The Future Of The Fight Against Bed Bugs

If chemicals can’t save us, what will?

Popular Science contributing editor Brooke Borel suffered through bed bugs three times in New York between 2004 and 2009. Those experiences, which were part of a global bed bug resurgence, inspired her to unravel the pest’s story. This excerpt is from her new book: Infested: How the Bed Bug Infiltrated Our Bedrooms and Took Over the World.

It may be tempting to think that bed bugs could be eliminated, if only we found just the right deadly chemical formula. But uncovering new insecticides is a difficult task as well as an expensive one. According to one estimate, each active ingredient takes around a decade to develop at a cost of up to $256 million. If the chemicals can’t save us, what will? Perhaps there could be another way to go about killing off bed bugs by giving an old technique a new twist. Researchers are still trying to build a better bed bug trap, just as inventors and tinkerers did hundreds of years ago. I pored through current research to find out what they were up to. At the entomology conference I went to in Knoxville, where I saw the presentation about Usinger’s bed bugs and population genetics, another talk caught my eye. An insect biomechanics researcher at the University of California, Irvine, had run bed bug after bed bug across the underside of kidney bean leaves to understand how John Locke and people in the Balkans were able to trap bed bugs with these plants.

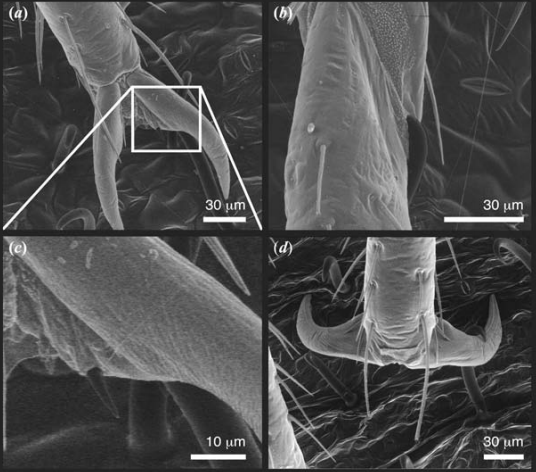

In the forties, scientists from the US Department of Agriculture showed that the small hairs on the leaves, called trichomes, might work like the hooked side of a Velcro strip by grappling the stiff hair on bed bugs’ legs. The California scientists proved this wrong by looking at bugs stuck to bean leaves under powerful scanning electron microscopes. At the conference, I was transfixed by an image that showed the sharp trichomes actually piercing a bed bug’s foot like meat hooks, tortuously immobilizing it. A synthetic version, the scientist suggested, could be manufactured and sold as a trap.

Meanwhile, I found research by scientists at Stony Brook University in New York that involved weaving webs of synthetic strands thinner than human hairs to try to ensnare the bugs. And several competing companies are experimenting with a modern plastic version of the saucers that used to be placed under bed legs, some of which come in different colors (whether bed bugs are more attracted to red or to black, I learned, is a point of debate).

There are also scientists playing with lures designed to mimic bed bug pheromones to trick the insects into thinking their brothers and sisters are sending them signals to act in a specific way. Scientists at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, for example, have collected sample after sample of bed bug poop, convinced that the feces contain the aggregating pheromones that help guide the insects home after a blood meal. As the small odorous molecules emanating from the poop waft through the air, they attach to chemical sensors on the bugs’ antennae. The bugs walk toward the increasingly intense smell until they reach their refuge, where the concentrations are greatest. The scientists are working to isolate these compounds to add to a sticky trap, which will bring the bugs in and then keep them there.

The trouble is, modern bed bug traps face the same problem as all those that came before: in order to work, bed bugs must walk through them. Even when they do, it proves the existence of the bugs in a room, but it doesn’t mean it has trapped or killed them all. This requires an inescapable mode of death. Since synthetic chemical killers are expensive and elusive, some scientists have looked for other ways to poison the insects.

