Mercury Astronaut Scott Carpenter and the Controversy Surrounding Aurora 7

This past May, I went to Spacefest V in Tucson, Arizona, one of the few events where you’d do well...

This past May, I went to Spacefest V in Tucson, Arizona, one of the few events where you’d do well to pay special attention to the elderly men you meet in the hall because they just might have walked on the Moon. The group of kids I saw barreling down the breezeway one afternoon in their haste to get to the pool certainly wasn’t aware that a group of historic men were in the building. And neither were their parents. The whole group was just careful to get past the elderly man on the motorized scooter without knocking into him. None of them gave him a second glance. That man was Scott Carpenter, the second American to orbit the Earth.

Scott Carpenter was one of NASA’s first astronauts, one of the so-called Mercury Seven. But he’s not the most recognizable name of the group. John Glenn, of course, was the first American to orbit the Earth, and is now the only surviving astronaut of his class. Al Shepard was America’s first astronaut and the only Mercury astronaut to walk on the Moon. Wally Schirra was the only astronaut to fly all three Apollo-era programs – Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo. Gus Grissom led a fascinating career until his untimely death in the Apollo 1 fire. Deke Slayton, grounded in 1962 with a heart condition, led the astronaut office before flying on the 1975 Apollo-Soyuz Test Project mission. And Gordon Cooper set two long-duration flight records on his Mercury and Gemini flights.

Carpenter only flew one mission, a relatively short three orbit Mercury flight on May 24, 1962. And the legacy that has persisted is one of an astronaut disobeying commands, putting the mission – and his own life – in jeopardy. But this is far from a fair assessment. There’s a lot more to the story.

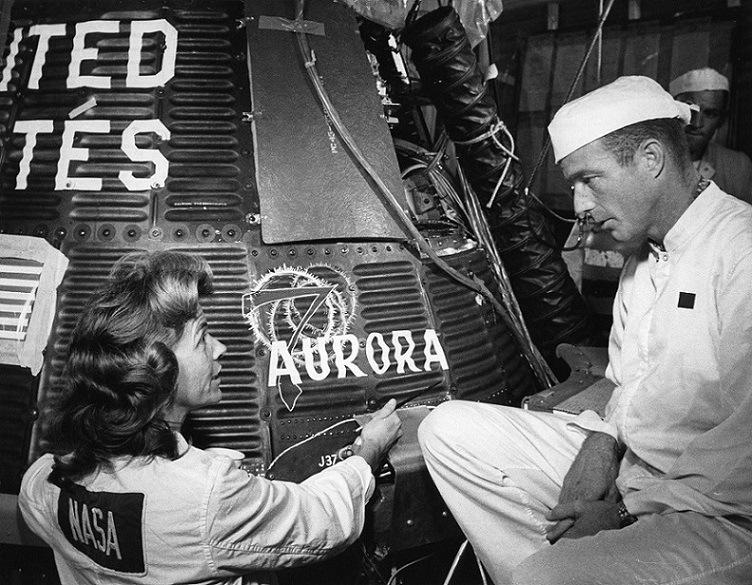

Carpenter getting his suit adjusted before his Aurora 7 flight.

Aurora 7

Carpenter’s flight assignment came as a bit of a surprise to his peers. Deke Slayton was scheduled to fly after John Glenn but was pulled from the flight rotation with atrial fibrillation. But rather than give the flight to Slayton’s backup pilot Wally Schirra, NASA gave it to Glenn’s backup Carpenter. The logic was that Carpenter, who had been training closely with Glenn for months, was the best prepared astronaut the agency had. And in light of the mission’s complexity, this was probably a good decision.

Glenn had proved that an astronaut could be more than just a passenger in space, so with its second orbital mission NASA decided to really push the astronaut into a central role. Building on the experience gained from Glenn’s flight and seeking to gather as much scientific data as possible, Carpenter’s flight plan quickly filled up.

His mission was packed with science goals, experiments, and a continual transfer of biomedical data sent to mission control. Carpenter would also have more control over his spacecraft. By combining the yaw-roll maneuvers, NASA wanted the astronaut to orient his spacecraft to see sunrises, day and night horizons, Earthly landmarks, and find certain stars as navigation references. The agency also wanted him to flip his spacecraft upside-down placing his head towards the Earth for a disorientation experiment. Other science experiments included releasing a multi-colored balloon tethered to the capsule as a test of depth perception in space, observing the behavior of liquid in microgravity, using a specialized light meter to measure the visibility of flares on Earth, taking weather photographs through a variety of different filters, and studying the airglow layer.

As launch day neared, Carpenter named his spacecraft Aurora 7. “I think of Project Mercury and the open manner in which we are conducting it for the benefit of all as a light in the sky. Aurora also means dawn — in this case the dawn of a new age.” He also happen to have grown up on the corner of Aurora and Seventh Avenues in Boulder, Colorado.

