Synthetic Skin Delivers Gene Therapies Straight to Body, No Needles Necessary

The problem with needles is that nobody likes them. Aside from that, injection sites can become inflamed, and repeated injections...

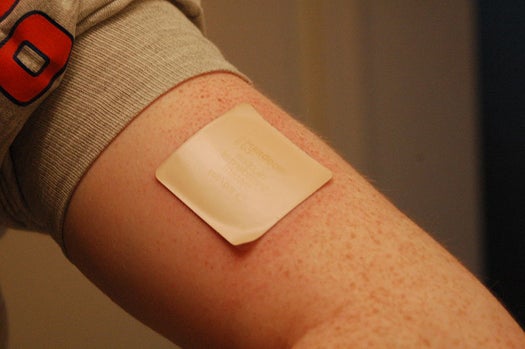

The problem with needles is that nobody likes them. Aside from that, injection sites can become inflamed, and repeated injections into the same area can damage vascular tissue (see Darren Aronofsky’s Requiem for a Dream for more graphic evidence of this). With that in mind, researchers at the National Institutes of Health have successfully created synthetic skin patches that can deliver gene therapies without the need for injections.

In this early study in mice, a skin graft was used to deliver atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), a blood-pressure-reducing agent naturally produced by cells in the heart. The researchers cultured fibroblasts and keratinocyte cells, the main two building blocks of skin, and added the genes for ANP into their genomes. They then mixed the skin cells into a gelatinous matrix, causing them to layer up just like they would in natural human skin.

The grafts were then placed on the backs of mice, where they were accepted as normal skin within a matter of weeks, at which point the new skin began dumping ANP into the mice’s bloodstreams. Radio transmitters inserted into the mice’s arteries confirmed that the grafts caused a decrease in blood pressure, keeping it down even when the mice received a high-sodium diet.

While all that is interesting to think about, it’s the method of controlling the skin patch with outside stimuli that really spells breakthrough. Say a patient’s blood pressure is on the rise; wearing such a synthetic skin patch, he or she could rub a topical cream on the patch that stimulates the ANP production, lowering blood pressure more or less on the spot. The same could be done for diabetic patients; rub a blood sugar stimulating topical on the skin patch, and a steady, heightened flow of insulin enters the bloodstream to help regulate sugar levels.

While human trials are still a few years out, the researchers envision the technology making it easier for doctors to administer genes that produce all kinds of expensive and hard-to-manufacture proteins. We’re holding out for the espresso graft that introduces a double-shot’s worth of adrenaline to the bloodstream every time we yawn.