Why it’s so hard to figure out if acupuncture actually works

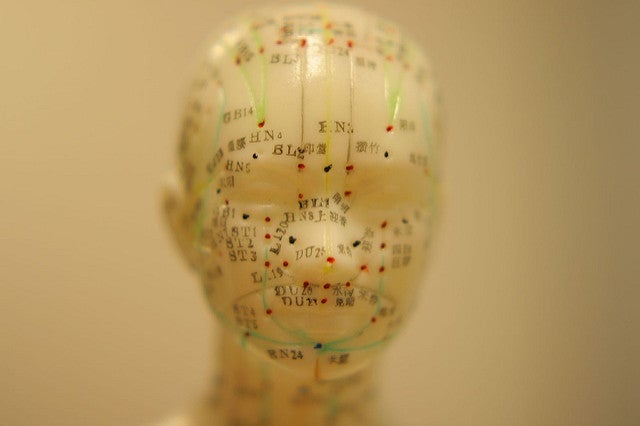

Should you stick a needle in it?

Does medicine have a bias against acupuncture?

That’s the verdict of a paper (and an accompanying commentary) published earlier this week in The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. While there’s still no medical consensus on acupuncture, and most reputable medical organizations do not support its use for arthritic knee pain, the authors’ critique lends interesting insight into the process by which medical procedures are accepted—and which are excluded.

How does alternative medicine get to be plain-old medicine?

Led by Stephen Birch of Kristiania University College in Norway, the researchers behind the new study allege that the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), which details recommended treatments for given ailments, holds acupuncture to a higher standard than it does traditional medical modalities.

If all of the treatments that NICE recommend for knee arthritis—including weight loss and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) drugs like ibuprofen—had to meet the minimum required standards that NICE sets for acupuncture, “opiates would become the first line of drug prescription,” wrote Birch et al.

Does acupuncture do anything?

To understand the article’s criticism, it helps to recognize that—despite the practice’s mystical reputation—acupuncture might actually work sometimes. Earlier this year, the American College of Physicians listed acupuncture as a minimal invasive treatment of low back pain. It should be noted, however, that most low back pain tends to go away on its own.

A more intriguing example is a March study that appeared in the journal Brain, which found that acupuncture improved the outcomes for carpal tunnel syndrome by literally remapping the brain. Researchers came to that conclusion after exposing subjects diagnosed with carpal tunnel syndrome—broken into three groups—to acupuncture treatments.

Patients in the first group received an acupuncture treatment as prescribed by traditional Chinese Medicine—that is, needles were inserted at the site of the pain. The researchers exposed the second group to something known as distal needle acupuncture, in which acupuncture needles aren’t inserted where it hurts, but rather at other sites that practitioners say are connected to the painful regions by “channels of energy.” Yes, we know this sounds like snake oil—and the study authors aren’t alleging that the so-called channels exist. But if you want to know if something—a drug, a workout regimen, or in this case an acupuncture technique—has any effect, you have to test it.

Finally, a third group received what’s known as sham acupuncture, which is essentially the sugar pill of acupuncture. In this case, sham acupuncture involved non-penetrating placebo needles designed to convince participants that they had undergone a real acupuncture treatment. Each participant received 16 treatments of their designated form of acupuncture over the course of eight weeks.

At the end of the stud, all groups equally reported that their symptoms had improved. That’s proof that acupuncture is a sham, right? Not exactly.

The researchers had specifically chosen carpal tunnel because, according to study author Vitaly Napadow, “carpal tunnel syndrome, as opposed to most chronic disorders like low back pain and fibromyalgia, is one of the few chronic pain disorders that has objective outcomes.” Napadow, who is the director of the Center for Integrative Pain Neuroimaging at the Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), says that when you’re talking about improvements in pain, the success of a treatment is basically measured by whether a patient says it’s made them hurt less.

But carpal tunnel syndrome is different. Because it occurs when the median nerve gets entrapped, researchers can actually measure the transmission rate of an impulse sent across the wrist and determine whether a given treatment improves that rate.

