Bob Lutz never minces dreams. The 70-year-old ex-BMW, ex-Chrysler, ex-Ford executive and ex-U.S. Marine Corps aviator joined General Motors last September with a no-nonsense, ambitious agenda. His immediate task as the automaker’s vice chairman and product czar: to snap the world’s largest vehicle manufacturer out of its longstanding, self-inflicted catatonia.

For Lutz, it was dj vu all over again. As Chrysler’s head of sales, marketing, and product development from 1986 to 1998, he helped transform the company’s outdated and boring vehicles into a bristling lineup that included the Dodge Viper sports car, Plymouth Prowler hot rod, Jeep Grand Cherokee, and Ram pickups.

But the challenge at GM was more overwhelming. By the time Lutz arrived, the company’s U.S. market share had slipped to well below 30 percent, from nearly 50 percent two decades earlier. With too many divisions, more than 100 product lines, and frequent turf battles, GM was a bloated bureaucracy. Evidence of this was everywhere. For one thing, there was the new Pontiac Aztek, a combination sport sedan, SUV, and minivan whose ludicrous design caused customers to avert their eyes in disgust. And though Cadillac had attempted to come up with new, updated styles, most of the younger buyers the division was targeting showed no interest. Meanwhile, the once indomitable Oldsmobile was being phased out, and Chevrolet, which used to brag it was the perfect car in which to “see the U.S.A.,” had devolved into a truck maker.

GM needed shock therapy. Lutz decided what was required was a dramatic display of creativity. He wanted to show the world that GM was back online and that he was fully in charge-that the planet’s gutsiest car enthusiast was calling product shots from the company’s Renaissance Center towers.

Half a mile west of Lutz’s office stood the perfect stage for such a spectacle. Detroit’s Cobo Exhibition Center hosts the annual North American International Auto Show every January. Lutz wanted to take that opportunity to unveil a stunning new GM dream machine. But the timing was against him: He had just four months at his disposal, and planning, designing, and building a credible concept car-one that runs-ordinarily takes at least twice that long, even with a multimillion-dollar budget. The car czar faced a choice: Wait a year to make his statement or forge ahead with a push car.

Waiting was out of the question. Instead of squandering time on consumer clinics or tapping the company’s already murky crystal ball, he shot from the hip. He launched a design competition within the company, challenging his employees to make an affordable two-seat roadster that would squeeze the best out of GM’s neglected creative juices. “Keep the car simple, pure, and beautiful,” Lutz decreed, “and it will be easy to love.” He gave his designers a week to submit their ideas.

Along with a hundred or more of his colleagues, exterior designer Franz von Holzhausen put pen to paper. Though he had worked in GM’s North Hollywood, California, studio for less than two years, the 33-year-old auto artist was no stranger to crash programs. At Volkswagen, he had helped shape the Concept One (precursor to the New Beetle), the Audi TT, and the Microbus show piece. “Sports cars from the ’50s and ’60s are my favorites,” says von Holzhausen. “The competition began shortly after I attended the Monterey Historic Races in northern California, so superb Jaguar, Alfa-Romeo, and Cheetah designs were fresh in my mind.”

For the most part the designers, von Holzhausen included, submitted sketches of rakish roadsters adorned with chariot-sized wheels and rubber-band tires. But when Lutz sat down to review the hundreds of submissions, it was a flaming orange coupe that caught his attention. “On a whim, I tossed that sketch in at the last minute,” von Holzhausen says. “The following week, when my boss told me my theme had won, it was pure elation followed by panic (because of the) daunting deadline.”

The race was on. While GM’s West Coast team studied two rival roadsters-Honda’s S2000 and Mazda’s Miata-to help them lock in basic wheelbase and track dimensions, a surreptitious plan was being hatched in Detroit. GM’s executive director of design engineering, Mark Reuss, conspired with project manager Mike Lyons to push Lutz’s dream even further. Instead of building the fiberglass push car their boss had ordered, the two decided to build a real steel-bodied running prototype. It was a risk. Knowing their jobs could be on the line if the scheme backfired, Reuss and Lyons decided to keep Lutz in the dark as long as possible.

