You shouldn’t be too worried about the huge asteroid that’s about to fly right past us

Potentially hazardous objects are rarely all that hazardous.

An asteroid named Florence will pass by Earth on September 1, and it’s the largest one to fly by since NASA started keeping records. But except for amateur astronomers and some NASA scientists, most of us will be completely unaffected.

At 4.3 kilometers wide, Florence would devastate a significant chunk of our planet if it collided with us. A task force on Near Earth Objects has estimated that a rock that size would kill 1.5 billion people. But Florence won’t get anywhere near close enough to do that, just like the many ‘close calls’ we’ve had with large celestial objects in the past. We keep hearing about how dangerous an asteroid collision could be, yet we never seem to be in any real danger. What gives?

‘Potentially hazardous objects’ carry a small potential for an enormous hazard

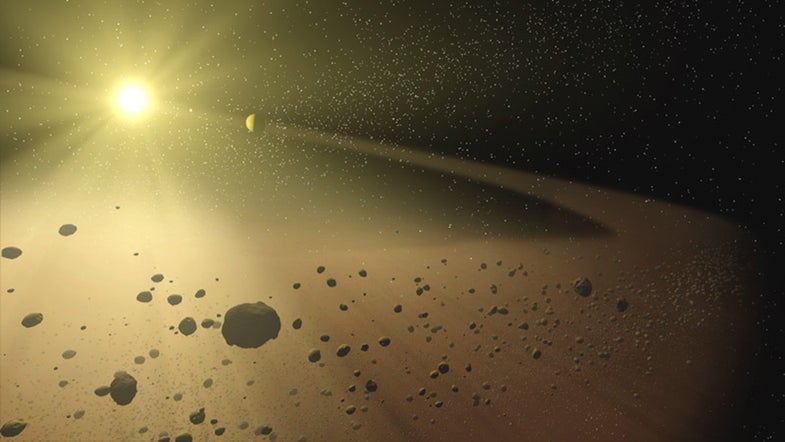

Space is big. Really big. This should go without saying, but it’s worth remembering just how vast it is. A 4.3 kilometer asteroid sounds enormous, and it seems like it wouldn’t take much for a rock that large to unexpectedly run into Earth. And it’s not just visits from Aunt Flo we need to worry about—there are about 1,400 objects that cross our orbit that are capable of causing major problems. Look at them all:

It looks like we should be running into them all the time. But both the Earth and those rocks are moving, meaning the odds that our planet and any particular asteroid would happen to be in the same place at the same time are pretty miniscule. There’s just so much emptiness between every object in our solar system that the odds of a major impact in the 21st century are just 0.0002 percent. And the odds of a global event—like the crash that killed off most of the dinosaurs—are even tinier.

So why do scientists bother to keep track of all those potentially hazardous objects? It’s not because they’re very likely to pose a danger, but because if they were to crash into us, the effects could be catastrophic. An object just one kilometer (just over half a mile) in diameter would put a quarter of the planet’s population at risk. Researchers keep talking about how to prepare for an asteroid collision because they know that an impact of some kind, somehow, is basically inevitable. There are too many potentially hazardous objects for it to never happen. But that doesn’t mean that every flyby is dangerous. Most aren’t.

If an asteroid were actually likely to hit us, we would have a few options

Technically speaking, right now we are woefully underprepared for an asteroid collision. If scientists found out that one were likely to hit us tomorrow, there’s basically nothing we could do but try to get people out of the way of the impact site.

But if we had several years of warning time, we would probably be okay. That’s why scientists keep track of every single potentially hazardous object: time is our only hope. There are already multiple ideas for how to deal with a large rock hurtling towards us, but they all require adequate prep time.

All of the potential plans fall into one of two categories: either try to break up the asteroid enough that it’s not large enough to cause significant damage, or change the asteroid’s orbit so Earth is no longer in its trajectory. The first category is the easiest, since smashing a spacecraft (plus or minus a bomb) into something else is relatively easy, given enough time to launch it into the proper orbit. The problem is that if the asteroid doesn’t break up enough, the debris will still hit Earth. That’s why some scientists are fans of the other category: slowing down an asteroid just enough to change its trajectory. This option has more finesse, but is logistically more challenging—it requires a higher degree of accuracy.

We’re low-risk for a collision in part because collisions are unlikely, but also because we’ve gotten pretty good at tracking asteroids and comets. We spend millions of dollars building giant telescopes in deserts so that we’ll know way, way in advance if some giant boulder is likely to ram into us. And so as long as we can predict a crash, we’re probably okay. Probably.