The Mission

After a 1:15 AM wakeup call, a specially prepared breakfast of filet mignon, poached eggs, strained orange juice, toast, and coffee, and a physical examination, Carpenter was covered in biomedical sensors and snugly cased inside his silver flight suit. A series of holds due to fog stalled an otherwise flawless prelaunch countdown until finally, at 7:45 AM, the Atlas bearing Aurora 7 roared to life and carried Carpenter off the Earth.

Carpenter’s first order of business once in orbit was to turn the spacecraft around to its normal backward flying attitude, one that promised an easy retrofire burn and return to Earth. And he was tasked to do this manually; Glenn had let his onboard computer make this manoeuver and it had cost him a significant amount of fuel. And in spaceflight, fuel is among the most precious commodities.

The Mercury spacecraft was limited in its abilities. It could keep an astronaut alive, and send him back to Earth with one burn of its three retrofire engines, and chnage its attitude by pivoting around its three axes. The main attitude control system was the automatic stability and control system (or ASCS) that had twelve thrusters feeding off 32 pounds of hydrogen peroxide fuel. The computer could control this system or the astronaut could forcibly take control using fly-by-wire commands. There was a secondary, manual control system made of 6 thrusters feeding off 23 pounds of fuel. Separating the systems and their respective fuel stores was one of the redundancies NASA incorporated into the spacecraft, but it wasn’t foolproof. Danger lay in a problem called dual authority control: it was possible for an astronaut to switch to fly-by-wire without turning off his manual system, drawing fuel from both tanks.

Carpenter looks into his Aurora 7 spacecraft before launch.

But there were more potential problems than a limited fuel store. A series of instruments monitored the capsule’s orientation and fed data to the onboard computer for the automatic stability system to maintain it’s attitude. Any flaw with these instrument readings and the computer would lose its bearings.

Twisting Aurora 7 around in orbit while trying to follow his packed flight plan, Carpenter didn’t realize his horizon scanner, the instrument that optically fed pitch attitude information to his onboard computer, was off by about 20 degrees. He also didn’t realize that in switching between fly-by-wire and manual control as prescribed by his flight plan he’d engaged dual authority control six times during his first orbit. By the end of his second orbit, Carpenter’s fuel supply had dropped to worryingly low levels – about 42 percent in the manual tanks and 45 percent in the automatic tanks. Houston told Carpenter that 40 was the magic number. As long as he had 40 percent fuel in both tanks, he’d be ok for retrofire on time and maintain his spacecraft’s orientation throughout reentry. Any less, and the mission might end in disaster.

Carpenter didn’t seem concerned about his low fuel levels, but Flight Director Chris Kraft was. Watching the numbers in both tanks drop steadily as the flight progressed from his console in Mission Control, Kraft sent a constant stream of orders via capcoms for Carpenter to conserve his fuel. Aurora 7’s computer, too, was worried about the dropping fuel levels. After the first orbit it gave Carpenter a low fuel warning light. He promptly covered it with a piece of tape so it wouldn’t bother him.

Carpenter proceeded with scheduled experiments and entered a period of drifting flight in his third orbit to conserve fuel. And coming over Hawaii on his last pass, he had managed to maintain that magic 40 percent fuel in both tanks. But he was so focused on changing the film in a camera for a last round of pictures and investigating the “fireflies” that had puzzled Glenn on his flight that he was late beginning his preretrofire checklist. It was at this point, when he needed to move quickly through vital steps, that Carpenter noticed the flaw with his horizon scanner. The automatic stabilization system couldn’t hold the 34-degree pitch and zero-degree yaw attitude he needed for reentry. Trouble shooting this new problem set him further behind, and when he engaged his fly-by-wire control mode, he forgot to switch off the manual system. For 10 minutes, both systems were burning fuel.

Carpenter managed to get Aurora 7 aligned for retrofire, but it wasn’t a perfect orientation nor was it on time; the spacecraft was canted about 25 degrees to the right and the burn began three seconds late. And it was only after retrofire that Carpenter noticed both control systems were drawing fuel; by this point, the manual system was empty and the automatic system had just 10 percent left. Using fly-by-wire sparingly to keep the horizon in sight, Carpenter managed to hold Aurora 7’s attitude. The remaining fuel was consumed by the auxiliary damping mode that minimized oscillations as the spacecraft fell through the atmosphere.

At 15,000 feet, Carpenter armed his main parachute and deployed it manually at 9,500 feet. He landed softly in the Atlantic some 250 miles from his intended splashdown point. After learning from NASA that the recovery crew were at least an hour away, Carpenter elected to leave the cramped, hot capsule. He climbed through Aurora 7’s neck, dropped a life raft into the ocean, and plopped himself down. Untroubled at the thought of being alone in a plastic raft in the Atlantic Ocean, Carpenter took the time alone to reflect on the flight. When recovery planes arrived and Navy divers swam up to the raft three hours later, a serene Carpenter offered them some food from his survival kit.

