Could An Overactive Immune System Cause Schizophrenia?

New findings could help prevent the illness before it sets in

Though schizophrenia was first recognized more than a century ago, scientists are still not sure what causes it. In recent years, they’ve discovered more evidence that the immune system may be more involved in the presence of the disease than was previously thought. A new study, published online last week in the American Journal of Psychiatry, adds to it—the authors found that people with schizophrenia (and those at highest risk for the disease to set in) may have overactive immune systems working in their brains.

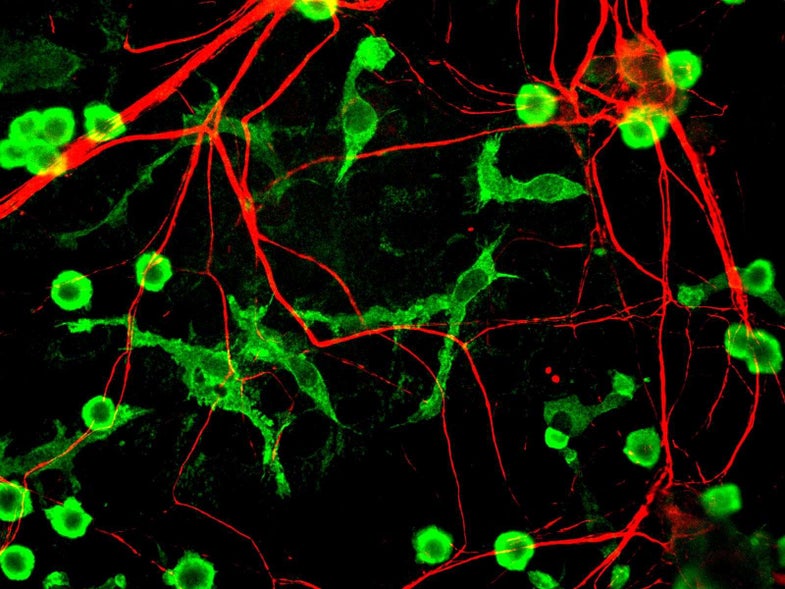

For the study, the researchers recruited 56 people, some of whom were healthy, and the rest had either been diagnosed with schizophrenia or were “at ultra high risk for psychosis,” the study authors write. They were interested in a particular kind of cell called microglia that protects the brain and central nervous system from pathogens that may attack it. To track the brain’s microglia activity, the researchers injected a type of radioactive biomarker that would stick to the cells and then show up in a brain scan.

The researchers found that people who had already been diagnosed with schizophrenia had much more microglia activity than did healthy people; those at highest risk of developing schizophrenia had much higher microglia activity, too.

Microglia activity, shown in PET scans of healthy, at risk, and schizophrenic patients

Since microglia also weed out unnecessary connections in the brain, the researchers hypothesize that the overactive microglia might be too overzealous, destroying connections that the brain needs so that it no longer functions properly, according to an article from BBC News. Given what we know about schizophrenia and about how the brain works, this might make sense—schizophrenia symptoms usually set in between ages 16 and 30, just around the time when the brain has finished its second big synaptic pruning that occurs during adolescence. And though it’s not yet clear why some patients have more microglial activity than others, previous studies of schizophrenic patients indicate that immune system dysfunction might be written into their genetic codes.

If other studies corroborate this finding, scientists might be able to stop schizophrenia before it sets in by treating the brain with anti-inflammatory agents to suppress the microglial activity. That solution wouldn’t necessarily address the genetic components of the disease, but it could provide relief for the 51 million people worldwide who are debilitated by the disease. But before more information is known, however, the researchers discourage patients from self-medicating with anti-inflammatory agents.