Archive gallery: a century of vehicular DIY

The egg-shaped car, the washing machine-wagon hybrid, the home-built steam automobile, and more cars built in the garages of DIY enthusiasts.

As lovers of science and innovation, few things delight us more than tinkering around with spare parts. In our 138 years of publication, we’ve showcased scores of similar-minded inventors who could turn scrap heaps into motorcycles, robots, and four-wheelers. These people aren’t just hobbyists, they’re visionaries capable of imagining great machinery from what others had deemed broken and useless.

While people have created a great number of things from scratch, cars stand out as the prime project for professional engineers and bored tinkerers alike. We don’t blame them—who wouldn’t enjoy taking their invention for a celebratory spin upon completion? Join us as we take a look at some of the more curious vehicles assembled in garages over the past 100 years, and decide for yourself whether they’re clever or the work of a crackpot.

We begin in the spring of 1920, where a Pennsylvanian farm owner known simply as Mr. Geissinger has assembled a tractor from a stationary gasoline engine. In those days, stationary engines were used to run power tools and mechanisms like circular saws and pumps. An unlikely candidate for powering a car, sure, but its maker came up with enough scrap materials to convert it into a tractor. Granted, it doesn’t look much like a tractor at all, but we won’t spoil you—take a look below to see how Mr. Geissinger’s work turned out.

Then you have your series of go-kart-like vehicles, your bicycle-automobile hybrids, and even a couple of cage-like cars. All of the cars we cover in this gallery were made for personal use, and out of amusement, but all of them reflect how mainstream vehicles have developed over the years. A “motorized Ark” built in 1927 might resemble a modern-day funeral limousine, but during that period, it was a novel camping trailer equipped with a toilet, a stove, and a shower. Converting the chassis of a truck into a camping trailer is one thing, but to install a hotel room’s worth of amenities speaks for the dedication its creator had to his craft.

Elsewhere, you’ll find that most home-based automakers weren’t professional engineers or mechanics, but teenagers and artists pursuing a practical diversion. Not all of us carry a lot of automobile know-how, but with a little ingenuity, research, and an enviable hodgepodge of scrap items, you’ll be hosting joyrides in your washing machine-jeep hybrid in no time.

Read on to see how past hobbyists made their “midget autos,” egg-shaped cars, kitchen-equipped Fords and more.

Mr. Geissinger’s tractor: April 1920

While this homemade tractor might resemble something from a dieselpunk magazine, we can assure you that it’s a real vehicle. A Pennsylvanian farmer known only as Mr. Geissinger built his tractor out of spare parts in a scrap pile. He started with a 15 year-old, one-cylinder stationary gasoline engine, which in those days was used for running power tools, circular saws, pumps, and hay elevators. Soon enough, he assembled enough parts to give his tractor all the functions of a conventional one. It could work as quickly, had all the controls, and could turn in any direction. We reported that Geissinger successfully used it for threshing and plowing, as three plows could be attached at its rear. In total, his tractor cost $265.

The “touring Ark”: March 1924

Today, we have trailers. In the 1920s, inventor W.K. Kellogg had his “touring Ark,” a 27-foot truck equipped with everything you’d need to survive on the road: a refrigerator and ice machine, a washstand and sink, an oil stove, a fireless cooker, a toilet, cupboards, folded dining sets, a shower, a bunk, and radio set. It also held camping equipment, like a 15-foot folding motorboat. Pretty amazing for 1924, right? More so considering the abundance of luxuries in proportion to the size of his car.

Kellogg, a food manufacturer, built the Ark to indulge his lone hobby, motor touring. Not being one to rough it out in the open country or to stay in hotels, Kellogg built his car as a means of self-sufficiency. He started construction by attaching a special body and a 45-horsepower motor to a 27-foot truck chassis. Four armchairs mounted on swivels became seats, which could easily be converted into twin beds. The toilet came with running water from a pressure tank, while a small heater could make showering and travel more comfortable during winter. In total, the car weighed 11,000 pounds and could run between 30 and 35 miles per hour. Kellogg wrote this article while on the road with his wife, who accompanied him on cross-country trips taking upward of 18 months.

Washing machine go-kart: September 1932

What do you get when you cross a washing machine with a toy wagon? A car, of course—or as they called it back in the early 1930s, a “midget auto.” To build his car, Stanley McCrary, from Seattle, took the motor from an old washing machine and attached it to the wagon. He made the clutch and steering equipment by himself, and attached a little tank capable of holding a gallon of gas. There isn’t much else written about McCrary’s machine except that it could run at 12 miles an hour on level ground. We suppose the sight of a boy on his homemade auto spoke for itself.

Marcel Berthet’s Velodyne: December 1933

Unless you know your cycling history, a bike is the last thing you’d expect would be encased in Marcel Berthet’s shell-like vehicle, pictured left, above. Berthet, a French cycling champion, designed the Velodyne streamliner with Marchel Riffard, chief engineer at a renowned French airline firm. The machine was reportedly capable of moving between 40 and 60 miles an hour.

