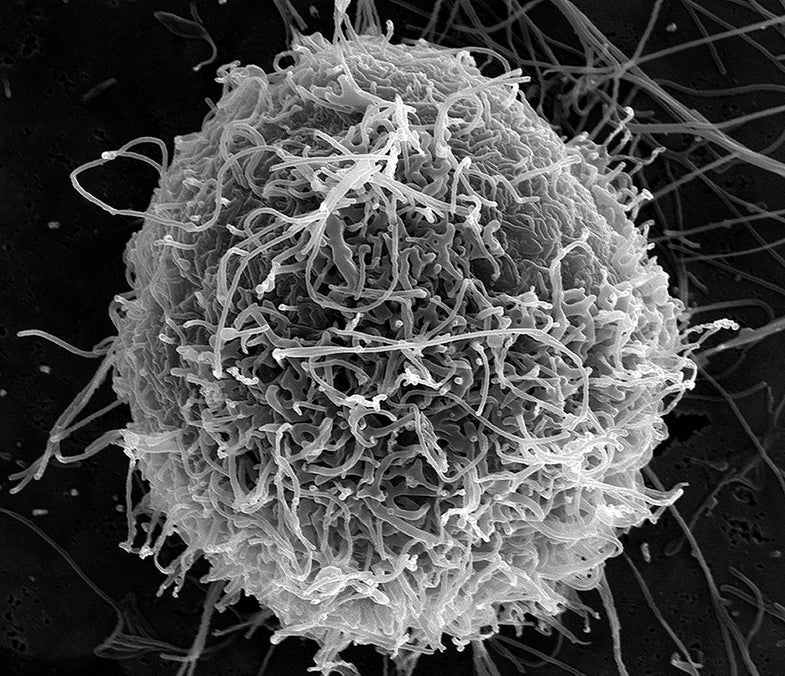

What Happens After Someone Survives Ebola?

Learning more about patients who've recovered from Ebola -- as well as people who are naturally immune -- could save lives.

While most of the recent coverage of the ongoing Ebola outbreak has focused on rising death tolls and a few infected U.S. citizens, other segments of the population have passed mostly unnoticed from the harsh glare of the media spotlight: Survivors, and those who are seemingly immune to Ebola.

People who survive Ebola can lead normal lives post-recovery, though occasionally they can suffer inflammatory conditions of the joints afterwards, according to CBS. Recovery times can vary, and so can the amount of time it takes for the virus to clear out of the system. The World Health Organization found that the virus can reside in semen for up to seven weeks after recovery. Survivors are generally assumed to be immune to the particular strain they are infected by, and are able to help tend to others infected with the same strain. What isn’t clear is whether or not a person is immune to other strains of Ebola, or if their immunity will last.

As with most viral infections, patients who recover from Ebola end up with Ebola-fighting antibodies in their blood, making their blood a valuable (if controversial) treatment option for others who catch the infection. Kent Brantly, one of the most recognizable Ebola survivors, has donated more than a gallon of his blood to other patients. The plasma of his blood, which contains the antibodies, is separated out from the red blood cells, creating what’s known as a convalescent serum, which can then be given to a patient as a transfusion. The hope is that the antibodies in the serum will boost the patient’s immune response, attacking the virus, and allowing the body to recover.

But this treatment method, like all Ebola treatment methods, is far from ideal. To start with, scientists aren’t even sure if it works. In addition, the serum can only be donated to people with a compatible blood type to the donor, and it’s unclear how long the immunity would last. Adding to the confusion, there are several different strains of Ebola, and there’s no guarantee that once someone has recovered from one strain of Ebola they are immune to others.

When Nancy Writebol, one of the survivors of Ebola who was whisked back to Atlanta soon after contracting the virus, was asked by Science Magazine if she would consider going back, she said:

People who survived the disease are of particular interest to researchers, such as those working on the ZMapp drug, who hope that they can synthesize antibodies in the hopes of creating a cure.

But even less understood than the survivors are the people who were infected with Ebola but never developed any symptoms. After outbreaks in Uganda in the late 1990’s, scientists tested the blood of several people who were in close contact with Ebola patients, and found a number of them had markers in their blood indicating they carried the disease, but they were totally asymptomatic—they managed to completely avoid the horrifying symptoms of the disease.

In a letter in the Lancet this week, researchers look into the existence of these asymptomatic patients, and hope that identifying people who are naturally immune could help contain the outbreak as scientists work on developing a treatment. A 2010 study published by the French research organization IRD found that as much as 15.3 percent of Gabon’s population could be immune to Ebola.

“Ultimately, knowing whether a large segment of the population in the afflicted regions are immune to Ebola could save lives,” Steve Bellan, an author of the Lancet letter, said in a press release. “If we can reliably identify who they are, they could become people who help with disease-control tasks, and that would prevent exposing others who aren’t immune. We might not have to wait until we have a vaccine to use immune individuals to reduce the spread of disease.”

Being able to reliably identify naturally immune patients is still a ways off, but Bellan and his fellow researchers hope that by studying the current outbreak and looking for asymptomatic individuals, they might be able to save lives in the future.