Computer Brain Surgery Simulation Is Genuinely Gelatinous

Better tools for surgeons in training

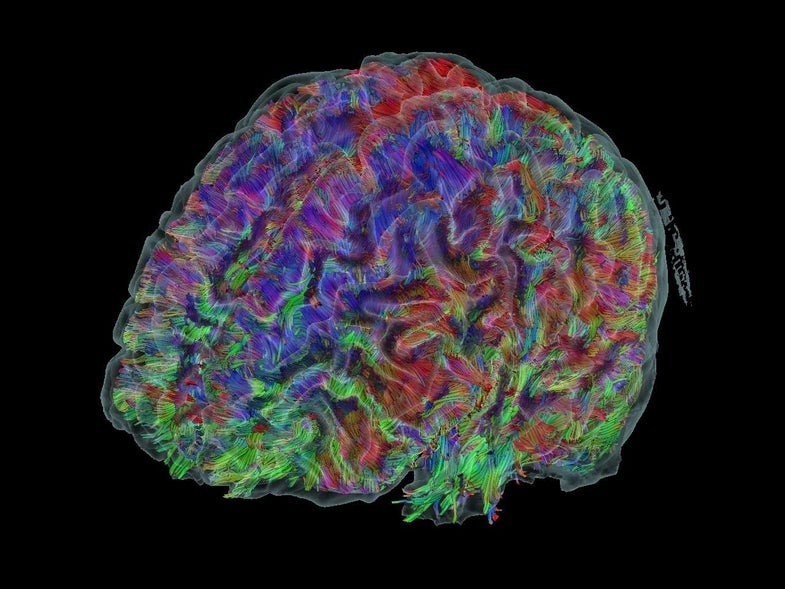

When you look at a diagram or model of the brain, everything looks to be in its place. Long-term memories are stored in the prefrontal cortex, the cerebellum takes care of balance, the parietal lobe integrates sensory information. But when neurosurgeons slice into the squishy mess that is your brain in order to do things like take out tumors, there are no such labels. That makes actually finding and removing the tumor in question (without damaging other parts of the brain in the process) a big challenge.

The Toronto-based technology company Synaptive Medical has developed a synthetic brain on which surgeons can practice before trying the real thing, according to an article published today on Motherboard. For now, all medical students practice surgery on cadavers until they advance to living humans. But the Synaptive dummy is one of the most life-like yet–it has an anatomically correct brain with the consistency of Jell-o, complete with four tumors that budding surgeons can remove. “Chemists and materials scientists on the Synaptive team worked to simulate the experience of performing neurosurgery, down to the tactile experience of living, wet brain tissue,” author Erene Stergiopoulos writes in the Motherboard piece. “It’s a level of simulation that’s almost eerie.”

The company has also come up with a better way for surgeons to see the brain during surgery. There are lots of tools designed to help surgeons visualize the brain before they perform a procedure, but during the procedure itself, awkward angles make it so that surgeons can’t see much of what they’re doing. They are often limited to surgical loupes (glasses with magnifying lenses first used in the 1800s) or a microscope arm hovering over the patient’s head.

Synaptive’s robotic microscope arm follows the surgeon’s movements, projecting an image of where she is working in the brain across two huge screens.

This has some interesting effects on surgery as well as performance. As Motherboard‘s Stergiopoulos writes:

Plus, she adds, patients are usually kept awake during brain surgery, so they would be able to see the screens, too.

This new transparency might be difficult at first, but this will likely only help surgeons in the long-term. By better stitching together the preparatory and procedural phases of surgery, surgeons could be more precise, causing less damage to the delicate organs they still can’t fully understand.