Are We Doomed To Arctic Winters In America?

Scientists Square Off On The Coming Freeze

There’s an unwelcome guest on your doorstep, America.

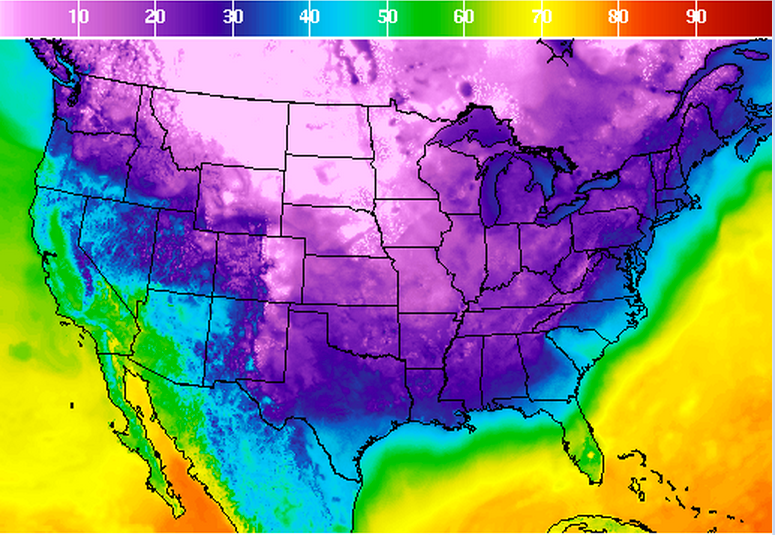

It comes from the north, dragging frigid air and awful commutes like a terrible shroud over the continental United States, from the Rocky Mountains all the way to the Atlantic. While the East Coast saw temperatures about 10 degrees below average Friday, snow hit much of the Midwest following a 40 degree drop over just a couple days in Chicago, and a region stretching from Denver to Montana saw sub-zero chills and record lows.

This morning, in the stairwell of an apartment building, even New York City’s relatively mild mid-30s weather prodded a father into a shouting match with his weeping child: “But I don’t want to go to school today! It’s too cold to go outside!” “Put your coat on, now!” And in the halls of climate research centers and weather stations across the nation, the cold snap is spurring a more technical, but no less divisive debate — one that matters to millions of Americans who remember the last awful winter: Is this the new normal?

Ice, Alaska, And Damned Typhoons

Pacific Blast

With nearly two weeks left before Thanksgiving, this should be a time for tweed and brisk walks through colorful fallen leaves (the autumn the Lands End catalog promised us). Instead, if you live anywhere from Chicago to Appalachia you’ve likely found yourself breaking out the Gore-Tex for a slog through accumulating snow and ice, with more likely coming this weekend, and its all because of a storm on the other side of the world.

Typhoon Nuri formed in the West Pacific and surged north, peaking with sustained winds around 180 miles per hour — one of the strongest typhoons or hurricanes of the year. As it moved past Japan and into the Arctic it weakened, but its powerful remnants still delivered tropical storm conditions to Alaska’s Aleutian Islands, Eastern Russia, and the Bering Strait.

You’d think a mega storm careening off into the underpopulated Arctic would be a kind of best-case scenario, and in many ways it is. There are fewer houses and people out in those cold places, and local damage was minimal. But those sparse communities share air with the jet stream (or “polar vortex”), a muscular current of air that circles counter-clockwise high in the atmosphere between the warmer air masses of the mid-latitudes and the much colder northern reaches.

Several scientists who disagree on most other issues surrounding polar vortex events (including whether “polar vortex” is an acceptable or ridiculous name for these Arctic air surges) came up with just about identical analogies for what happened when Nuri slammed into the jet stream: a taut rope snapping. All that frozen air normally locked in a tight spiral snapped south between an air pressure ridge over the Rockies and Greenland. The resulting arctic wave sunk temperatures far below average along the American continent, and they’ll likely remain low for a couple of weeks.

Polar America

Martin Hoerling, a scientist (and according to some of his colleagues, a contrarian) studying climate change with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), says fears of frozen winters future are fair but unfounded.

He says, “If I were a member of the public I’d be thinking, ‘Oh God, I barely survived the last winter and now it’s getting cold again? Is this what I can expect from now on?'” But Hoerling says this pattern of typhoon-induced cold fronts is not new, it’s just been given the new, scary, “polar vortex” branding.

If anything, he says, the warming world will see fewer extreme weather shifts because the Arctic and mid-latitudes will be nearer in temperature.

“If I were a member of the public I’d be thinking, ‘Oh God, I barely survived the last winter and now it’s getting cold again? Is this what I can expect from now on?'”

But Jennifer Francis, a researcher with the Institute of Marine and Coastal Sciences at Rutgers University who studies the impact of Arctic warming on the global climate, disagrees. Her research predicts that as Arctic warms (and it is warming extraordinarily quickly) the jet stream will weaken and narrow. “When you have a strong jet stream it’s like a thick rope. You can give one end a tug and not much happens.” But as it weakens, she says, it’s more like a string. A shake (or a typhoon) will send waves all along its length, causing the Arctic monster to move south more often.

While Hoerling dismisses Francis’s research as “pure conjecture”, and points to early failures to verify her predictions, other meteorologists and climatologists look at [several(http://www.nature.com/ncomms/2014/140902/ncomms5646/abs/ncomms5646.html/) recent studies and are more convinced.

James Overland, also of NOAA, says he leans toward Francis’s view. “In the last five years we’ve seen more of the wavy [jet stream] patterns in January and December than we did before,” he says. In his view, it makes sense that a warmed Arctic would break down the jet stream’s regular tight ellipse.

Francis acknowledges that her research does not fully account for everything that will impact this winter and those that follow. “All these are pieces to the puzzle,” she says.

The debate might seem academic, but its consequences go far beyond discomfort. Last year’s harsh winter cost the economy billions, and revealed just how unprepared much of the country is for even slight shifts in storm patterns. More winters like the last could mean more deaths, widespread damage, and economic sluggishness.

So, About January

All other things being equal, meteorologists expect a weak but warming El Niño effect to render this winter a relatively mild one, though forecasters have lowered the probability from 65 to 58 percent at last measure.

Hoerling, along with most other researchers, says there’s no reason to expect the current cold snap to portend a trend this season. But Francis isn’t so sure.

Last year’s harsh winter cost the economy billions, and revealed just how unprepared much of the country is for even slight shifts in storm patterns.

“It all depends on what happens with El Niño — if it does form, what we’re seeing right now will probably end,” she says. But she says it looks more and more likely that won’t happen. “The pattern of surface temperature in the North Pacific look a lot like last winter.”

In other words, let’s hope that unwelcome guest packs up and leaves for good. But if it comes back, bringing with it plunging mercury, snot-icicles, and general misery, you’d best be ready. Shiver