friction to allow the sled to slide. To improve traction, competitors wear shoes covered in 350 to 400 spiky steel needles, which cut into the ice with each step, allowing their feet to get a grip on the slick stuff.

6. Closing time

After that initial push, the athletes cross the starting line and continue pushing for another 65 to 100 feet. Then the pilot hops in, bringing the total weight on the brakeman up to about 575 pounds. He runs a few more steps, until his legs can’t crank any faster, and jumps in just before the sleigh reaches 25 miles per hour. If perfectly executed, the push can shave enough time to put a team on the podium.

This article was originally published in the January/February 2018 Power issue of Popular Science.