To compress the schedule, GM engineers decided to use as many off-the-shelf mechanical parts-from existing GM cars-as possible. Lyons recruited a small army of Detroit-area subcontractors to handle the myriad engineering and construction tasks involved in creating the body, chassis, powertrain, and various other odds and ends. Wheel to Wheel, a company with extensive prototype and concept-car experience, would build the engine and transmission. Roush Industries would supply the chassis, brakes, and suspension. InSite Industries was hired to provide stamping dies and steel body panels. Special Projects was assigned the critical task of gathering components from the other contractors and assembling them.

Naming the car was another challenge. Pontiac, which had just painfully announced that 2002 would be the last year of its 1960s-era muscle car, the Firebird, desperately needed a lift. So Lutz put the new concept car under Pontiac’s imprint. None of the designers or engineers was particularly cheered when Pontiac proposed the name Solstice, but it stuck after more evocative suggestions failed legal department scrutiny.

Meanwhile, on the West Coast, von Holzhausen’s design crew bid goodbye to the beach and began clocking 13- to 16-hour days, seven days a week. To save a week or two, they skipped the usual step of building one-third-scale models; they advanced directly from sketchpad to full-sized clay models. Von Holzhausen’s group pushed and scraped clay by hand for five weeks to create a model of the Solstice’s exterior, while a team led by designer Vicki Vlachkis sculpted the interior. When hand-shaping of the clay models progressed too slowly, a Tarus computer-controlled milling machine was used to revise character lines or surface sweeps. As portions were finished, technician Nick Mynott lifted cross-sectional data from the clay models with a three-axis coordinate measuring machine and logged it into a Silicon Graphics Octane2 workstation.

This so-called math data-numerical descriptions of planes, surfaces, and solid volumes that would become the car’s hood, windshield, and doors-was then sent via phone lines to engineers at the GM Technical Center in Warren, Michigan. The engineers compared the data against their own math files, which represented the size and shape of every major Solstice component, to make sure the mechanical parts they were working on would fit within the car’s racy lines.

Speed was of the essence, and digital communication was the buzz that kept the creative process on the fast track. Once the clay models were complete, they were scanned by a laser beam-a 4-hour process that yielded a detailed image of the entire car. That data was instantly broadcast to Warren.

On Oct. 26-54 days into the project-the West Coast team loaded the Solstice clay models and their computer-design workstations into a truck destined for Warren. Shipping both hardware and massaged clay seems out of sync with the digital age but, as von Holzhausen explains, designers don’t trust two-dimensional representations of their work. Besides, to offer Lutz and the other executives a choice between two kinds of surface treatments, headlamps, tail lamps, and grille designs, the clay model of the exterior was split down the middle, with different styling on the right and left.

Von Holzhausen caught up on lost sleep while the Solstice spent the next three days en route. Upon the car’s arrival in Warren, Lutz and GM design vice president Wayne Cherry chose the designs they preferred and asked for minor fine-tuning of the overall look. That put the burden back on the West Coast group to work feverishly to make the requested alterations in both the clay and its corresponding math model. “Our backs were against the wall,” says von Holzhausen. “We faced the deadline for forwarding finished math data to the body panel vendor, so we used every tool in our repertoire to save time, including the milling machine in place of hand sculpting.”

InSite began stamping-die construction for the body panels on Nov. 13. Tape-controlled milling machines (similar to the Tarus mills used to carve clay) directed by GM-supplied math data cut into solid chunks of material-either machinable urethane or a metal alloy called kirksite-to create the dies that would be used to press flat steel sheets into compound-curved body panels. A matched pair of male and female dies was created for the more complex panels. A proprietary technology in which a flexible bladder served as a substitute for the male die was used for the smaller, simpler panels. Metal pressing began on Nov. 24 and, with no Thanksgiving Day break, the 21st and final panel was stamped on Dec. 3. After laser trimming, the panels were positioned on a holding fixture for presentation to engineering director Reuss and project leader Lyons. “I had spotlights all over our panels,” InSite manager Jerry Leitch recalls. “When the wraps were pulled off, Reuss’ and Lyons’ faces sparkled with nearly as much delight as when Bob Lutz drove the finished car onto the stage in Detroit.”

