Brain Scans Could Identify Depression Before Symptoms Emerge

Which could lead to more effective treatments

Depression is far more complex than a “chemical imbalance” in the brain—researchers have found that biology, psychology, genetics, and environmental factors all play a role in the onset and expression of the condition. Now researchers think they’ve come closer to identifying those individuals that are most susceptible to depression before their symptoms set in—by taking brain scans from children at risk of developing depression and comparing them to those from children with no family history of depression, the researchers have pinpointed differences in the way information is transmitted in the brain, according to a study published online last month in the journal Biological Psychiatry. Understanding those differences might help scientists diagnose and treat depression more effectively.

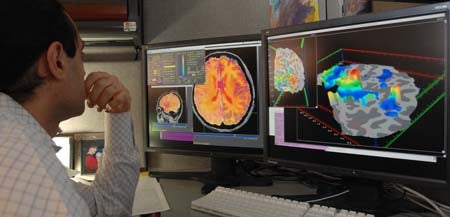

In the study, the researchers hooked up 43 children between eight and 14 years old to an fMRI machine, which detects the movement of blood in the brain. 27 of those children were considered at risk of developing depression because others in their families have the condition. The researchers were most interested in something called resting-state functional connectivity, or the patterns of communication found naturally within the brain when it’s not trying to complete a particular task.

They found that the children most at risk of developing depression had a particularly strong connection between the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex and the default mode network, a pattern that had already been seen in depressed adults, according to a press release from MIT. In at risk children, the researchers also found a strong connection between the amygdala and the inferior frontal gyrus, necessary to modulate emotion, and a weaker connection between the frontal and parietal cortex, used in thinking and decision making.

By blinding the results, the researchers found that these patterns enabled them to easily distinguish between the at-risk children and those without any family history of depression. That indicates that fMRI results like these could help doctors identify and treat depression before it sets in, which could prevent the disease from progressing since one bout with depression makes a person much more likely to have another one in the future. Further understanding of these strong and weak connections might help researchers identify the underlying neurological cause for depression, which could lead to better treatments.

Since depression is so complex, having a genetic predisposition doesn’t mean a person will develop depression, and people without depression in their families can develop it, too. That, combined with the small sample size, means that this study doesn’t give researchers exceptionally robust information about these connections. But it’s an interesting first step towards better diagnosis and treatment for depression.