To ride the machine, the cyclist would enter a small door in the side of the shell and lower his head below the opening at the top. During race, he’d use a peephole to navigate. As strange as the vehicle looked, it was developed using principles of aerodynamics. Like the tip of a plane, the 2-foot wide front of the Velodyne was narrow enough to overcome a significant amount of wind resistance. Berthet ended up setting a new record after riding 49.992 kilometers in one hour in his Velodyne, prompting judges to ban recumbent bicycles from bike races in 1934.

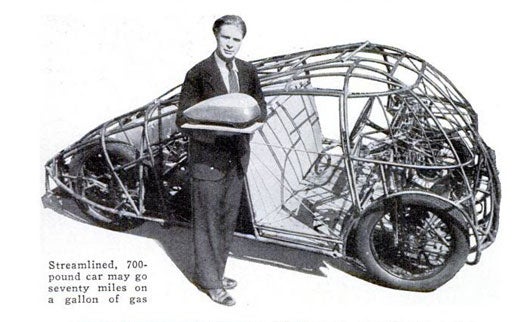

A lightweight streamlined car: October 1934

As far as home-built cars go, this model is one of the more novel designs in our archives. Dr. Calvin B. Bridges, a biologist from California, designed his car for lightness and speed. Weighing just 700 pounds, his vehicle was powered by a motorcycle engine and was expected to run 60 miles per hour. A gallon of gasoline could power it through 50 to 70 miles of travel. Like the Velodyne, Bridges’ car reduced wind resistance to a minimum, while its light frame, which was made of welded chrome-molybdenum steel tubes, would help the vehicle attain more mileage than one would expect from a car of its size.

Homemade mountain climber: November 1937

Another year, another “midget auto.” This toboggan-shaped car was built by Wallace Henderson, an engineer from Glasgow, who assembled it for fun. While it looks simple and lacks a body, Henderson’s car actually drove 3,000 feet up the Ben Lomond mountain in Scotland. His surprisingly sturdy vehicle was powered by a 2 3/4-horsepower gasoline engine located in the rear of the car behind the driver’s seat. A chain drive kept the car moving while dual tires provided additional traction. To prevent the wheels from spinning out of control, Henderson installed sheet-metal lugs on the inside pair of tires. You can’t quite see it in this photo, but a curved shield kept dirt out of Henderson’s face as he drove.

Scooter car: July 1938

At first glance, R.L. Shepherd’s homemade automobile looks like a bike, but the Los Angeles inventor touted it otherwise. His vehicle, which was again made from various old parts, could run 8 miles on one cent’s worth of oil and gasoline. A half-horsepower lawnmower and a concave chassis rendered springs unnecessary, thus easing up the vehicle’s weight. Although the car came with four wheels, only two actually drove it forward; the remaining two kept it balanced, the way training wheels do on some bicycles. While small, his car succeeded in covering 140 miles on a single gallon of gasoline.

An unbelievably fast car: December 1938

This car was built by Mylio Ozuk, a high school student from Chicago who apparently had free access to a spare parts supply. Inspired by several advanced designs for cars of the future, Ozuk placed the motor and radiator in the back of the vehicle so he could have a clear view while driving. He also applied a streamline design for speed (exterior shell not shown) and claimed his car could break 130 miles per hour. There’s no word on whether Ozuk’s claims were actually tested and proven, but we’re willing to believe that this kid enjoyed a few thrilling joyrides in his time.

Steam-powered car: June 1940

Apparently, building cars was all the rage among teenagers in the 1930s and 1940s. Two young inventors from Jamesburg, New Jersey, raided a scrap heap to create their steam-powered, three-wheeled car. Parts included two space heaters, the transmission from an old truck, and a discarded gas oven, which they used as the steam engine’s firebox. Wood served as fuel, which generated steam with a pressure of 25 pounds per square inch.

Camping car: September 1947

Just a couple of decades after W.K. Kellogg unveiled his motorized Ark, Roy Hunt, a Hollywood cameraman, showed off his own take on the live-in car concept. In addition to his own supplies, Hunt used a Ford Model-A transmission and a four-cylinder, 90-horsepower, air-cooled Franklin engine from an old war plane. He installed the engine in the rear, stuffed some kitchen and dining equipment within the front hood and tweaked the seats so they could be converted into beds.

As you can see in the pictures, his car held a remarkable number of amenities. The shotgun seat could unfold into a full-sized bed, while the kitchen set held an icebox, a sink, and a GI gasoline stove At 4 feet, 8 inches high, and 16 feet long, his car wasn’t especially spacious, so he made the doors just an inch thick to increase the vehicle’s volume.

Egg car: May 1953

This lovely little vehicle wasn’t built by an engineer, but by an artist by the name of Paul Arzens. His insistence that “the mechanism must be a means and not the end” motivated him to built a car that defied conventional car designs. He began using a frame with steering gear similar to that of a Model T Ford. Next, he added a body of aluminum tubing to the steel frame and installed an air-cooled rear engine that could provide 5 horsepower at 5,300 rpm. Next, he added a small seat slightly wider than the ones in typical French cars. To maximize visibility, he made the top third of the car all Plexiglass windows. Finally, a canvas pull-over top gave his “Little Town Car” some shade. Capable of traveling just 50 miles per hour, Arzens’ car wasn’t the fastest thing in the world, but you can’t deny that it looks nice.