A frenzy of activity was under way at Special Projects long before the body panels arrived. GM designers had set up shop with their computer workstations and their clay models. The instrument panel and center console were molded out of fiberglass, which was also used to create a just-in-case set of exterior panels. Structural components fabricated at Roush Industries arrived and were welded together. Wheel to Wheel delivered the engine-a 2.2-liter GM Ecotec four-cylinder reconfigured for longitudinal mounting and supercharged to boost output to 240 horsepower. Donor parts drawn from a Chevy Cavalier (front suspension), Subaru Impreza (steering gear), Buick Rendezvous (rear suspension), Chevrolet Trailblazer (differential), Chevrolet Corvette (six-speed transmission), and Cadillac CTS (brakes) were modified where necessary, then bolted in place. “The amazing thing is that all those parts fit just as the math data predicted they would,” says Special Projects owner Ken Yanez. “Everything bolted in as intended.”

The car was 60 percent done when Lutz realized what was happening. “When he saw real brakes and an engine going in, he said, ‘Oh my gosh, you guys are making this thing a runner, aren’t you!'” says Reuss. “Sitting on a milk crate with a wheel in his hands and an empty instrument cluster, he turned to me like a kid with a smile on his face and said, ‘I can hardly wait.'”

Lutz’s reaction lifted the team’s morale and made the long hours and lost weekends worthwhile. While dozens of craftspeople welded, bolted, and fabricated, von Holzhausen and Vlachkis used computer-aided manufacturing tools to hone the car’s most intricate details, such as instrument bezels, radio knobs, headlamp lenses, and grille panels. Stereo lithography, laser sintering for bonding metal parts, and laminated object assembly equipment helped the pair convert screen depictions of parts into three-dimensional solid objects in a fraction of the time that it would have taken using traditional methods.

The final leg was an intense three-day thrash, with 100 or more participants working, napping, or just lending moral support. “The night before the Jan. 6 show, we all took a break at 2 a.m. to enjoy some of my wife’s homemade bread,” says Lyons. “Everyone had that look of determination on their faces that this project was not going to fail.” By 6 a.m., the car was complete.

A mere 6 hours later, a beaming Bob Lutz drove the sleek silver Solstice into the North American International Auto Show to a rave response. AutoWeek gave the two-seater its Best in Show rating. For the Solstice’s creators, there was another level of satisfaction: They had begun a revolution in the time it takes to make a working prototype. Designers at every automaker in Detroit are now struggling to speed up the pace from concept to finished car-though it’s unlikely that others will follow a four-month schedule that cost GM up to three times more than normal. As for GM, its Pontiac division is considering including a $20,000 version of the Solstice in its 2005 lineup.

Of all the automakers, nobody would have guessed that GM would be the one to set such a radically new benchmark. But then again, GM never had Bob Lutz at the helm before.

“I was excited from the beginning,” says von Holzhausen, “because it was Lutz’s first GM project. He said it best: ‘While you never forget the cars you work on throughout your career, you always remember the first as the sweetest.'”

HOW DID THEY SAVE SO MUCH TIME?

On Aug. 2, 2001, Robert A. Lutz was appointed GM’s vice chairman of product development. Before he even got there, he hatched a plan to produce a visionary sports car for the upcoming Detroit auto show. It usually takes at least eight months to build a working showpiece; Lutz had just four. Here’s a brief history of the Solstice, with comparable milestones for a more typical driveable concept car.

Lock and Roll

An attack copter shows off new antimissile ware When Major Wandent Brawdsen of the Royal Netherlands Air Force rolled his Apache Longbow helicopter and fired a string of flares during last year’s Royal International Air Tattoo in Fairford England, it wasn´t just an air-show stunt. He was demonstrating the first and only Apache infrared missile-defense system. The new technology is sorely needed: When an attack chopper drops down to take out a target, it becomes an easy mark for shoulder-fired missiles such as those that were thought to have been the cause of two U.S. Apache pilot´s deaths in Iraq earlier this year. The ultraviolet sensors mounted beneath the aircrafts’s wingtips detect and track missile exhaust and then fire off infrared flares to confuse the projectiles´ guidance systems.

Wave Rider

The biodiesel-fueled boat has a triple-hull design that allows it to pierce 50-foot waves. A prototype is pictured here.

