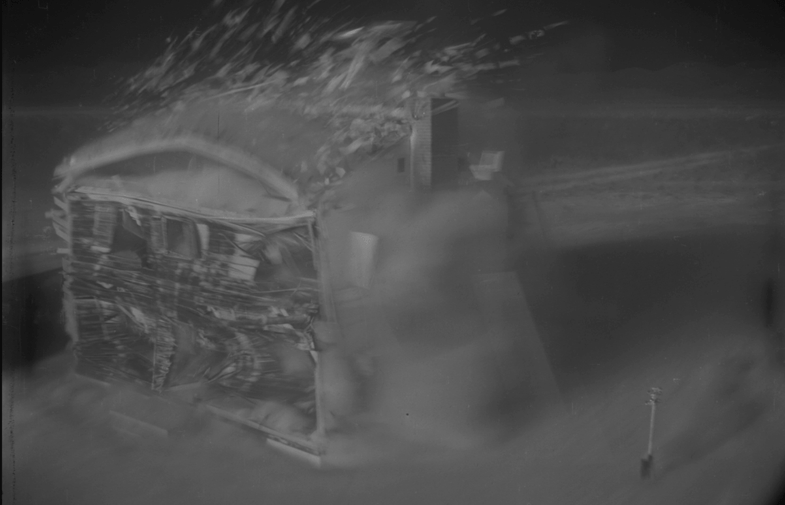

Watch a 1953 nuclear blast test disintegrate a house in high resolution

Footage may or may not contain a flying toilet.

On March 17th, 1953, a nuclear blast threw something out of the second story floor of a house built on the Nevada Proving Grounds. The test, dubbed “Annie”, was part of the larger Operation Upshot-Knothole, served two purposes: the military wanted to test new weapons, for possible inclusion in the United States’ arsenal, and Civil Defense wanted to learn what, exactly, a nuclear blast could do to a house. The lessons from these and other tests influenced decades of American nuclear posture, yet they left some questions unanswered.

Like: is that a toilet flying through the air, or what?

High-def nuclear house destruction — confirming w/ @NuclearAnthro that you can see the toilet (third shot, right of chimney) being expelled. pic.twitter.com/1HJmiq28dl

— Alex Wellerstein (@wellerstein) March 21, 2017

Researchers, like assistant professor Alex Wellerstein of the Stevens Institute of Technology, can only guess at what the object might be, while working within the limitations of the footage at the time. Wellerstein received this high-resolution footage from Los Alamos National laboratory in April 2016. Last week, Livermore National Laboratory put some declassified nuclear test footage online, which prompted Wellerstein to dig up the footage that might or might not show a toilet.

The object certainly seems toilet-shaped in some frames from the test footage, and appeared as such when Popular Science first wrote about the test in May 1953. But the mysterious object isn’t toilet-shaped in all frames from the test footage, and even with the high-resolution footage Los Alamos National Laboratory sent to Wellerstein, the nature of the specific object may in fact be unknowable.

Best e-mail of the day came from @bsdphk, arguing that it is NOT a toilet — made my day. (Reproduced with permission!) pic.twitter.com/eAAOxyk9t7

— Alex Wellerstein (@wellerstein) March 21, 2017

“How a second-story toilet fares in a nuclear attack” is a question that may only be answered after a nuclear armageddon, but there’s a surprising amount of mundane questions about survival in nuclear war that have answers.

The Civil Defense side of these 1953 tests were called Operation Doorstep, which was known as an effects test, where Civil Defense looked at the aftermath of nuclear blasts.

“The question was can you plan for a nuclear attack if you know for example that what kind of shelter would work best,” says Wellerstein. “Doorstep was meant to tell them information about civilian houses, so they want to know things like, if your house is a certain distance from where a nuclear weapon goes off, would you survive by being in the basement? Would you survive by being on the top floor? Would your chance of survival increase if you went to the basement when you’re on the top floor? What kind of variables matter?”

That focus on small home improvements to weather a deadly attack animated early coverage of fallout shelters, including at Popular Science, though as weapon sizes increased and arsenal grew into the thousands of warheads, the notion that nuclear war was survivable became more fantasy than public goal.

In 1953, that wasn’t the case. After all, the first nuclear weapon test occurred only eight years prior, and both weapons and arsenals were small enough that early nuclear war was theorized as deadly but not the end of civilization on earth as we know it. So Civil Defense planners took advantage of nuclear tests to plot life after the bombs fall, testing everything from dropping nukes on beer to how well file cabinets protect the papers inside in the event of a blast.

“There’s another report that I have that I really love basically asking the question of, will bureaucracy, the files and file cabinets, will they survive nuclear war or will you have a fresh start,” says Wellerstein, “and they conclude that the bureaucracy does fine. It turns out that a heavy filing cabinet inside a building is really survivable. The people, no, but the files will survive. And they did this by putting all these filing cabinets in the middle of the desert and nuking them.”

So what about the house? A house close to the blast is gone for sure, but the further from a blast the danger is more about heat. Wellerstein pointed me to a twelve-minute Civil Defense film called “House in the Middle,” about what variables make a house more or less likely to survive the heat from a nuclear attack.

“The real question is, if your house is dirty, does it increase the chances of it setting on fire?,” says Wellerstein, “Like if you’re a bad housekeeper with stuff stacked up in your living room, you know, crap in your yard, you haven’t updated the woodwork in your house, the shingles are falling off. The conclusion is that the house that isn’t upkept well is a much bigger fire hazard than the house that’s clean, has a 1950s sensibility about what the internal part of the house should look like. It’s basically about how you’re supposed to go and harass neighbors who have dirty, nasty yards, because they’re creating a nuclear fire threat for you because you live near them.”

This all seems like a dated, Cold War artifact, but there’s something visceral about seeing the house blown apart in high resolution. The way the fire climbs the house before the wood splinters, the dense clouds of smoke that block the camera, the possibility that a toilet or something roughly toilet-sized is hurled before this great messy fireball, it renews a grave sense of urgency to the whole nuclear enterprise. This was the lived reality that Civil Defense planners and early nuclear strategists prepared for, and Wellerstein cautions against dismissing it from the perspective of the present.

“It’s a really different world than the one we live in right now, we laugh and say ‘yeah, you’d be totally screwed, there’d be no way to ride that out,’” says Wellerstein, “and they’re like “well, we’re going to try our best anyway.”