Cells Are Vulnerable When They’re Squeezed

This might indicate a new way to treat the most lethal cancers

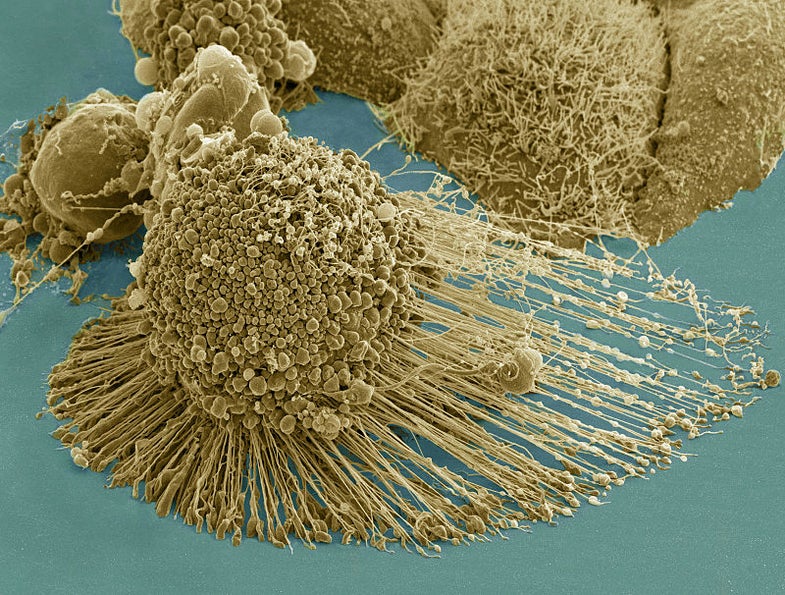

Metastatic cancer—when the disease has spread from its original site to another part of the body—causes 90 percent of cancer deaths. Once this happens, it becomes harder for drugs to target the cancerous cells. Now two teams of scientists have discovered a point at which cells are most vulnerable, which could provide a new way for cancer-fighting drugs to attack them. Both studies were published today in Science.

Whenever a cell has as nucleus, it also has a membrane around that nucleus, called the nuclear envelope, that separates it from the rest of the cell. As cells move throughout the body, they compress to move through the small spaces between other cells, and that squishing can damage the nuclear envelope or even the DNA itself.

Cells contain the machinery to quickly stitch up any damage once it happens, but that can be disrupted. In one study, conducted by a team of French researchers, special proteins fluoresced when a cell was squeezed. They investigated the protein complex that repairs the damage and found that, if they delayed the complex, the cell’s DNA and nuclear envelope was more damaged, in many cases causing the cell to die.

In the second study, researchers from Cornell University took a closer look at the nuclear envelope in cancer cells specifically. They also found that metastatic cancer cells squeezed in tight spaces within tissues and that the nuclear envelope became damaged when they did. When they impaired the protein complex’s ability to repair the nuclear envelope and the DNA itself, most of the cells died.

In both studies, the researchers concluded that a drug that could delay the repair machinery could be effective in killing the metastatic cancer cells. That could make these most virulent forms of cancer much easier to treat.