Low Rider

One day. One bullet-shaped bike. One crazy world record In late July, Canadian triathlete Greg Kolodziejzyk pedaled his recumbent bicycle 650 miles around a California track to break the human-powered 24-hour distance record. Equipped with food, water and waste bags, the 70-pound carbon-fiber machine is capable of hitting 60 mph on a flat straightaway. â€Once you get over 12 or 15 mph, 90 percent of your pedaling effort goes to pushing air,†Kolodziejzyk says. â€The key to going fast under human power is to minimize the hole you punch†in the atmosphere. To build a bike that did just that, Kolodziejzyk teamed up with fairing designer Ben Eadie, who used flow-dynamics software to test dozens of designs in a virtual wind tunnel. See more details at adventuresofgreg.com

Brain Monitor

Is this the future of the home theater? No, it´s not a prop. This six-pound helmet monitor is a real prototype, built to demonstrate next-generation television-watching technology. Modeled here by one of its developers (the regular TV is shown only for comparison), the device was built by Toshiba and unveiled in September at an academic conference in Osaka, Japan. Equipped with a built-in projector and a dome screen, the monitor plugs directly into a DVD player or computer and provides an immersive experience that surrounds the wearer with the action of the program-think of it as a portable IMAX theater. Although the invention was popular among testers, who reported that it rests easily on the shoulders and is comfortable enough for a two-hour movie, Toshiba has no solid plans for commercialization.

Ice Ice…Maybe

Glacier National Park could be due for a name change Photographs like these might soon be all that’s left of Grinnell Glacier, seen at left in 1938 and at right in 2005, globally the hottest year on record. The 7,000-year-old ice monolith, located in Montana’s Glacier National Park, has shrunk by 70 percent in the past century or so. “Virtually all the glaciers of the world are retreating,” says ecologist Daniel Fagre of the Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center, stationed in the park. “It’s clear evidence of global climate change. They don´t retreat for any other reason.” If temperatures continue to climb at current rates, the last of the park´s glaciers will vanish by 2030. Visitors, Fagre says, are conscious of the deadline: “We hear more often that people want to come see the glaciers before they disappear.” _Related:_

Behind the Images: PopSci´s staff photographer talks about some his favorite shots

Mini Machines Photo Gallery

Low Rider

Kolodziejzyk circled the Eureka, California, track 1,800 times.

Race Day

Kolodziejzyk with his wife, Helen, and designer Ben Eadie before the attempt.

Blue Haven

Like a watery elevator shaft, this blue hole plunges 200 feet straight down from the surface of Abaco Island, in the Bahamas. Found below the seafloor and on tropical islands, blue holes formed after the last ice age, when meltwater flooded vertical caves. A research team led by Texas A&M; marine biologist Tom Illife visited Abaco earlier this year. Its mission: to collect specimens in the unusual waters, where oxygen content is low and salinity varies dramatically from the surface to the depths. Scientists suspect that thousands of ancient species have been preserved in blue holes, many of them living fossils of creatures once thought extinct. Illife´s team found what could be several new species of crustaceans.

Life in a Bubble

A Milky Way supernova is providing clues to the origins of planets-and people Cassiopeia A, the remnants of the most recent star to explode in our Milky Way galaxy, is only 10,000 light-years away, close enough for astronomers to get a detailed look at it through the Hubble Space Telescope. By comparing this composite image of Cas A with one taken nine months earlier, scientists have discovered that the glowing cloud of debris left behind by the supernova is not expanding uniformly, as was once assumed. Instead two opposing jets of material are moving at 32 million mph, about 20 million mph faster than the rest of the debris [in this image, one stream extends from the upper left side of Cas A]. Another surprise: This view, which highlights different elements by color (for example, oxygen is shown as green), shows that materials of similar chemical composition remained clumped after the explosion. Supernovae are a major source of all elements heavier than hydrogen and helium and the primary source of heavy elements like iron. These scattered elements eventually coalesce into new stars and planets. They are also what we´re made of.

666 Legs to Stand On

After eluding biologists for 80 years, Earth´s leggiest millipede resurfaces Don´t be fooled by the â€milliâ€-nature hasn´t cooperated in turning up a 1,000-legged grub. The species that comes closest is Illacme plenipes (Latin for â€plentiful feetâ€), and until last fall, when East Carolina University Ph.D. student Paul Marek spotted it in California´s San Benito County, the odd crawler hadn´t been seen since 1926. The rediscovery offers a chance to study the critter with modern tools. This microscope image, for instance, magnifies the millipede 1,270 times. Turns out the gonopods (blue and yellow) are modified leg structures rubbed together to deliver sperm; their hooklike design allows the grub to grasp its mate. Will we ever see a true 1,000-legged millipede? Maybe. Since Illacme plenipes continues to grow new segments throughout its lifetime, it´s possible one could hit the magic mille if it lived long enough.