Carpenter’s Tarnished Legacy

Though Carpenter knew he was alive and well, Kraft didn’t, nor did the rest of the country; it wasn’t immediately clear whether NASA’s fourth mission would be its first fatality. When it turned out Carpenter was alive, Kraft was relieved but livid. He blamed the mission’s problems on Carpenter’s poor performance, saying the astronaut had ignored repeated instructions to conserve fuel and check his guidance instrumentation. And as he wrote in his 2001 memoirs, Kraft swore an oath then and there that Carpenter would never fly in space again. And he didn’t. Carpenter took a leave from the astronaut corps in 1963 before leaving NASA entirely in 1967.

Glenn and Carpenter shaking hands before Aurora 7’s launch.

Kraft has maintained his position on Carpenter’s guilt since 1963, and he isn’t alone. Max Faget who designed the Mercury capsule called Carpenter a better poet than astronaut. Last year I met former mission control technicians Jerry Bostick and Glynn Lunney, and asked them about the stories of NASA writing mission rules mid-way through flights because they were all learning as they went. They told me this wasn’t entirely true. Mercury was certainly a learning experience but there was always a flight plan in place, though some people, they added in a whisper as they gestured towards Carpenter at the next table, didn’t follow the rules.

The other Mercury astronauts, too, with the exception of Glenn, sided with more with Kraft than with Carpenter. Somewhere along the way Aurora 7 was nicknamed “Stigma 7” for the shadow it cast over the astronauts’ collective reputation. Wally Schirra, next in line to fly, made it his personal goal to prove that an astronaut could be more of a help than a liability in space. He named his spacecraft Sigma 7 to reflect his goal of engineering perfection, and on October 3, 1962, he drifted in space for the bulk of his six orbits and landed incredibly close to his splashdown target point with plenty of fuel to spare. Schirra’s mission didn’t teach NASA about space, but it returned what was then vital engineering information.

The controversy surrounding Carpenter’s flight speaks to a bigger problem NASA was facing at the time. In the spring of 1962, with two suborbital flights and one orbital mission under its belt, the space agency hadn’t figured out just how men and machine should relate in space. On one hand were the technicians in Mission Control monitoring every aspect of a flight in real time, plotting reentry paths and keeping tabs on when and where they could bring the spacecraft home safely if an emergency arose. On the other hand were the astronauts, all experienced fighter pilots used to testing new aircraft in adverse conditions and accustomed to make life-saving decisions in a split second. The orbiting astronaut wanted to be in command of his mission, but so did the Flight Director. Often the fight for control was tempered by the astronaut and Flight Director’s mutual focus on engineering data. But not in Carpenter’s case. His focus on in-flight experiments left him at odds with Kraft.

That some controversy over the flight endures shouldn’t continue to call Carpenter’s competence or Kraft’s controlling nature into question. Rather, questions over Aurora 7’s imperfect fuel usage and overshot landing should be seen as a case study. It’s a brilliant example of how a space agency learned by doing in the early years of the space age and how two ways of managing a mission – one with engineers in charge on the ground and the other with pilots in charge in the air – came to a head. It’s also an example of how different types of people approached the business of spaceflight – with an unwavering focus on engineering precision on Kraft’s part and with a pilot’s judgement and very human appreciation of the beauty and fragility of our planet on Carpenter’s part. Unfortunately for Carpenter, Mercury was not a program for starry eyed astronauts.

Me, pretty starstruck, shaking hands with Carpenter. November 2012.

Cooperation between astronauts and mission control came slowly after Aurora 7’s flight. It wasn’t really until the Gemini program when astronauts got a more central role due to the complexity of these rendezvous mission that tensionseased and a better working relationship was established.

A Real Legend

I met Scott Carpenter in November 2012 at an Astronaut Scholarship Foundation event. I can’t remember exactly what I said to him, though I’m sure it was some stumbling remark about how honoured I was to meet one of the nation’s first astronauts. I had so many questions, but as soon as I sat down next to him I couldn’t think of a single one. Because whatever his reputation, he’s still one of the elite group of men who stood on the forefront as the world entered the space age, and these are the men I’ve been reading about for more than two decades. And he couldn’t have been nicer, posing for pictures and signing my beat up copy of This New Ocean, NASA’s official history of the Mercury program that has become a very prized possession.

Mine isn’t a great story, but I’m very happy that I at least have a story about meeting Mercury astronaut Scott Carpenter. He died on October 10, 2013, at 88 years old.

_Sources include: the Aurora 7 Mission Report; the Aurora 7 Mission Transcript; This New Ocean by Swenson, Grimwood, and Alexander; Flight: My Life in Mission Control by Chris Kraft; and For Spacious Skies by Scott Carpenter with Kris Stoever. _