Scientists from Penn State University think the answer may lie in the fungus Beauveria bassiana, which lives in soil throughout the world. B. bassiana is a biopesticide–a natural insecticide found in living things including animals, bacteria, and plants, or from minerals or oils. The fungus’s fine white dusty spores have a natural affinity for fatty surfaces. When certain insects come into contact with the spores, either through contaminated soil or other infected insects, the spores stick to the outermost layer of the waxy exoskeleton. The moisture on the insect’s body allows the spores to sprout, and they penetrate into the exoskeleton. From there, the fungus spreads, blooming in the insect’s circulatory system and clogging it.

In the Penn State tests, the scientists sprayed various surfaces, including smooth printer paper and textured jersey knit, with a milky mixture of the fungus and dropped bed bugs on top. Both Harlan bugs and a strain collected from the field died within three to six days. But to make it as a product, the fungus would have to pass EPA requirements for biopesticides, which are just as stringent as those for synthetic pesticides. Here, the agency is concerned with not only toxicity, but also hypersensitivity and infectivity. This means the agency wants proof that the fungus won’t irritate a person’s skin or pierce it and bloom inside the blood.

I also found research attempting to attack bed bugs in a place they will undoubtedly always return: blood, the same sustenance that has driven their spread for so many millennia. In 2012 I interviewed a Virginia emergency room doctor who had dosed himself and a few volunteers with ivermectin, an antiparasitic drug common to heartworm preventatives for dogs and livestock. The drug has also been used since the late eighties to treat humans for river blindness, a disease common in sub-Saharan Africa caused by different species of roundworms, and is sometimes prescribed to treat head lice, pubic lice, and scabies.

After taking the drug, the doctor and his test subjects fed live bed bugs on their arms. The ivermectin killed some of the bugs but failed to get them all, and in real life far longer treatments would be necessary than is currently proven safe. In other words: do not try this at home. (Merck, the maker of the drug that the doctor tested, politely declined to comment when I sought the company’s take on the experiment, and it is doubtful whether it will pursue clinical tests. New labels for drugs are even more expensive and time-consuming than for pesticides.)

If blood can’t be easily or safely tainted, another option is to make it useless once it hits the bed bug’s digestive tract. In 2009 scientists at the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology in Tsukuba, Japan, showed that damaging symbiotic bacteria that live in the bed bug’s gut is bad for its health. The bacteria come from the genus Wolbachia, named for one of the scientists who discovered it in the bowels of a species of mosquito in 1924. Wolbachia are among the most common beneficial bacteria that live in insects and are found in around two-thirds of the known insect species on the planet. The bacteria help pull key nutrients from food or aid in reproduction. Wolbachia are one example out of an entire microbial ecosystem that flourishes in insects, including Wigglesworthia glossinidia, which helps the tsetse fly synthesize vitamin B and is named after Sir Wigglesworth of bug hormone fame. Humans, too, have gut microbes that help produce vitamins key to our health.

The Japanese scientists suspected that Wolbachia similarly allows bed bugs to synthesize vitamin B. To test the idea, they fed rabbit blood laced with antibiotics to bed bugs in the lab, which wiped out the Wolbachia inside. Bed bugs without the symbiotic bacteria were stunted and sterile; both traits were reversed after the scientists fed the bugs blood supplemented with vitamin B. Whether the drugs could kill bed bugs in a real-life setting is unclear. Dosing a person with antibiotics could add to the growing problem of drug-resistant bacteria, adding yet another negative layer to the bed bug predicament. The bed bugs’ Wolbachia may grow resistant, too.

All of the basic research is interesting, but none could get rid of a bed bug infestation completely on its own–instead, it would need to be incorporated into existing integrated control tactics. But even so, the best traps, chemicals, or biological manipulations will never overcome an obstacle that Dini Miller pointed out to me when I visited her in Virginia.

“The hardest thing to control isn’t the bed bugs,” she said.

“What is?” I asked.

“It’s the people.”

Indeed, people hide bed bugs from landlords, skip treatments, bypass instructions on insecticide labels, fail to heed their pest controller’s guidance, and ignore sage advice on avoiding the bugs to begin with. Others accidentally set their mattress on fire with a bottle of rubbing alcohol and a match. And no technology can save us from that.