FLIPPER SHOCK

After years of waiting, a peek at a walrus feast Before Swede Gran Ehlm began photographing walruses a decade ago, it was unclear how they ate. No one had ever witnessed the dangerous 3,000-pound mammals in the deep water where they spend most of their day, unearthing clams from under the ocean floor. It took Ehlm years to learn that the best time to approach the herding animals is when they are alone, and that they are calmest when feeding. But his patience paid off. Last year, he became the first person to document the fact that the walrus employs its flippers to dig up its meal. “That was new to science,âa¬ he says. Ehlm spent hours in the frigid waters off the coast of Greenland to capture this image-and then almost erased it. âa¬I didn´t know how long the session would take, and I didn´t want âa¬no memory´ to flash,âa¬ he says. âa¬So I was just deleting, deleting, deleting. Then I noticed the head sticking out of the sediment. It was very close.âa¬

Fill ‘er Up

A spate of enormous hornet nests may be a sign of a warming Earth In early May, Harry Coker of Tallassee, Alabama, peered into his parked 1955 Chevy and saw a yellow-jacket nest â€the size of a spare tire†on the floor of the backseat. Six weeks later, Coker went back-and found the nest had grown to fill the entire car. Yellow jackets normally construct hives no bigger than a basketball, populated by one queen and at most 3,000 workers. But this year, giant nests are cropping up all over Georgia and Alabama. Auburn University entomologist Charles Ray has documented at least 60, some containing 100,000 workers and hundreds of queens. Ray finds the sudden phenomenon puzzling but speculates that warmer lows in winter-January was six degrees above average this year in Alabama-allowed workers usually killed off by cold to survive into spring, altering the behavior of some colonies.

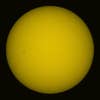

HOT SHOT

Against a perfect backdrop, the space shuttle undocks from the ISS No, it´s not dust on the lens. The specks on this image of the sun are in fact the International Space Station and the space shuttle Atlantis. Less than an hour after the shuttle detached to return to Earth in September, astrophotographer Thierry Legault captured this image from a cow pasture in Normandy, France. It was his consolation prize: He´d hoped to shoot the docking of Atlantis, but climate got in the way. âa’¬The weather was awful all week, and I had only been able to take my chance during a small moment of clear sky,âa’¬ explains Legault, who used special software to predict the alignment of the station and the sun and shot the photo at an extremely fast 1/8000s shutter speed. His camera was mounted on a telescope with a solar filter-which produces black-and-white images that Legault later colorized-and a motorized base to track the sun. When he took the picture, the shuttle was about 350 miles away. The sun? Some 93 million miles.

In Saturn’s Shadow

A bit of shade helps Cassini see new rings-and home While traveling through Saturn´s shadow last September, the spacecraft Cassini was able to shoot a remarkable series of photographs from a perspective that would normally fry its optics. The images, taken over the course of nine hours and combined here into a panoramic composite, capture for the first time the giant planet and its dazzling array of rings backlit by direct sunlight. The perspective has revealed two never-before-seen rings, faint bands of dust apparently thrown up by meteorites hitting moons. â€The tiny particles are highlighted,†says Carolyn Porco, leader of the Cassini mission´s imaging team. â€It´s the same effect that makes the dust on your windshield very obvious when you´re driving into the sun.†But the image´s most striking feature, Porco says, is that bluish speck on the left: â€What an amazing sight to see Earth-so small, so fragile-looking-nestled in Saturn´s rings.â€

Uneasy Breathing

In a disastrous year, the mining industry looks more closely at its survival gear This picture was taken outside Pennsylvania´s Twin Rocks coal mine last spring. But it could easily have been taken 25 years ago, mining technology has evolved so little since then. Miner Joe Tenerowicz is demonstrating a self-rescuer, a chemical-based oxygen-production system that provides an hour of backup air. The device, which has been the standard emergency breather for a quarter century, was the only technology available to coal workers in West Virginia´s Sago Mine tragedy, which left 13 dead last January. This year has proved particularly fatal for U.S. miners; to date, 37 have died in 21 incidents, a 30 percent higher rate than in recent years. For the industry, it´s been a wake-up call. Under the federal Miner Act, which went into effect in June, better devices-including replacement cartridges that increase the breathing time of existing self-rescuers and new â€hybrid†units that rely on filters to deal with poor air quality-will be developed in the next two years.

