How Long Before Our Cars Can Talk To Each Other?

The National Transportation Safety Board is pushing for an accelerated rollout of vehicle-to-vehicle communication systems.

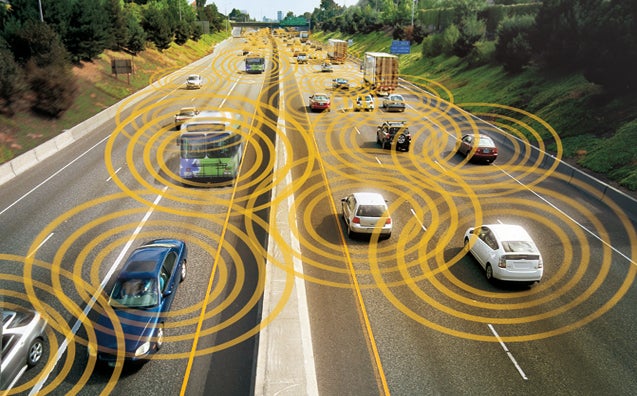

We’ve spilled a lot of virtual ink over vehicle-to-vehicle and vehicle-to-grid communications. Both are promising technologies that could substantially reduce the number of traffic accidents and fatalities by allowing cars, traffic lights, and other elements of the driving environment to “talk” to one another, spotting trouble long before it happens.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration has been testing such systems in six U.S. cities. Now, according to NBC News, the National Transportation Safety Board is calling for an accelerated rollout of the technology on new cars.

The NTSB’s recommendations come in the wake of two fatal school bus crashes—one in New Jersey, the other in Florida. In both cases, large trucks collided with buses at intersections, causing the deaths of young students.

From a technological perspective, the deployment of V2V and V2G systems makes a great deal of sense. Compared to other devices scheduled to appear on cars in the near future—devices like data recorders and backup cameras—V2V and V2G would likely result in exponentially safer roads and up to 81 percent fewer collisions.

What’s more, the basic technology behind V2V and V2G systems already exists, and it could theoretically be scaled up fairly quickly. There are, however, at least three hurdles to overcome: bandwidth, money, and the law:

By “bandwidth”, we don’t mean the speed of the networks carrying and analyzing all this new data (though that could be a major concern in some areas). Instead, we mean the ability of corporations and governments to develop and install the devices, and subsequently, assess the findings.

This would likely be easier for car companies, who would simply need to place electronic beacons on vehicles. It could be much harder for cash-strapped municipalities to install cameras at every intersection. And of course, for every car or signal light without those devices, the systems become slightly less effective.

Then there’s the question of money. The new technology would likely keep motorists safer on the roads, but how much would new-car buyers be willing to shell out for it? How would cities pay for all the devices used to monitor traffic?

Legal hurdles are even more complicated. As with autonomous cars (in which V2V and V2G technology will play a major role), there’s the question of fault to consider. If accidents happen after the systems debut—as they surely will—who’s at fault? The drivers? The automaker? The device manufacturer? The entity that monitors the network? And who’s responsible for maintaining that network anyway?

There are other issues to consider, too—not least of which is the issue of privacy. After all, in order for these networks to function properly, they’ll need to track every car’s location, and if they’re tracking every car’s location…well, you see where that could lead.

More From The Car Connection:

2014 BMW i3: High-Tech Electric City Luxury

The Most Beautiful Cars Of 2013

Acura NSX Prototype: See & Hear It on Track

And let’s not forget about hacking: when we move from closed-car systems to true car networks, our vehicles become far more vulnerable to baddies.

Don’t get us wrong: we’re big fans of V2V and V2G. Besides, these tech genies are already out of the bottle, and there’s no shoving them back in. It’s not a question of if these networks will arrive, but when.

Before that happens, though, the NTSB, NHTSA, and many other organizations need to lay out new ground rules, because this is a whole new ball game.

This article, written by Richard Read, was originally published on The Car Connection, a publishing partner of Popular Science. Follow The Car Connection on Facebook, Twitter, and Google+.