MIT Students Claim Astronauts Will Starve On ‘Mars One’ Mission

But CEO Bas Lansdorp says the study used bad data.

PhD students at MIT published a study this week that seems to debunk Mars One’s plan to land humans on Mars by 2025 using existing technology. They say that without dramatic improvements in equipment life, the space colonists, who would have no way to return to Earth, could starve to death.

The students, part of a research group specializing in large-scale multi-billion dollar space programs, used publically available information about the Mars One mission plans to simulate the trip to Mars. They say the problems they uncovered surprised them.

“We tried to keep a completely open mind going into it,” says Sydney Do, one of the researchers on the study. He says the idea of space colonization excites him.

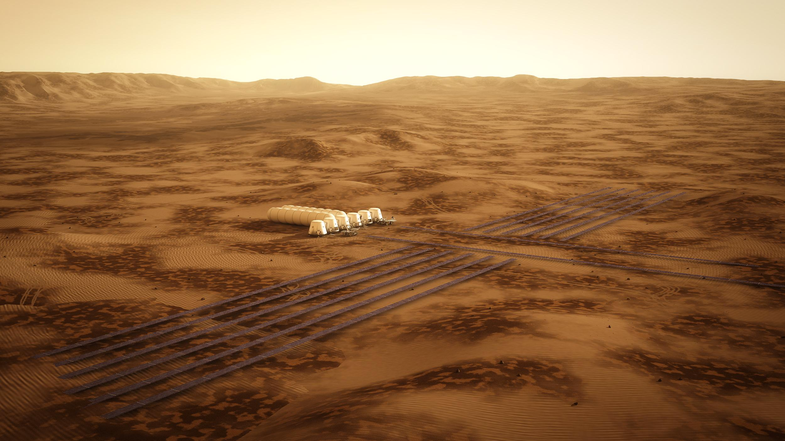

Mars One is looking for 25 to 40 pioneers to leave home forever and live out their lives on the red planet, by growing food and using resources from the Martian environment. The non-profit has recieved more than 200,000 applicants, and there are plans to fund their Mars journey with a global reality show.

“We tried to keep a completely open mind going into it.”

The MIT research was conducted to build a framework for analyzing other space colonization plans. But flaws in Mars One’s plan jumped out as the students ran the numbers.

Mars One expects to grow crops indoors on Mars. Plants produce oxygen–and too much in a closed environment could feed oxygen-sucking fires. Farming would require machines that separate and vent oxygen without losing nitrogen vital to keep up air pressure. But the technology needed to to keep oxygen under control has never been tested beyond our planet, and Do says hardware tested on Earth can fail in surprising ways after liftoff.

A urine recycling system installed on the International Space Station in 2009 returned drinkable water with 90 percent efficiency in NASA laboratories. But on the ISS it broke down. Astronauts lose bone mass in zero-gravity, dumping calcium into their waste, and those deposits gummed up the recycler’s works. The system is up and running again, but at only 70 percent capacity. On a trip with no return flight and limited resupply, such failures could be deadly, especially when they involve maintaining oxygen supply.

But Mars One CEO Bas Lansdorp says the students used incorrect and incomplete data for their study.

“I’ve talked to very knowledgeable people–experts with companies like Lockheed Martin–who tell me these technologies will work,” he tells Popular Science. He says he hasn’t had the time to read the research all the way through, but has looked at the conclusions.

Lansdorp seized on the excess oxygen problem as an example of misplaced alarmism in the research. “This technology has been widely tested on Earth,” he says, “and it’s very well understood.” Similar equipment for scrubbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere has been used in space for years.

But Lansdorp did not have a solution for what Do called the more serious issue uncovered in the research: replacement parts. The students used the failure rates of parts on the ISS to estimate the need for spares in a Mars colony. Without a resupply mission coming for another two years, a huge portion of the mass included in the initial launch would have to be extra materials.

“They are correct,” Lansdorp says, “The major challenge of Mars One is keeping everything up and running.” Repairing equipment and suits on Mars is a problem Mars One has yet to solve. Unmanned supply missions in advance of a second human launch are expected to land on the red planet a few weeks after the original colonists arrive, and Lansdorp suggests the first crew could take those stocks in a pinch.

“We don’t believe what we have designed is the best solution. It’s a good solution,” he says. He adds that Mars One has done its own research with better results, but is not an aerospace company. He hopes future feasibility studies from groups like Lockheed Martin will provide answers. In the meantime, their in-house data is under wraps.

“We’d love to see what data he has and update the model,” Do says.