Shuttle Shock

With a little luck, Discovery will fly again this month Thunderstorms forced NASA’s last space shuttle fight to land at Edwards Air Force Base in California rather than at the spacecraft’s launch site in Florida. Five days later-on August 14, 2005-lighting struck at Edwards too. In this photograph, taken that day, the shuttle is parked in a gantry-like structure called the Mate-Demate Device, used to hoist the spacecraft off the ground and lower it onto a 747 airplane for a piggybank trip home to Cape Canaveral. There, Discovery was readied for its July mission to the International Space Station, in which the crew will deliver supplies and test methods for repairing in-flight damage to the craft.

Star Burst

Renderings depict eight sequential moments of Cassiopeia A´s 325-year-long explosion.

Something Fishy

New to the London Aquarium: a robotic carp Swimming alongside its living counterparts at the London Aquarium, the new 20-inch-long “robo-carp” uses artificial intelligence and an infared sensor inside its mouth to detect and avoid obstacles. Like real fish, it generates forward thrust by undulating its tail. Engineered by scientists at the University of Essex in England, the battered-operated fish serves as a decorative prototype for future autonomous underwater vehicles that will be tasked with arduous missions, such as sniffing out underwater and leaky oil pipes.

Carrier Reef

The retired U.S.S. Oriskany is now host to fish and divers Five hundred pounds of plastic explosive sent this 32,000-ton aircraft carrier to the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico in May, forming the largest intentional man-made reef in history and marking the inauguration of a Navy program to turn old ships into coral reefs. To meet EPA standards for sea disposal, the 888-foot carrier was stripped of oil, paint and asbestos, at a cost of $8 million. It worked: The scuttle didn´t even leave a slick on the surface. The hull of the craft now rests at 212 feet, too deep for casual scuba divers, though the higher superstructure should be fair game. You have plenty of time to plan your trip-the Oriskany won´t disintegrate for hundreds of years.

Blue Vision

Marine biologists team up with NASA to conduct the first global survey of coral reefs This satellite image of Hawaii´s Pearl and Hermes Atoll was taken by NASA´s Landsat spacecraft as part of the first-ever global survey of coral reefs, com-pleted earlier this year. An international group of scientists used 1,800 Landsat images taken over a four-year period to assess the health of the world´s reefs. The diagnosis wasn´t good. Although the study determined that 19 percent of reefs are located within designated marine refuges, most of those areas are not actually protected from human activities and, like nonprotected areas, are suffering the effects of human pollutants and destructive fishing practices. One piece of good news: This 400-square-mile atoll is part of the 140,000-square-mile Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Marine National Monument, which became the largest marine refuge in the world when it was created in June.

Thin Diesel

A British backhoe manufacturer takes its new engine to an unlikely work site: Utah´s Bonneville Salt Flats Past owners of the notoriously wheezy diesel Rabbit will find it hard to believe, but this blurry streak is also powered by a four-cylinder diesel. Two of them, actually: one for the front wheels and one for the rear. Built for use in front-loaders and forklifts, the 4.4-liter engines were specially tuned to 750 horsepower each by U.K. construction-equipment company JCB as part of an effort to set a new speed record for a diesel-powered car. It paid off. On August 23, Andy Green-holder of the current overall land-speed record of 763 mph-piloted the svelte, ice-cooled machine to a new record in the Utah desert, averaging 350 mph in two 11-mile runs.

Solar Sailing

Testing a sail that turns sunlight into rocket fuel In a test chamber at NASA Glenn Research Center´s Plum Brook Station in Sandusky, Ohio, engineers show off a 20-by-20 meter solar sail that automatically unfurls when its four support tubes are inflated. Built by L’Garde, Inc., of Tustin, California, the sail is made of Mylar less than one tenth the thickness of a trash bag. It´s designed to deflect photons from sunlight to propel a spacecraft forward with little fuel. A larger version of the sail is a candidate for NASA’s Space Technology 9, a mission for experimental technologies that could fly in the next five years.

Yellow Lab

The JCB Dieselmax´s 350 mph smashed the previous diesel record of 235 mph, set in 1973.

