This Flexible Sensor Sticks To Your Skin And Measures Your Blood Flow

To better monitor diseases that may affect how blood flows

The blood coursing through your arteries and veins bring necessary nutrients to organs throughout the body as well as take waste away. But conditions such as diabetes, kidney disease, and certain types of inflammation can limit blood flow to various parts of the body and lead to permanent damage that is often hard to catch early on. Now a team led by researchers from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign has developed a flexible electronic sensor that can measure blood flow on top of the skin or, can possibly be implanted onto the tissues themselves, according to a study published today in Science Advances.

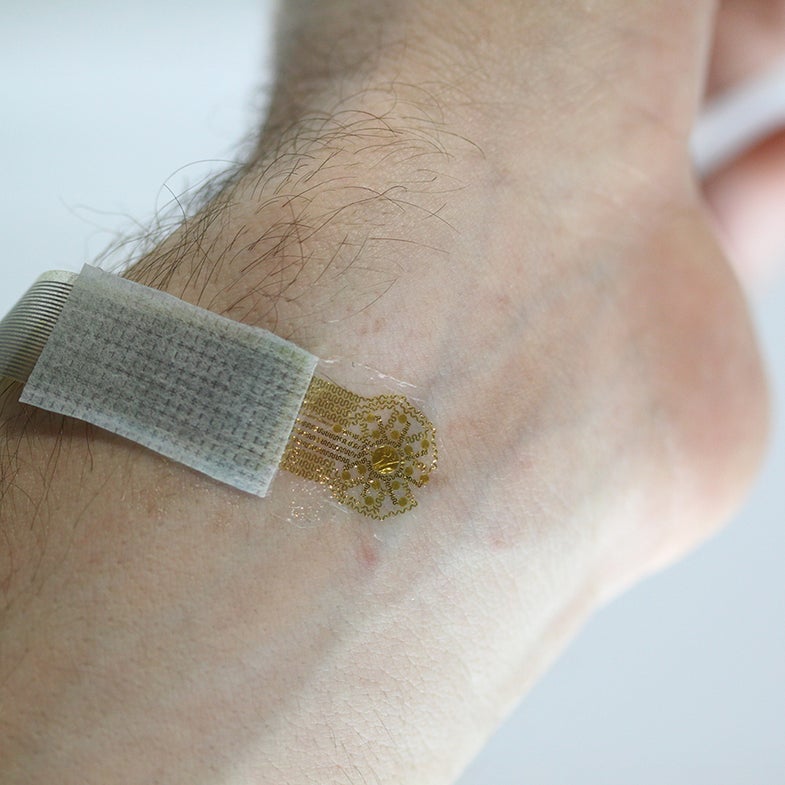

The devices are made from a thin array of metallic wires that are oriented around a central sensor and map blood flow as well as pick up on the slight temperature increase that each pulse of blood brings. They are coated in a thin layer of silicone, so they are flexible and can stick to the skin like temporary tattoos. For now, the devices need to be attached to a computer using a thin cable, but could someday connect wirelessly via Bluetooth, as do other flexible electronics from the same lab. Those devices, which have been tested in the lab, are also capable of measuring blood flow, however this new device could be the most promising one to one day make it to the clinical setting.

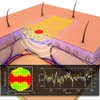

A 3D rendering of the device monitoring flow in a blood vessel below the skin. The inset graph on the left is a map of the blood flow; the graph on the right shows changes in flow over time.

Lightweight, wireless devices could be a big improvement on those currently used at healthcare facilities, which are bulky and uncomfortable, and sometimes even produce inaccurate readings. When the researchers tested their device on the surface of the skin of a few participants in the lab, they found that the readings were just as accurate and sensitive as the bulkier ones, showing where and how fast the blood was flowing. And since the devices are so easy and inexpensive to manufacture, they lend themselves well to large-scale distribution.

The researchers have not yet tested the sensors abilities when implanted below the skin as the devices would need to be totally wireless in order for that to make probable sense. But the scientists hope that future iterations of the stretchy, flexible device could be used directly on internal organs to diagnose and monitor various medical conditions that may alter blood flow.

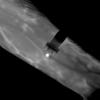

An infrared image of the device on a volunteer’s arm. The white dot is the thermal sensor.