Napadow found that while participants in all three categories stated that they felt an improvement in pain, only participants who had received acupuncture—either at the site of the pain, or, somewhat surprisingly, via those mysterious “energy channels”—actually experienced nerve transmission improvements. And to further make the case, participants who had needles inserted right at the wrist did indeed improve even more than those who received distal needle acupuncture.

Earlier studies had shown that carpal tunnel doesn’t just causes changes in the wrist—it also causes changes in regions of the brain’s gray matter. The nerve damage in the wrist creates a sort of blurring in the brain in terms of its ability to process signals from the hand. When Napadow stuck study participants in an fMRI, he found that those pathways in the brain had improved, though he’s quick to note that even these impressive outcomes don’t equate to ‘curing’ carpal tunnel. “We improved the disorder and certainly kept it from getting worse, but we did not magically heal the patient,” he says.

But how does relate to Birch et al’s critique of the U.K.’s exclusion of acupuncture from its recommendation for knee arthritis pain?

When is a placebo not a placebo?

Recall that if you were to throw out the objective measure’s—the fMRI and nerve conductivity tests—Napadow’s study looks like a dud, because patients expressed equal levels of pain reduction whether they experienced real acupuncture or sham acupuncture.

The whole point of a placebo is that it’s inert. It doesn’t actually have an effect on the body, making it an excellent control. But physical interventions aren’t quite the same as sugar pills: even in sham acupuncture, there is some pressure or sensation being inflicted on the patient’s body. In fact, some cases of “sham” acupuncture even involve the insertion a needle, though Napadow’s study did not.

“There’s a controversy as to what sham acupuncture is,” said Napadow, “you still have a tactile sensation and a somatosensory input as a result of sham acupuncture.”

This issue isn’t limited to acupuncture. For years, studies showed that patients who had certain kinds of knee surgeries for osteoarthritis—either having their knees cleaned out with an arthroscopic procedure known as a debridement, or having the joint washed out with a saline solution known as an arthroscopic lavage—reported less pain than patients who did nothing, despite the fact that the physiological basis of the procedures were unclear—and the fact that the treatments didn’t stop the progress of the arthritis.

But still, despite the fact that there wasn’t any evidence that they actually worked, the surgical procedures were routinely done because patients reported feeling better. Ironically, that is the exact opposite of the stance that we take with acupuncture—even though it’s less invasive.

But a 2002 study in the New England Journal of Surgery studied three groups of knee osteoarthritis patients: one group underwent the arthroscopic lavage procedure, another did the saline, and a third underwent a sham surgery—doctors essentially made an incision and then stitched the person back up. As in Napadow’s study, all three groups reported an equal reduction in pain. Notes the 2002 research team, “This study provides strong evidence that arthroscopic lavage with or without débridement is not better than and appears to be equivalent to a placebo procedure in improving knee pain and self-reported function. Indeed, at some points during follow-up, objective function was significantly worse in the débridement group than in the placebo group.”

In other words, it wasn’t the procedures that helped, but the perception that someone did anything at all to help. The problem, however, as Napadow’s study illustrates, is that when we’re talking about pain—where the metric for efficacy is “do you feel better”—the perceived efficacy of a placebo intervention can equal the actual benefits of a real intervention.

And yet, NICE lists both of the procedures examined in the 2002 study as recommended therapies for knee osteoarthritis. This is in part why the new study’s authors argue that acupuncture is being held to a higher standard than other accepted interventions. Specifically, they point to how NICE uses Effect Size (ES) as problematic. In many scientific studies, something known as a P value tells us that a relationship is statistically significant—that is, that aspirin might fight heart disease, or cheese makes us happy. The Effect Size is the magnitude of the difference between the two groups—how happy does cheese make you?

NICE recommends against acupuncture because they say that the effects are too small when compared to sham acupuncture to be considered beneficial, while in the same breath acknowledging, write Birch et al, that ‘‘few if any other commonly used treatments for osteoarthritis meet these thresholds for minimal clinically important differences.’’

The researchers ask a simple question: if most of the recommended treatments fail to meet this threshold, why is acupuncture excluded while arguably more invasive procedures are included? But as patients, we should perhaps be asking a different question. Why are we being recommended procedures that don’t work?