Carrier Reef

The retired U.S.S. Oriskany is now host to fish and divers Five hundred pounds of plastic explosive sent this 32,000-ton aircraft carrier to the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico in May, forming the largest intentional man-made reef in history and marking the inauguration of a Navy program to turn old ships into coral reefs. To meet EPA standards for sea disposal, the 888-foot carrier was stripped of oil, paint and asbestos, at a cost of $8 million. It worked: The scuttle didn´t even leave a slick on the surface. The hull of the craft now rests at 212 feet, too deep for casual scuba divers, though the higher superstructure should be fair game. You have plenty of time to plan your trip-the Oriskany won´t disintegrate for hundreds of years.

Tossed In Space

What to do with an old space suit? Turn it into a satellite Part laundry bag, part experimental satellite, this repurposed Russian space suit now orbiting Earth at 17,500 miles an hour, may be among history’s most creative recycling efforts. SuitSat, as the makeshift craft is called, is the brainchild of a Russian ham radio operator who saw an opportunity to do something useful with old space suits on the cramped International Space Station. To test the satellite idea, ISS crew members stuffed a suit with a radio transmitter, some digitized recordings of children’s voices, three batteries and, oh what the heck, old laundry. Then they tossed the whole thing overboard. An antenna mounted on the helmet broadcast the voices for two weeks in February to amateur radio operators worldwide before they suit’s batteries died, leaving it to orbit in Earth in silence until this August, when it’s expected to burn up in the atmosphere. SuitSat-2 is scheduled to fly next year.

Gross Anatomy

The world´s fastest body scanner sees it all Not so long ago, a detailed view of the body´s delicate innards required two things: a cadaver and a scalpel. Today, high-powered rotating x-ray machines can visualize bones, organs and blood vessels down to 0.4 millimeter in just seconds, death not required. One such machine is the new $2.3-million Somatom Definition scanner, developed by Siemens and set to debut in the U.S. this spring. It generated this vivid scan of a 65-year-old heart patient in just 17 seconds. Doctors used the images to rule out arterial blockage, saving the patient a trip to the operating room.

Fast Fueled

Powered by vegetable oil and animal fat, a sleek new boat aims to circumnavigate the globe in record time New Zealand engineer Pete Bethune had a grand plan: Bring attention to the potential of biodiesel by building an innovative powerboat capable of setting an overall speed record for world circumnavigation. And he had a gruesomely flamboyant first step: Suck fat out of his own body to provide some of the fuel. Unfortunately, the quarter of a pound Bethune had lipoed created only enough biodiesel to power his one-of-a-kind boat, christened Earthrace, about 300 feet. To make the trip around the world, the 78-foot tri-hull will need 35,000 gallons of fuel (at its cruising speed of 15 to 25 knots, it gets about a mile a gallon). If all goes as planned, Bethune will raise the remaining $400,000 he needs to fund the voyage by March and set off on his 65-day quest. â€I look forward to getting on the water,†Bethune says, â€and proving to the world that renewable fuels are synonymous with power and performance.â€

Shining Sea

Glowing algae light up California´s largest lake Taken on the southern shore of the Salton Sea, this eight-second exposure is lit from three sources: the moon overhead, the lights of a nearby power plant, and mysterious bioluminescent algae blooming in the water. Waves agitating the single-celled organisms cause a chemical reaction within them that releases energy in the form of light. San Diego State University biologists collected the first samples of the glowing algae from the lake in January and have identified them as dinoflagellates in the genus Alexandrium, a kind of algae typically found along ocean coastlines. The scientist’s next tasks are to determine whether the algae are a new species and to figure out what’s fueling their recent growth.

The Macro View

This millipede [magnified 7.5 times] is the leggiest of 12 specimens plucked from the California soil.

Sun Burn

Solar storms can knock out power on Earth.

New satellites will help us predict where and when Spewing billions of tons of plasma millions of miles into space, the sun´s eruptions, like this explosion captured by NASA´s SOHO probe, can be strikingly beautiful. But when they result in what scientists call coronal mass ejections-think seething bubbles of flung-off plasma-they can short-circuit satellites and trigger powerful magnetic shock waves that result in electrical power failures on Earth. NASA´s $540-million STEREO mission, whose two satellites were scheduled to launch in late August, is designed to capture 3-D images that identify Earth-bound solar storms days before their effects reach us. Positioned at points ahead of and behind the Earth in its orbit, the satellites will work like a pair of eyes to more precisely measure a storm´s size and location-and let us identify it in time to take action and prevent damage.

