British Scientists Want Permission To Genetically Edit Viable Human Embryos

The conversation about CRISPR is moving fast

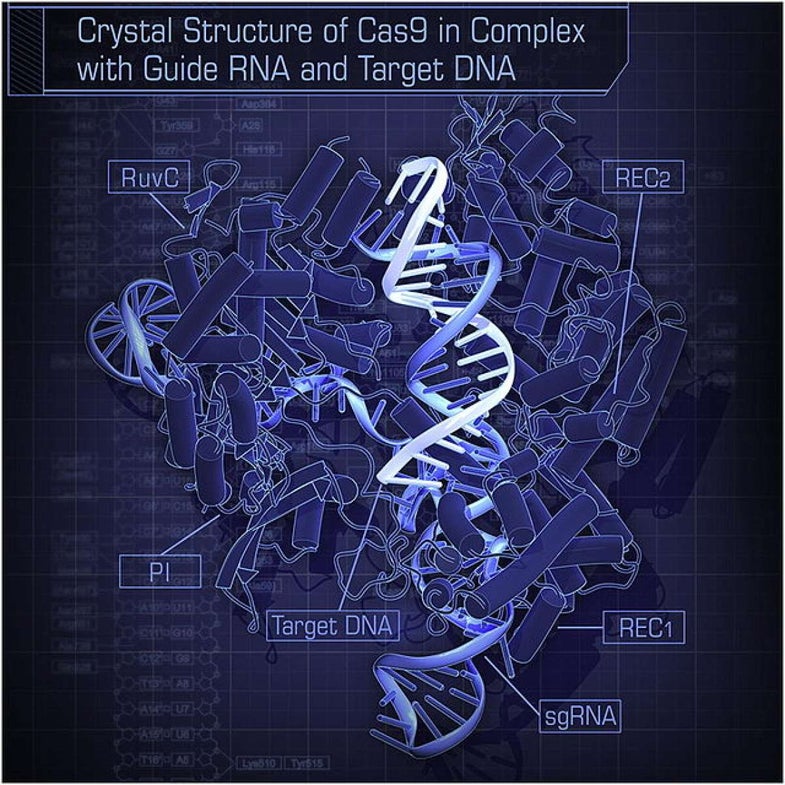

While scientists around the world continue to debate the use of the CRISPR/Cas9 system, the tool capable of precisely editing DNA on the genomic level, British scientists working at the Francis Crick Institute in London announced today that they have applied for permission from the United Kingdom’s fertility regulator (the UK Human Fertilization & Embryology Authority) to use this technique on viable human embryos. If granted, this would allow them to directly study humans’ earliest stage of development and would mark the first approval by a national regulatory body to employ the CRISPR/Cas9 system on viable human embryos.

The use of the CRISPR/Cas9 system remains a controversial issue. This new announcement comes only a few months after an op-ed was published in Nature cautioning against its use, and after Chinese researchers reported they had indeed successfully employed the CRISPR/Cas9 system on non-viable human embryos to remove a part of the gene that causes a genetic blood condition called beta thalassemia.

Kathy Niakan, a group leader at Crick and lead author of the research, says her and her team plan to use CRISPR/Cas9 for basic research, with no intention of a clinical application. Further, the viable embryos would only be studied for two weeks and, by UK law, cannot be implanted for a successful pregnancy. However, the information gathered by this basic research could have broad clinical implications, particularly to improve the success rate for healthy embryonic development after in vitro fertilization as well as potential for use in stem cell research, according to the press release. Crick’s announcement was first reported in an article in The Guardian.

The use of this research in even non-viable embryos has been intensely regulated. The U.S. National Institutes of Health reaffirmed its ban on research that involves gene editing of human embryos in late April of this year, shortly after the Chinese researchers reported their use of CRISPR/Cas9 in non-viable embryos. Thus even asking permission to use this research in viable embryos is likely to spark another gigantic wave of discussion as to whether CRISPR/Cas9 should be used on any human embryos at all. Some argue that editing the human genome could have unintended consequences that could be passed down to future generations, but at the same time, many scientists believe CRISPR/Cas9 could be an important tool for treating and even preventing certain diseases, if given the proper basic research.

Niakan told The Guardian:

Whether or not this new research proposal will be conducted remains under discussion. Nevertheless, in the wake of this surge in interest and because of the broad implications the CRISPR/Cas9 technique could have, scientists around the world advise that before any further research gets underway, conversations need to be had. On September 14th of this month, scientists from the United States, China, and Britain announced that they plan to host an international summit to discuss the future of human gene editing, Reuters reported. That meeting is currently scheduled to take place in Washington, D.C. on December 1-3 of this year.