Where do trans fats come from, and why are they so bad?

Will somebody please tell me why my cookies are evil?

American consumers are finally winding down their love-hate relationship with trans fats. Yesterday, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced that manufacturers must stop adding trans fats to foods by 2018. This hard line has been building for a number of years—in 2013 the FDA announced their intention to start a phase-out like this one. Dietary guidelines suggest that diners avoid trans fats as much as possible, and restaurants have been removing them from their menus. But what’s so bad about them, anyway?

What is a trans fat?

Chemically, a fat is a series of three fatty acids, or chains of carbon atoms, connected by one molecule of glycerol. The structure of the atoms and molecules can vary slightly, which changes how the fats affect your body. Cis fats have hydrogen atoms bound on the same side of the carbon in the fatty acids, which gives the chains a bend, and causes the fat to be liquid at room temperature.

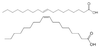

In a trans fat, the hydrogen atoms are bound on opposite sides of the carbon in the fatty acids, giving the acids a straight structure. This change may seem small, but it totally changes the fat’s physical properties–trans fats have a higher melting point than cis fats and can stack on top of each other, which makes them solid at room temperature. And unlike cis fats, trans fats aren’t so good for you and have been shown to cause higher levels of “bad” cholesterol in people that eat them.

Elaidic Acid and Oleic Acid

How are they made?

In a process called hydrogenation, manufacturers heat up a liquid oil with hydrogen atoms and a catalyst. When fats are fully hydrogenated, they have the maximum possible number of hydrogen atoms bound to them, and they become solid. These saturated fats, found in some meat and dairy products, aren’t actually that bad for you . But when the oils are only partially hydrogenated to create semi-solid oils like margarine, trans fats are created, which have worse effects on the body. Some trans fats also occur naturally in food, but people who talk about dangerous trans fats are almost always talking about the ones that were created artificially.

Why do food manufacturers love them?

When you need a fat that’s semi-solid at room temperature, partially hydrogenated fats are really cheap–cheaper than using butter or another fat with the right characteristics, such as coconut oil or lard. But they also make the food last longer on shelves; unlike liquid fats, trans fats take a long time to break down. Many processed foods use trans fat-containing oil in some capacity—cookies and cakes are baked with it, potato chips or microwave popcorn are fried in it. Some types of margarine are just a solid version of these oils.

What makes them bad for you?

Because of their particular chemical structure, trans fats are hard for your body to metabolize, so they aren’t a good source of energy. Since your body can’t really use them, they sit in the fat tissues around the body, hindering its ability to efficiently break down and use other proteins or fats that could help keep it running. As a result, trans fats have been found to raise your LDL (“bad”) cholesterol and lower your HDL (“good”) cholesterol, making people who eat trans fats more likely to have type 2 diabetes, stroke, or heart attack.

For a long time there was no scientific consensus on whether or not trans fats were really as bad as they seemed. Studies intended to determine the long-term effects of these fats on the human body found that they caused significant damage to the heart and arteries. The FDA kept asking for more research, more information, before taking a strong stance, likely because of pressure from the food industry. But in 2013 the FDA was forced to act when a university professor sued the organization for not banning trans fats sooner.

How will the ban change food?

Trans fats have already been on their way out for many food manufacturers—sales on foods containing trans fats dropped by 78 percent from 2003 to 2012, the FDA estimates, in part because the foods have to be labeled as such.

The food industry is happy that the ban won’t come into effect for another three years, giving them time to find viable alternatives, according to the New York Times. Researchers are looking into what those options might be. Some are finding new uses for naturally stable oils made from corn and palm, and others are tweaking the chemical structure in fish oils so that the final product has properties like partially hydrogenated oils, but is better for human health.

But so far, phasing out partially hydrogenated oils hasn’t necessarily made food more healthful—one expert estimates that saturated fats, which also raise bad cholesterol levels, have become more common in baked goods between 2005 and 2012.

If food manufacturers get their way, some products may still contain artificial trans fats; they’re fighting to keep trans fats in a handful of products. But regardless, the ban stands to do more good than harm. The search for alternatives could inspire the invention of oils that could be more eco-friendly fuels. It’s a good move even from a financial perspective: The FDA estimates that, though the ban will probably cost $6 billion to put into effect, it will save $120 billion in health costs over 20 years.