Afragola is Burning

As Naples’s garbage crisis worsened, fed-up and desperate residents resorted to arson–setting more than 100 fires some nights–overwhelming the fire department and leeching harmful chemicals and toxins into already polluted air. Deemed an “ecological and health disaster” by President Giorgio Napolitano, trash crises are common in Southern Italy but have recently increased and worsened. This summer’s is the worst yet, with 10-foot-high piles of refuse lining the streets for weeks now while old dumps max out and new ones are stalled from construction by a weak local political system and a powerful local mafia.

Starborn

Thirteen hundred light-years away, a three-million-year-old supernova explosion launches a cluster of new stars. Captured by NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope, the birth is visible because of infrared imaging that bypasses dense cloud formations to detect heat-radiating stars, galaxies and planetary systems. As the stars emerge from the Orion constellation, they heat surrounding dust particles (seen in the orange-red areas) and eventually become surrounded by cosmic gas and dust (as are the young pink stars near the top).

by John B. Carnett

A select from our favorite aviation images by staff photographer John B. Carnett

Low Rider

Kolodziejzyk circled the Eureka, California, track 1,800 times.

Water Buggy

A prototype watercraft is designed to go almost anywhere, bump-free It´s known as Proteus, and its performance is just as unusual as its appearance. The creation of California company Marine Advanced Research, this leggy craft is the helicopter of boats, explains designer Ugo Conti, who says Proteus clones could someday be used for quickly deploying research equipment to far-flung locales or for ocean search-and-rescue operations. The range of conventional craft is limited by their ability to take the pounding of huge swells in the open ocean and by the depth of the boats´ draft in shallow water. Proteus´s catamaran-style hulls displace only 18 inches, so it can operate safely close to shore. And the vehicle is designed to surf on top of the waves, rather than cut through them, allowing it to travel safely and efficiently in rough seas. The ride can´t be beat: The cockpit is suspended on four aluminum legs attached to the hulls by titanium springs. Which means no bumps-and a view 12 feet above the waves.

Low Rider

Kolodziejzyk circled the Eureka, California, track 1,800 times.

Blue Crush

In Australia, bluebottle jellyfish invade in striking numbers Sailing ashore on blustery northeast winds, vast armadas of half-foot-long bluebottle jellyfish took Australia´s Gold Coast beaches by storm this year. The smaller, electric-blue cousin of the Portuguese man-o´-war (both species are technically polyps) commonly blows in to southern beaches during the summer months–November to February, Down Under–in dense packs. (This flotilla was photographed on Terrigal Beach in New South Wales.) But seldom have they arrived in such nettlesome droves: In a single January weekend, Queensland lifeguards treated 600 stings, a stunning increase over the 476 stings recorded for that entire month in 2006 (though painful, stings are almost never deadly). It´s unclear whether there has been a population spike among the sail-shaped, gelatinous invertebrates or if the wind patterns are simply bringing more of them ashore, says Lisa-Ann Gershwin, a jellyfish expert at James Cook University in Queensland. â€They live way out in the central gyres in the middle of the great oceans,†she explains, â€but so far nobody´s bothered to go out there and count them.â€

![A Milky Way supernova is providing clues to the origins of planets-and people Cassiopeia A, the remnants of the most recent star to explode in our Milky Way galaxy, is only 10,000 light-years away, close enough for astronomers to get a detailed look at it through the Hubble Space Telescope. By comparing this composite image of Cas A with one taken nine months earlier, scientists have discovered that the glowing cloud of debris left behind by the supernova is not expanding uniformly, as was once assumed. Instead two opposing jets of material are moving at 32 million mph, about 20 million mph faster than the rest of the debris [in this image, one stream extends from the upper left side of Cas A]. Another surprise: This view, which highlights different elements by color (for example, oxygen is shown as green), shows that materials of similar chemical composition remained clumped after the explosion. Supernovae are a major source of all elements heavier than hydrogen and helium and the primary source of heavy elements like iron. These scattered elements eventually coalesce into new stars and planets. They are also what we´re made of.](https://www.popsci.com/uploads/2019/03/18/GEMPH5LEGS6OX2LF5BKZGQAH2I.jpg?auto=webp&optimize=high&width=100)

![This millipede [magnified 7.5 times] is the leggiest of 12 specimens plucked from the California soil.](https://www.popsci.com/uploads/2019/03/18/OGS46FYME3IMNZGQNGOCCTCKFI.jpg?auto=webp&optimize=high&width=100)