Nothing makes you wish for a high-speed rail, a flying car, or a teleportation device like having to travel over Thanksgiving. Apparently, the future of chaos-free commuting is in Europe, Japan and China, where passengers enjoy the luxury of trains that glide along at 200 miles per hour. Meanwhile, those of us living in America get to choose between radioactive scanners, enhanced pat-downs, and the joy of holiday highway congestion. Injustice! Suffice to say, our maglev train envy is making the spirit of Thanksgiving a little harder to grasp this year.

Click to launch the photo gallery.

Alas, high-speed rails may not arrive on our fair shores until the year 2040. Lord knows we’ve hankered after them for a good 138 years now. Even people traveling by steam engine knew that the future of American train travel needed to break 200 miles per hour.

If there’s one thing Popular Science has taught me about retrofuturism, it’s that even the most improbable ideas never die. They crop up, go dormant for twenty years, and reappear once a new generation of visionaries grows tired of the status quo. Take, for example, the super speedy, aero transit monorail. In 1919, a French inventor proposed combining an airship, a fuselage, and a train to create a propeller-driven monorail with wings. We were interested, but skeptical that it could actually reach 150 miles per hour without using wheels. Eleven years later, a Scottish inventor built a similar train, but with an overhanging rail instead of wings. We were excited for awhile, but got distracted by magnetic levitation. In 1972, long after Japan unveiled its Shinkansen trains, we began to suspect that it’d be decades before we could implement that technology. So we began dreaming of hanging trains again, but this time, minus the propeller.

More than likely, it will be awhile before America gets its own high-speed rail. Perhaps by then, flying cars and teleportation devices will have gone commercial, thus eliminating the need for high-speed rails. One thing’s for sure though–until high-speed rails become obsolete, and as long as we have a traffic problem, our hearts won’t give up on a New York – California Maglev train.

While waiting for the turkey to finish roasting, click through our gallery to read about the Soviet Union’s amphibian rail, the Long Island/New Jersey bullet train, and more concept vehicles from the future past. Believe it or not, nine out of 10 of these railway systems were designed to beat 150 miles per hour.

Flying Train: December 1919

Francis Lauer, an inventor from Paris, dreamed of combining an airplane and a monorail to achieve what he called “guided flight.” Although we dismissed the project’s aeronautic capabilities and questioned its cost, we admitted that the project could be a good scientific experiment if Lauer found the proper funding. His flying train would consist of one egg-shaped car with four stories: one for the luggage, one for about 30 passengers, one for the engine and one for the operator. To steer the egg, the operator would use a lever to turn the wings. We pointed out a number of practical issues with the machinery: for one thing, the propeller would have to be huge in order to move the heavy, four-story car forward. Secondly, the foundations would be expensive to build. Finally, the use of wings instead of wheels meant that the car would move very slowly. Despite its potential as a study in aviation, we concluded that Lauer’s monorail flier would be better off as a pocket-sized toy. Read the full story in “He Dreams of Flying on a Rail”

NYC’s Suspended Railways: March 1923

By the early 1920’s, New York City officials new that they needed to fix their automobile traffic problem. Gustav Lindenthal, who designed the city’s Hell Gate Bridge in 1917, proposed building a vast web of steel-cable suspension bridges all over the city. Long, cylindrical monorail trains would zip through hanging airways while transporting commuters from the suburbs to skyscrapers. Passengers would enter the airway using elevators installed on buildings. R.C. Lafferty, a New York engineer, had a similar idea, except that his bridges wold include a motor speedway below the railway. Like Lindenthal, Lafferty favored monorails, arguing that they would suffer less damage over time than traditional train cars. At the time of this article’s publication, the New York Transit Commission considered Lafferty’s idea a viable solution to the growing congestion of New York City streets. Read the full story in “Proposes Suspended Railways to Bridge Cities!”

The Soviet Union’s Amphibian Monorail: July 1934

Turkestan, which encompasses much of modern-day Central Asia, is rich in natural gas and oil resources. The reserve of mineral wealth, however, required a long journey through the deserts and down the Amu Darya river. To ease travel, the Soviet government planned three amphibian monorail lines capable of moving at 180 miles per hour. Twin air-propelled cars would carry 40 passengers. Upon reaching the river, the cars would be taken off the rails and used as a boat. In total, their monorail line would measure 332 miles in length, and each car would come equipped with a diesel-electric motor, a fuel tank, and a water ballast. Since it was the year 1934, however, the Soviet Union got caught up in more pressing matters, leaving the project all but forgotten. Read the full story in “Twin Amphibian Cars for Monorail”

How the Scottish Will Travel: October 1930

Is it just us, or does this airplane fuselage train look like an awesome way to travel? To facilitate a faster commute between cities and suburbs, Scottish inventor George Bennie developed an overhead monorail driven by electric motors and air propellers on both ends. If all went as planned, the trains would zoom along at 150 miles per hour, which is an impressive speed for interurban transit even today. Visitors to the Transport Congress in Glasgow were able to see a portion of it in action near the city of Milngavie, where the first cars had been built. Although the tracks were too short to for the train to reach its intended speed, officials both in and outside of Scotland were eager to implement the technology in their cities. New York City briefly considered a similar structure for an outer borough, although their model would run at only 45 miles per hour (sounds about right, eh New Yorkers?) Read the full story in “Monorail Aims at High Speed”

New Train For Old Tracks: April 1935

Apparently, monorails were all the rage prior to the post-war era, as we uncovered an inventor’s proposal for installing monorail cars on exisiting railroad tracks in Cleveland Heights, Ohio. Unlike other monorail cars, which used overhead railways to stay in place, these cars would use the air propeller to stay upright. It sounds a little far-fetched, but evidently, the propeller would be positioned in a way that allows it to tilt on either side of the car, much in the way that a bicyclist leans inside of a curve when turning. An air rudder would provide additional balancing support, while the car’s built-in pendulum would “alert” both mechanisms when the car went off-balance. Read the full story in “Monorail Car Rides Ordinary Tracks”

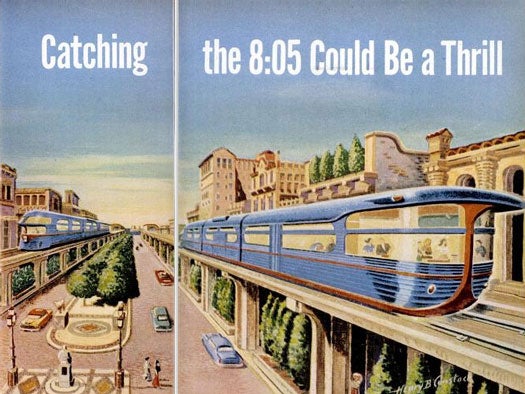

High-Speed Long Island Railroad: March 1954

When you live in New York, catching the train during your morning commute is a pain in the ass. John A. Hastings, a former New York state senator, recognized the pain of running like a fool toward a train that would inevitably zoom away just as you arrived on the platform. To ease Manhattan’s rush hour, he recommended installing trains capable of running 150 miles per hour on the Long Island and New Jersey railroads. Although 150 mph sounds pretty darn ambitious for our beloved LIRR, Hastings insisted it could be done with his new cartruck and rubber-cushioned roadbed technology. Rubber insets on prestressed concrete roadways would reduce side sway, allowing his lightweight electric trains to zip along at 2 and a half miles per minute. The project would cost the city $900 million. Not surprisingly, transportation authorities were skeptical of Hastings’ expensive idea, but the city of Havana, pictured left, expressed interest in his high-speed transit methods. Read the full story in “Catching the 8:05 Could Be a Thrill!”

Two-Headed Trains: March 1956

Talk about a convenience contemporary society takes for granted. Before diesel and electric machinery came along, commuters regularly rode trains resembling the Hogwarts Express, but with infinitely less magic. That is, the trains were slow, and they were susceptible to precipitation. With a locomotive in the front and back, trains developed for the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad would only be able to run in one direction, but they would run extra fast–one locomotive would push, and the other would pull, allowing the trains to cut through the northeast corridor with unheard-of precision. We estimated that the new “Speed Merchants” would reduce travel time between New York and Boston from four hours to three. Plus, unlike its predecessors on the New Haven Railroad, these trains would be allowed into Grand Central Station’s electric-only tunnels, where the old diesel-sputtering trains were strictly prohibited. Read the full story in “You’ll Soon Ride Two-Headed Trains”

Bullet Trains for Britain: November 1961

By the 1950’s, we knew we were close to a high-speed rail revolution, but the question of who would master the technology first remained until 1964, when Japan unveiled its Shinkansen trains. Three years prior to the HSR breakthrough, Great Britain announced plans to build a bullet train that could break 200 miles per hour. Dr. Eric Laithwaite, an electrical engineer based in Manchester University, gave us a peek into what he believed was the answer: trains with no moving parts and no drive wheels–a linear motor would convert electricity into power without using gears and wheels. To achieve high speed, Laithwaite’s train would move electromagnetically along aluminum strips along the track. He also considered eliminating wheels entirely, relying instead on jets of compressed air to elevate the train slightly, thus allowing it to zoom along without wheel-ground friction. Despite the British Transport Commission’s initial excitement, Great Britain did not open regular high speed rail service until the mid-1970’s–and even then, the trains ran at just 125 miles per hour. Read the full story in “Straight-Line Electric Motor Promises 200 -m.p.h. Train”

Driverless Train: March 1963

Nowadays, people love complaining about the hike in public transportation fares, and for good reason: for instance, paying over a hundred dollars for a monthly subway pass in New York seems ridiculous to commuters who paid 70-some dollars for the same pass just five years ago. While current transportation authorities have yet to find a cost-effective solution that will satisfy the public, back in the early 1960’s, Westinghouse announced plans to cut labor costs in Pittsburgh by incorporating driverless trains in the city’s rapid-transit system. During off-peak powers, cars holding 20 individually-seated passengers would run one at a time, while rush hours would employ trains made up of 10 cars. Conductors would run trains remotely from a central control system, which would keep them gliding along at 50 miles per hour in either direction. Read the full story in “Driverless Train for Low-Cost Rapid Transit”

Aerial Transit System: May 1972

Now doesn’t this image look familiar. In his 1972 State of the Union Address, President Nixon pressed transportation authorities to work on de-congesting traffic from major metropolitan areas. Although the improved number of mass transit vehicles helped people get around without cars, it seemed like traffic only continued getting worse. To investigate why that was the case, we talked to the Department of Transportation, who divulged several potential solutions to the traffic problem. Most of these ideas involved fancy new trains–for instance, the Aerial Transit System concept pictured left would rush above traffic jams at 120 miles per hour. Although we were intrigued by aerial trains and magnetic levitation vehicles, especially given the success of Shinkansen, we knew we were fighting an uphill battle to implement similar technology in America. Bleakly enough, we conceded that the expenses, time consumption, and even the stubbornness of citizens who distrusted technology would slow down the glamorous future we envisioned just two decades earlier. Read the full story in “The Transportation Muddle”